Trump’s defiant help for Roger Stone adds to tumult in Washington

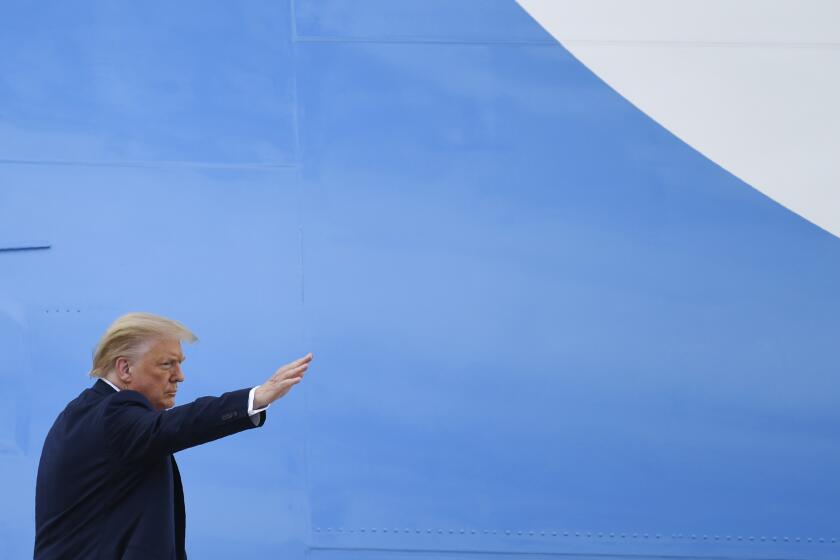

WASHINGTON — President Trump’s intervention in a criminal case connected to his own conduct drew fierce rebukes Saturday from Democrats and a few Republicans, with calls for investigations and legislation.

But it remained to be seen whether Trump’s most recent defiance of the conventions of his office to commute the 40-month prison sentence of political confidant Roger Stone, just four months before election day, would matter to voters grappling with a deadly COVID-19 surge and a national discourse on racial justice.

Shortly before heading out Saturday morning for his Virginia golf club, Trump made unfounded accusations against his political foes while taking another swipe at special counsel Robert S. Mueller III’s investigation, which led to felony convictions for six Trump aides or advisors, including Stone, a decades-long political character who embraces his reputation as a dirty trickster.

“Roger Stone was targeted by an illegal Witch Hunt that never should have taken place,” Trump wrote on Twitter. “It is the other side that are criminals, including Biden and Obama, who spied on my campaign — AND GOT CAUGHT!”

Trump has long sought vengeance against the Russia investigation that helped define his first two years in office. And now that his administration’s widely criticized response to the coronavirus outbreak has imperiled his reelection chances — with a battered economy and his poll numbers sliding — he has taken to testing the limits of his power in order to reward loyalty and fire up his base.

The decision to commute the sentence of the 67-year-old Stone — who was convicted of crimes including lying to Congress to protect the president and was due to report to prison Tuesday — was loudly celebrated by some in Trump’s orbit as a triumph over what they characterized as “deep state” prosecutorial overreach.

President Trump says he is ordering reexamination of the tax-exempt status of schools that provide “radical indoctrination” instead of education.

But the move announced Friday evening came over the advice of a number of the president’s senior advisors, who warned him it would be politically self-destructive to reward Stone, who was convicted of seven felony counts.

Trump had long floated the idea of clemency for Stone — as well as for other associates convicted of crimes, including his former national security advisor Michael Flynn and former campaign chairman Paul Manafort — which itself was viewed by some as witness tampering by encouraging them not to cooperate with prosecutors.

The reaction from Democrats was swift and furious.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) on Saturday called it “an act of staggering corruption,” saying legislation is needed to prevent a president from pardoning or commuting the sentence of someone who acted to shield that president from prosecution. House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam B. Schiff (D-Burbank) called it “offensive to the rule of law and principles of justice.”

And Trump’s Democratic challenger, Joe Biden, resurfaced a 2019 tweet in which he said that “Trump has surrounded himself with people who flout our laws — we shouldn’t be surprised that he thinks he is above the law.” Biden added: “Still true.”

Republicans largely stayed silent on the issue Saturday, reluctant again to challenge a president who remains very popular among rank-and-file GOP voters. But one loud voice was Utah Sen. Mitt Romney, who was also the lone GOP senator to vote to convict the president during his impeachment trial earlier this year.

“Unprecedented, historic corruption: an American president commutes the sentence of a person convicted by a jury of lying to shield that very president,” Romney tweeted Saturday.

Chief Justice Roberts sends a message that the Supreme Court is independent and not an ally of one party.

Sen. Patrick J. Toomey (R-Pa.) signaled dismay with the commutation, saying in a statement Saturday that it was a mistake, while calling the Russia investigation “badly flawed” and a source of “frustration.” He added that Stone had been duly convicted and that any objections to the conviction and trial “should be resolved through the appeals process.”

Republican Mark Sanford, the former South Carolina congressman who made a short-lived presidential primary challenge to Trump, wrote: “So much for the Republican Party being the party of law and order. Have we not lost our minds in not condemning as a party the president’s corruption by Roger Stone.”

But most Republicans who did speak out about the decision supported it. South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham, a Trump confidant, said Stone was convicted of a “nonviolent, first-time offense” and therefore the president was “justified” in commuting the sentence.

Advisors who had previously talked Trump out of acting on Stone’s behalf awaited the possible fallout, but they considered that Congress may be too consumed with coronavirus relief packages while wondering if the electorate long ago tuned out any talk of the complicated Russia investigation, particularly during a pandemic.

But Trump probably could not afford more political damage. He is decidedly trailing Biden in the polls, per his campaign’s own private admissions, and his effort to reboot his reelection bid took another blow when the campaigned called off his planned rally Saturday night in New Hampshire.

Campaign officials expressed deep worry about low turnout, as happened at Trump’s rally last month in Tulsa, Okla. Though an impending storm was blamed for the cancellation, sunny skies were seen in Portsmouth an hour before the president had been due to arrive.

Immanuel Jarvis, GOP chair in Durham, N.C., sees President Trump as a friend of Black Americans and the media as an enemy.

By commuting Stone’s sentence, Trump evoked other controversial acts of clemency by his predecessors, though his was done in the height of an election year.

President George H.W. Bush pardoned former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger on Christmas Eve 1992, six weeks after he was defeated for reelection, prompting an uproar from Democrats and the independent counsel investigating the Iran-Contra affair. And President Clinton waited until his final hours in office in 2001 to issue a raft of pardons, including of financier Marc Rich.

But one president who resisted the use of pardon was Richard Nixon, who privately discussed acts of clemency but never followed through even as many of his associates faced legal consequences related to the Watergate scandal.

A few months after resigning, Nixon himself received a pardon from his successor, Gerald Ford.

Stone, a former Nixon aide, told the Associated Press that he expressed his gratitude to Trump in a phone call.

“You know, he has a great sense of fairness,” Stone said. “We’ve been friends for many, many years, and he understands that I was targeted strictly for political reasons.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.