Kamala Harris is Joe Biden’s history-making pick for vice president

Joe Biden has named his onetime rival Kamala Harris as his running mate, the campaign revealed Tuesday, elevating California’s junior senator as the first woman of color to appear on a major party’s presidential ticket.

Harris, who centered her unsuccessful White House bid last year on a promise to “prosecute the case” against President Trump, was widely seen as a front-runner to be Biden’s vice presidential pick. With her statewide experience as California attorney general and four years in the U.S. Senate, Harris was among the most conventionally qualified of the half-dozen or so women under consideration in the most diverse crop of contenders ever.

“I need someone working alongside me who is smart, tough, and ready to lead. Kamala is that person,” Biden wrote in an email to supporters Tuesday afternoon. The pair are scheduled to appear together for the first time as a presidential ticket in Wilmington, Del., on Wednesday.

In many ways, Harris, 55, is a safe pick — broadly popular in the Democratic Party and well acquainted with the rigors of a national campaign. But her selection also carries symbolic heft in this moment when race relations are at top of mind for voters, particularly since Harris, who is of Indian and Jamaican descent, had her own highly publicized confrontation with Biden over race during the primary.

“Joe Biden can unify the American people because he’s spent his life fighting for us. And as president, he’ll build an America that lives up to our ideals,” Harris tweeted. “I’m honored to join him as our party’s nominee for Vice President, and do what it takes to make him our Commander-in-Chief.”

Despite her strengths, Harris’ selection is not without risk, particularly if the race tightens. She was an inconsistent candidate in her own presidential run, and her record as a prosecutor has at times been a political millstone, particularly as attitudes on law enforcement and mass incarceration have dramatically shifted to the left. While Harris has more forcefully embraced criminal justice reform recently, she faces lingering distrust from some in the party’s progressive faction, including younger voters of color who did not broadly embrace her candidacy.

While the Trump campaign was quick to paint Harris as an out-of-touch liberal, the president himself appeared a bit subdued in reacting to the pick during a news conference Tuesday evening. He called her his “No. 1 one pick,” but added that he was surprised by her selection because “she did very, very poorly” in her presidential run and she had clashed with Biden during the primary.

His fiercest criticism centered on Harris’ grilling of Supreme Court Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh during his Senate confirmation hearing in 2018, one of several breakout moments she had as a new senator.

“She was the meanest, the most horrible, the most disrespectful of anybody in the U.S. Senate” during the hearings, Trump said.

Vice President Mike Pence, appearing at a campaign event at Mesa, Ariz., welcomed Harris to the race with a hint of sarcasm and boos from the crowd.

“As you all know, Joe Biden and the Democratic Party have been overtaken by the radical left,” he said. “So given their promises of higher taxes, open borders, socialized medicine, and abortion on demand, it’s no surprise that he chose Sen. Harris.”

Pence and Harris will meet on the debate stage on Oct. 7 in Salt Lake City.

Long considered a rising star in Democratic politics, Harris’ ascent to the presidential ticket has the potential to position her as a future leader of the party, particularly given that, should Biden be elected president, he would be 78 years old when sworn in. Biden, himself a former vice president, said his choice of a running mate would be a “simpatico” governing partner and someone ready to assume the Oval Office on “a moment’s notice.”

Covering Kamala Harris

“It’s overdue. It’s tremendous,” said Angela Rye, a Democratic political strategist and former executive director for the Congressional Black Caucus. “Kamala is not a stranger to making history, so it’s poetic justice that she’d be making history here.”

Rye, who had advocated for Biden to pick a Black woman, said the choice could also prove to be politically strategic by shoring up a constituency that is a must-win for Democrats, but often taken for granted.

A look at The Times’ coverage of Kamala Harris.

“Hopefully it signifies a tremendous shift in the Democratic Party by finally recognizing how important Black people, and most specifically Black women, are to the base,” she said. “We don’t just mobilize the Black community, but we mobilize the party overall.”

Despite the weeks of blustery speculation about Biden’s pick, the final decision was announced not by news leaks, but a text message to supporters. The campaign later tweeted a picture of Biden informing Harris via video chat on a laptop — an aptly socially distanced job offer in the era of coronavirus.

In making his decision, Biden consulted often with Democratic Rep. James E. Clyburn of South Carolina, the Black power broker whose endorsement turned the tide of the primary season irreversibly in Biden’s favor.

Clyburn said in a call with reporters he believed that the final three contenders were Harris, national security advisor Susan Rice and Los Angeles Rep. Karen Bass. But Biden was still talking with Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren as recently as this past weekend, a source familiar with the conversation said. He called Warren early this afternoon to let her know she had not been chosen.

Clyburn said he did not make a specific recommendation about whom Biden should pick. He did not believe the potential political liabilities of Harris’ record as a prosecutor should be a factor, he said.

“I told him I do not wish to see people’s professions held against them. You judge people by how they conduct themselves in their professions,” he said.

Once the pick was made official, Harris was celebrated by other women in contention for the job. Rice praised her as a “tenacious and trailblazing leader,” while Bass commended her “relentless advocacy for the people.”

They were echoed by a chorus of Democratic officials and interest groups signaling their approval, including former President Obama, who described the choice of a vice president as “the first important decision” a president makes.

“Joe Biden nailed this decision,” Obama said in a statement.

The war on drugs had erupted, apartheid was raging, Jesse Jackson would soon make the campus a staging ground for his inaugural presidential bid.

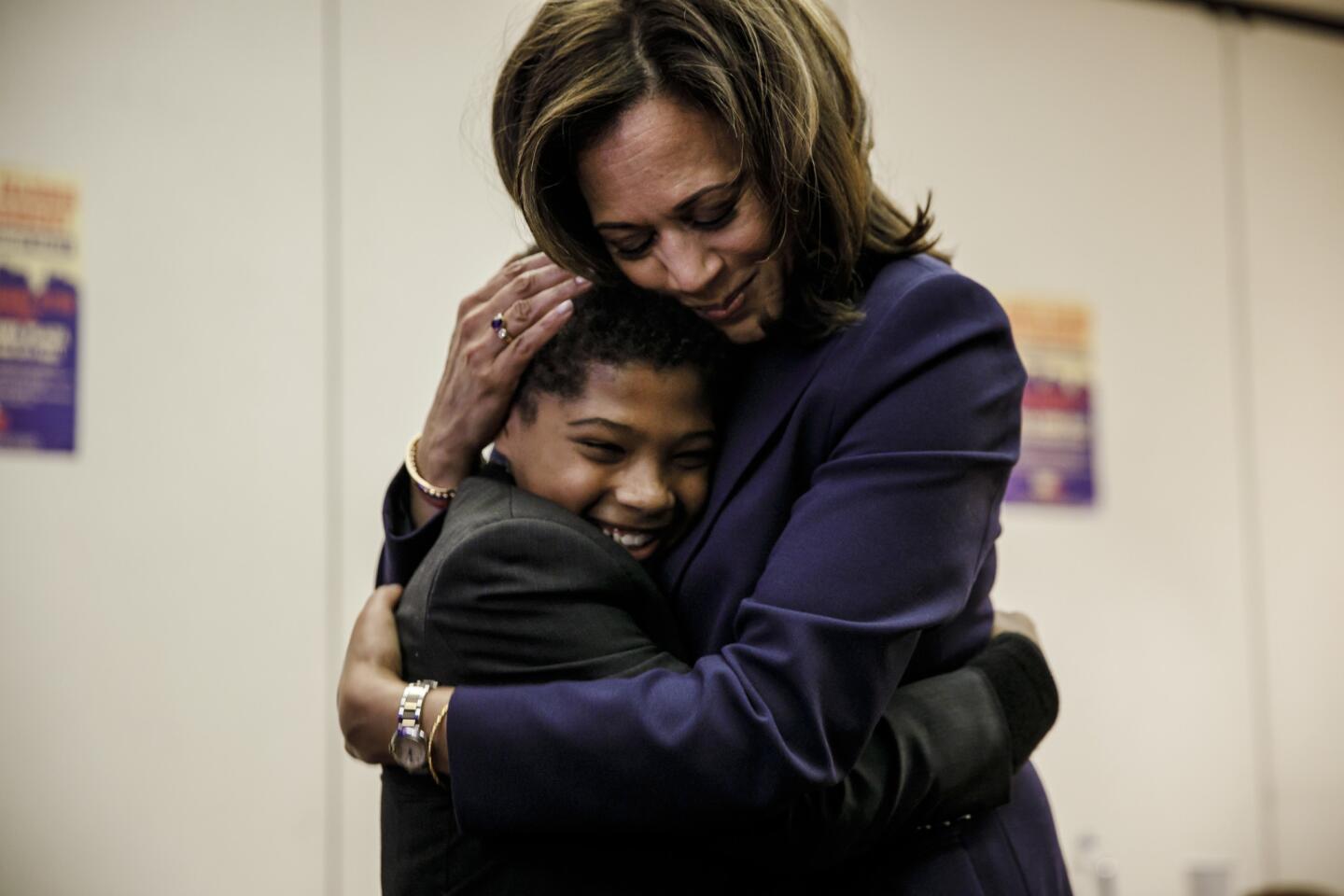

Born in Oakland and raised in Berkeley, Harris is the older daughter of two immigrants; her mother was an Indian-born breast cancer researcher and her father is an economist from Jamaica. She and her sister, Maya, who is one of Harris’ closest political advisors, were raised primarily by their mother, steeped in a hybrid of Indian and Black culture. She attended Howard University, a historically Black college in Washington, D.C.

Harris would often visit her mother’s family in India, usually Chennai, where her grandparents settled later in life. She was especially close with her grandfather, P.V. Gopalan, a civil servant, with whom she would make French toast and play five-card stud poker.

She is a product of the Bay Area’s competitive political training ground, having worked in the public sector her entire career. She now lives in Los Angeles with her husband, Douglas Emhoff, an attorney.

Harris spent 13 years as a prosecutor in Alameda County and San Francisco. She won her first elected office as San Francisco district attorney in 2003, and after two terms won a tight race to be California attorney general, a role she held through 2016.

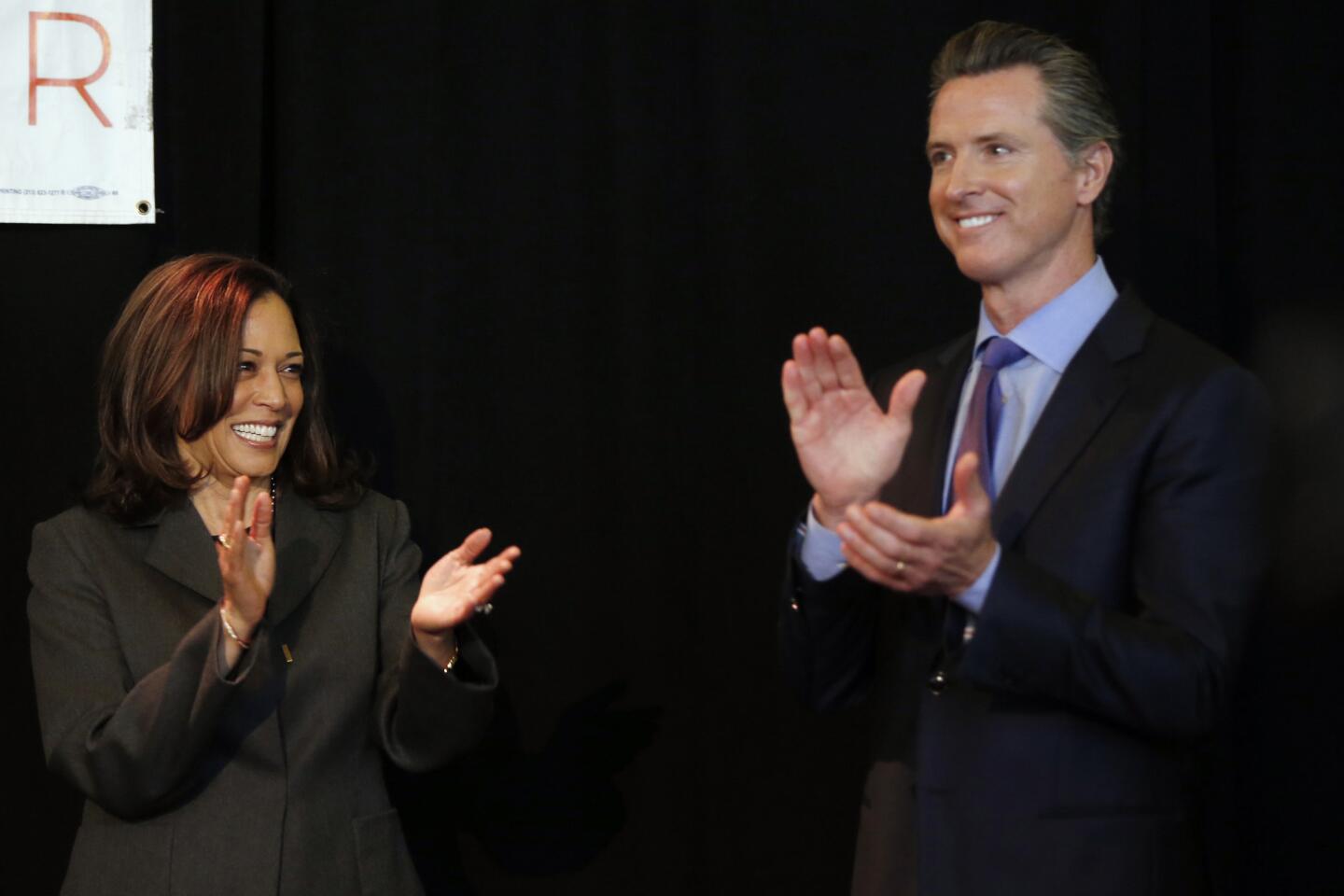

The appointment promises to be one of the most consequential of his political career, both in California and in regard to any ambitions he may have for White House.

Harris was barely two years into her first term as U.S. senator from California when she jumped into the presidential fray, buoyed by her high-profile prosecutorial interrogations of Trump administration officials in Senate hearings.

Her brisk grilling of then-Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions in 2017, for example, about his interactions with Russian officials during the presidential campaign a year earlier, left him tongue-tied and complaining that the pace of her questions made him “nervous.”

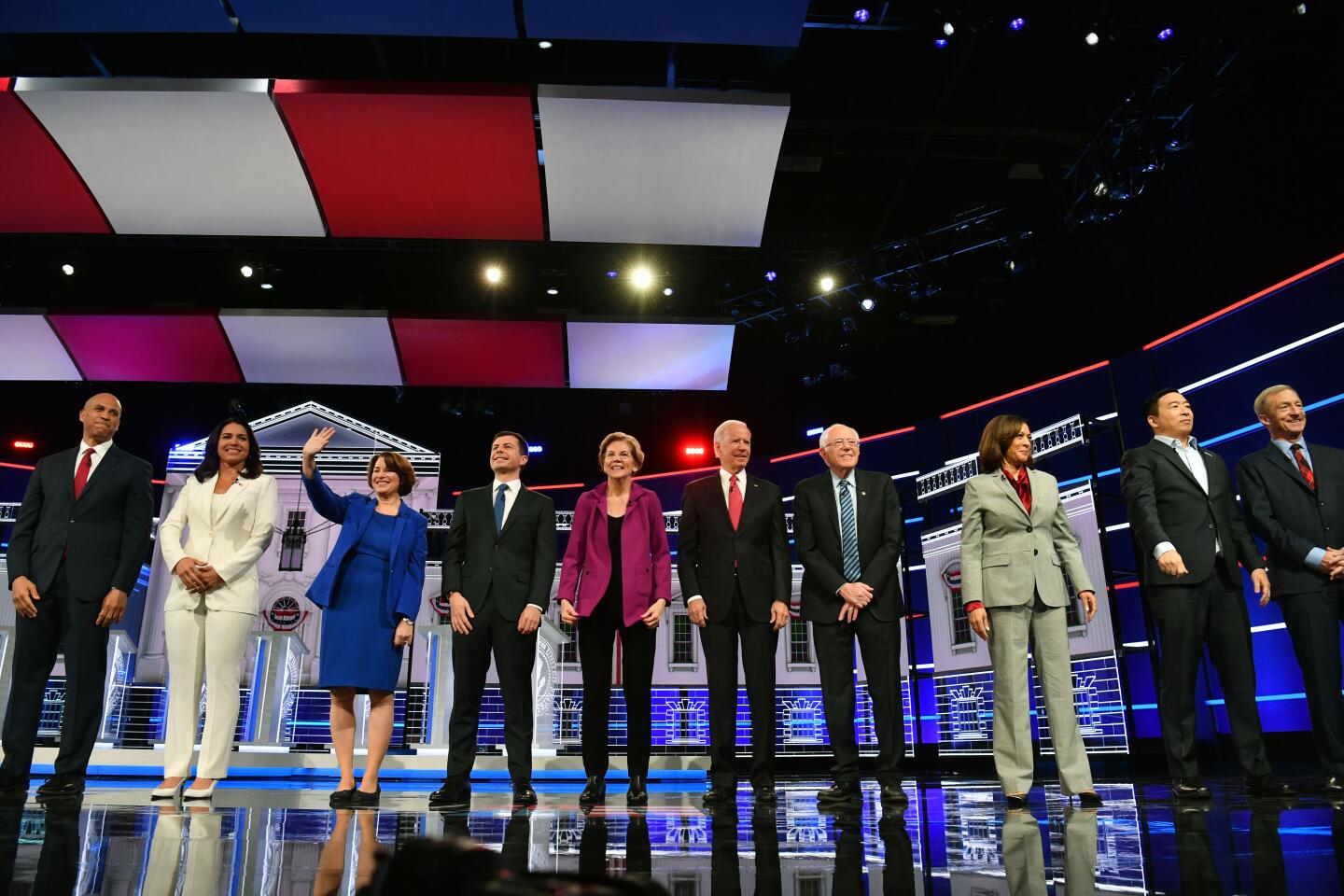

She immediately established herself as a top-tier candidate with a flashy Oakland launch rally in January 2019. But her campaign flagged in the spring as she struggled to square her law enforcement resume with a Democratic electorate that has lurched leftward on criminal justice issues.

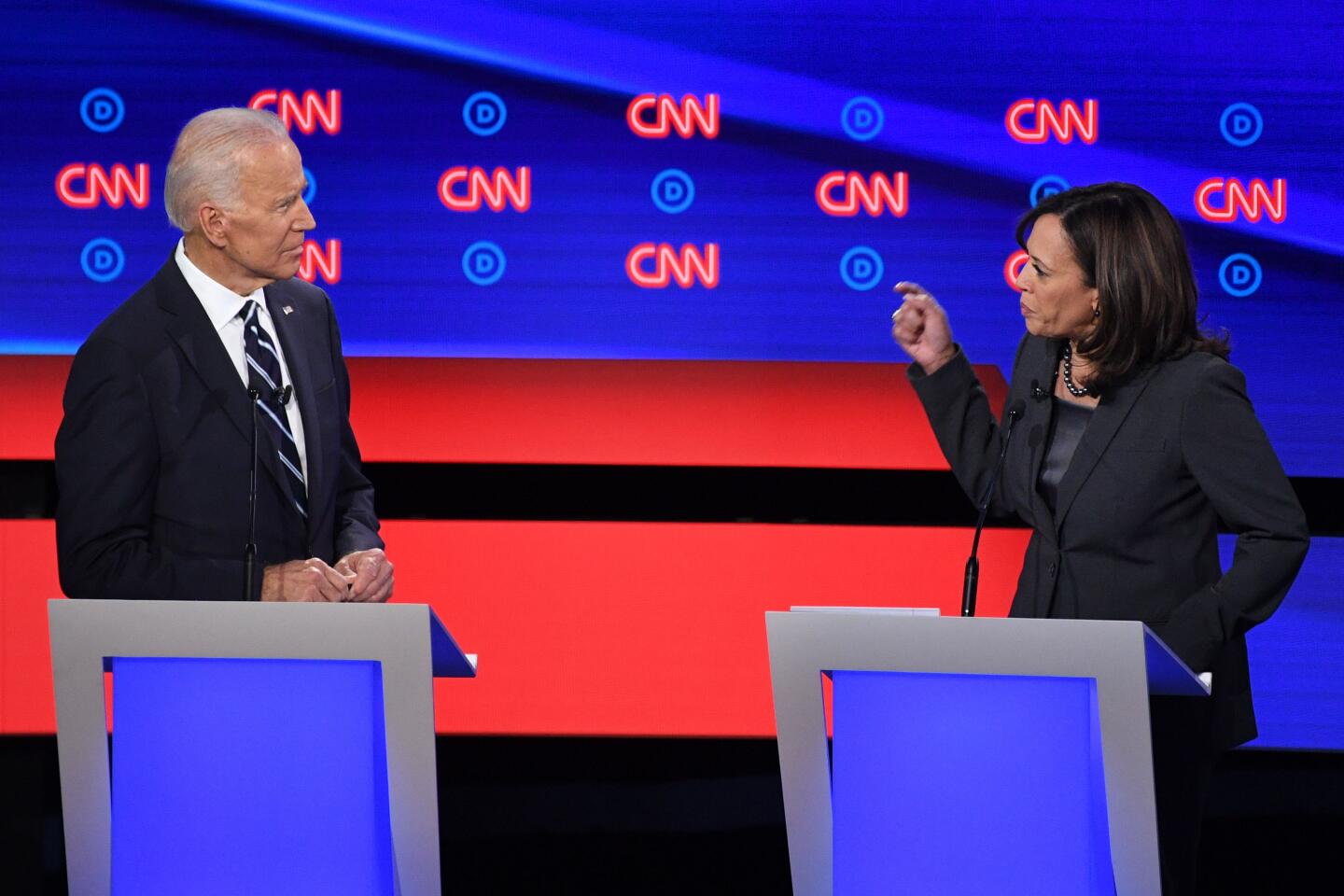

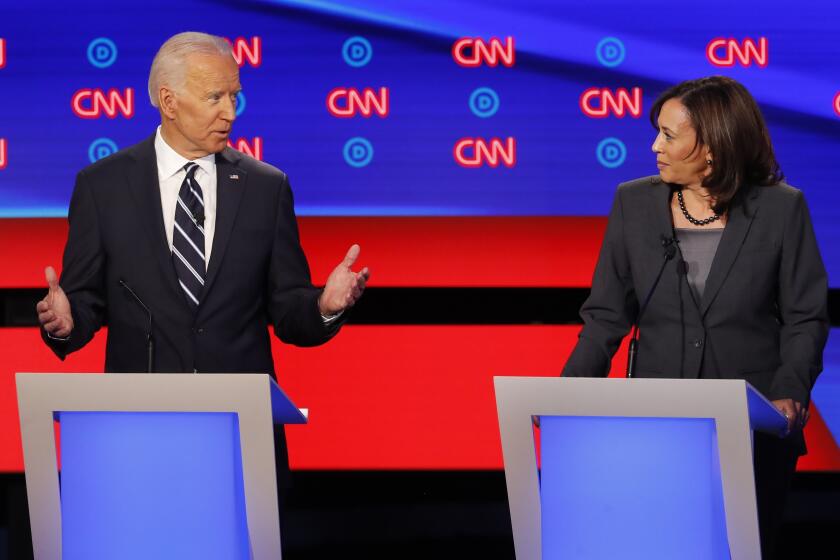

A defining moment of her presidential run came at the first Democratic primary debate, when she challenged Biden for speaking warmly of his collegiality with segregationist senators and his work with them to stymie busing to racially integrate schools.

“There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bused to school every day,” she said onstage, as she angled her body to speak directly to Biden. “And that little girl was me.”

Biden appeared flustered by the charge, particularly given his warm relationship with Harris, who had been close friends with his late son, Beau.

The confrontation had limited short-term benefit for Harris, whose campaign sputtered out under lagging poll numbers and dwindling fundraising by December, before any primary votes were cast.

California Sen. Kamala Harris addition to the 2020 Democratic presidential ticket is more than just symbolism. She’s unafraid to take on bullies.

Both Harris and Biden insisted that there were no lingering hard feelings. Harris, who endorsed Biden in March, has been an enthusiastic campaigner for the presumptive Democratic nominee, making frequent appearances at virtual roundtables and fundraisers.

It is not unheard of for once-fierce rivals to serve as running mates. In 1960, John F. Kennedy chose Lyndon B. Johnson for the Democratic ticket despite their mutual disdain. In 1980, Republican Ronald Reagan made George H.W. Bush his vice presidential pick even after Bush mocked Reagan’s policy agenda as “voodoo economics.”

Still, some Biden allies held the debate moment against Harris, arguing that the showdown undercut her ability to be a loyal running mate, particularly if she fixes her eye on succeeding him in the Oval Office (hardly an uncommon ambition for vice presidents).

Harris and Biden have departed on other policy matters, namely healthcare. Biden is a proponent of expanding the Affordable Care Act to include a public option. Harris backed a version of “Medicare for all,” although her shifting stances on whether private insurers should have a role in a government healthcare plan caused her some blowback during the primary.

With P.V. Gopalan, an upright civil servant and doting patriarch, Kamala Harris forged one of the defining relationships of her life.

At the time, Harris found herself on difficult ideological ground, wedged between centrists such as Biden and rivals to her left such as Warren and Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont.

Now, that position may offer the benefit of bridging the two wings of the party.

“Kamala is kind of in the territory between Biden and the truly progressives,” said Bruce Cain, professor of political science at Stanford University. “That can be a weakness for her, but it’s also a strength. There’s a certain ambiguity as to exactly how progressive she is.”

That has led to some disappointment on the party’s left flank. The Progressive Democrats of America and RootsAction, two grass-roots groups, dejectedly called Harris a “political weather vane” in a statement.

Others said the choice means the Democratic ticket will need to make continued overtures to progressives.

“Sen. Harris and Vice President Biden know that they have to reach all shades of blue within the Democratic Party, and there are existing rifts between Sen. Harris and some branches of the progressive family. I am convinced they are prepared to work through those issues in order to bring those voters to the table,” said Jane Kleeb, chairwoman of the Nebraska Democratic Party and a member of the board of Our Revolution, a political group allied with Sanders.

Harris also ends a decades-long political drought for California, the country’s most populous state, which has not been represented on a national ticket since President Reagan sought reelection in 1984.

Golden State politicians who have tried to make the leap to the White House since then, such as former Govs. Pete Wilson and Jerry Brown, “often had trouble translating their California experience nationwide,” Cain said.

“That’s not going to be a problem for Kamala,” he said, noting she went through nearly a year of national campaigning and five primary debates before dropping out of the race in December.

Times staff writers Janet Hook and Noah Bierman in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.