Column: Goodbye to traditional political conventions — and good riddance

Democrats around the country will gather around computer screens and smartphones next week for a strange new version of a timeworn political ritual: their party’s presidential convention.

They won’t flood into Milwaukee and crowd into a noisy sports arena on Aug. 17 for four nights of hoopla. They won’t hobnob with party elders, campaign donors or up-and-coming politicians. They won’t even wave placards or cheer, except in their living rooms.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made those traditions impossible — and the conventions will almost surely be better for it.

In a preelection report, the director of national intelligence’s office says Russia is actively trying to denigrate Joe Biden, China “prefers” that President Trump loses reelection, and Iran is seeking to undermine U.S. democracy.

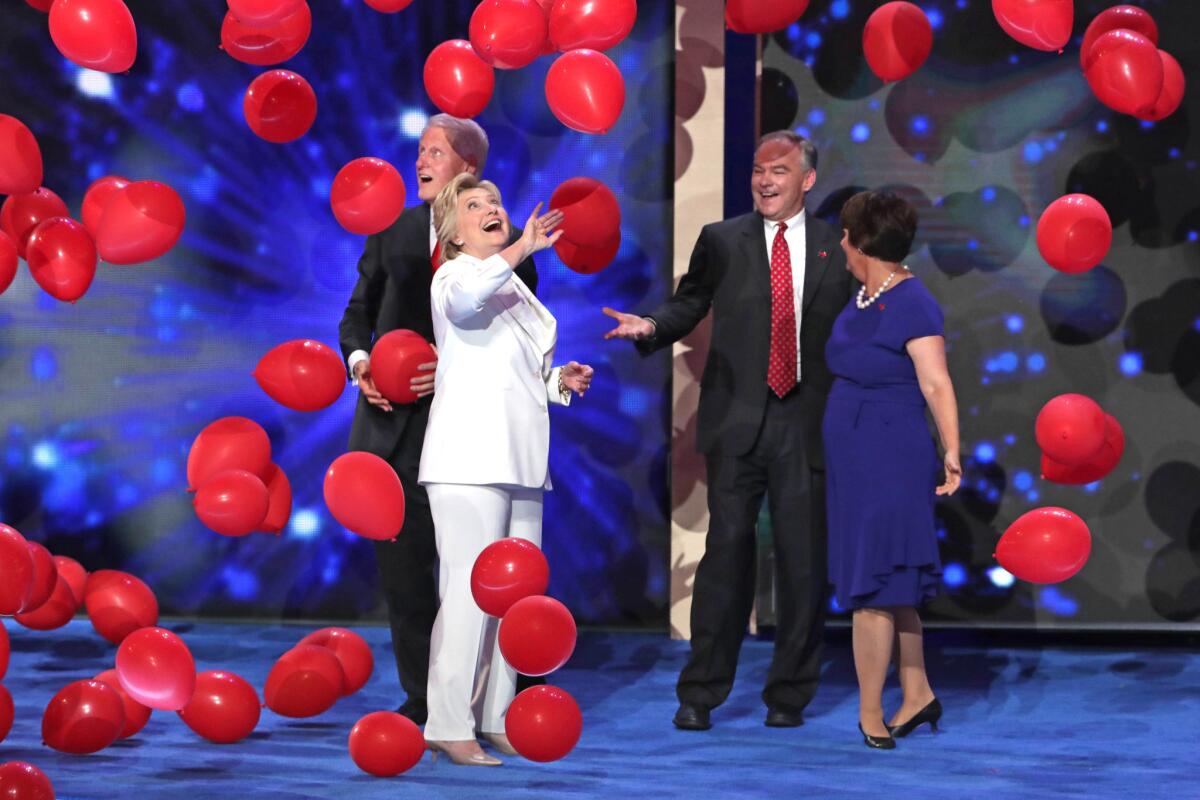

Ever since 1948, when convention proceedings were first broadcast on television, the quadrennial events have slowly morphed from authentic political gatherings into slickly produced infomercials.

This year, the conventions can finally be honest about what they are.

There will still be roll call votes, but they’ll only be for show; the nominees were chosen months ago. The last time a convention included a serious parliamentary battle was 1980, when Sen. Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts unsuccessfully tried to wrest delegates from President Jimmy Carter.

The old-style conventions weren’t particularly good TV; they were live pageants adapted for the small screen, often awkwardly. The live action — make that live inaction — got in the way.

This year, at last, that pretense can be dropped. There will be almost no live sessions, only speeches and video segments.

These will be television shows, pure and simple.

Instead of lame infomercials pretending to be conventions, they will openly and proudly be giant infomercials, a quintessentially American art form.

As a result, I expect they’ll be more watchable, and maybe even more informative, than when they were staged in sports arenas.

“They’re being designed to serve the viewers, not the delegates,” Chuck Todd, the political director of NBC News, told me. “That should make for better television.”

The change might even make the traditional set-piece speeches better, in the view of Kathleen Hall Jamieson, a political communication scholar and director at the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania.

“A speech written for television is different than one for a live audience,” she told me. “With a live audience, you write for applause lines; you want to draw cheers. A speech for television can actually invite more reflection from the audience.”

A made-for-video convention might even prompt broadcast and cable networks to scale back their habit of cutting away from speeches for analysis from pundits, she ventured.

That’s probably optimistic. Todd and other television planners said they’re largely adapting their traditional templates — live coverage of major speeches, with punditry in between — for the new format.

“My fear is that they’re going to give us a lot of difficult choices,” he said. “What’s the line between serving the viewer, including the viewer who may want to cheer for his or her team, and simply screening an infomercial?”

Making the infomercial so compelling that the networks want to keep it on the air is precisely what convention planners are aiming for.

Democratic strategists want their convention to reintroduce Joe Biden — his biography, his family tragedies, his government experience — to voters who have a blurry impression of him.

They will air a glossy biopic that emphasizes Biden’s time as vice president under Barack Obama and his image as the nation’s most empathetic politician.

They express confidence that Biden’s acceptance speech will dispel Trump’s allegations that the 77-year-old candidate is, as the president put it recently, “mentally shot” — an absurdly low bar he should clear without difficulty.

The online convention will feature a prime time appearance by Barack and Michelle Obama, and a tribute to the late Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.). Biden plans to give his acceptance speech from his home in Delaware.

That’s not only to protect Biden’s health; it’s to emphasize another Democratic theme, their insistence on following medical recommendations to reduce the spread of the coronavirus.

Republican plans appear less certain beyond an in-person meeting of delegates in Charlotte, N.C., on Aug. 24 to formally nominate President Trump.

Campaign officials say they will present granular details of Trump’s plans for a second term, attack “radical elements” that they claim control Biden’s team and present a “nightly surprise.”

Trump will deliver his acceptance speech on Aug. 27 — possibly from the White House, he said last week. But he might also drop in (digitally) on one or two other nights; he did that in person at his 2016 convention in Cleveland.

The Trump team is also working on a biopic recounting his first four years. It’s expected to argue that Trump’s leadership prevented the pandemic from getting worse and echo his promise that the economy will boom as soon as he’s reelected.

Both campaigns hope to produce a significant bounce in the polls that can serve as a springboard to victory on Nov. 3.

But like old-fashioned conventions, the bounce may be a thing of the past — probably because, in a polarized age, fewer voters appear willing to change their views. In the four presidential elections from 2004 to 2016, the average post-convention bounce was only 3%.

Delegates, donors, journalists and others who once flocked to conventions may mourn the loss of the spectacle, the noise, and the chance to mingle at receptions and meals.

But the vast majority of voters, who never got invited, won’t miss a thing.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.