California lost in the race for coronavirus face masks. But it’s not alone

WASHINGTON — Desperate for face masks, California paid $800 million to a politically connected firm that failed to deliver most of the state’s order.

State officials in Mississippi paid nearly $500,000 to a company whose owner was convicted on federal fraud charges after he resold to grocery stores food that was intended for animals or meant to be destroyed.

The state of Georgia paid a company nearly $7 apiece for masks that normally cost less than half that.

As the novel coronavirus spread across the United States, the Trump administration left states and cities to fend for themselves amid shortages of key medical equipment. States and municipalities competed against each other — and the federal government — driving up prices and creating a chaotic every-man-for-himself environment.

The Times used public records requests to collect spending data from 20 states and large cities. They showed that amid the scramble to buy face masks, winners and losers emerged.

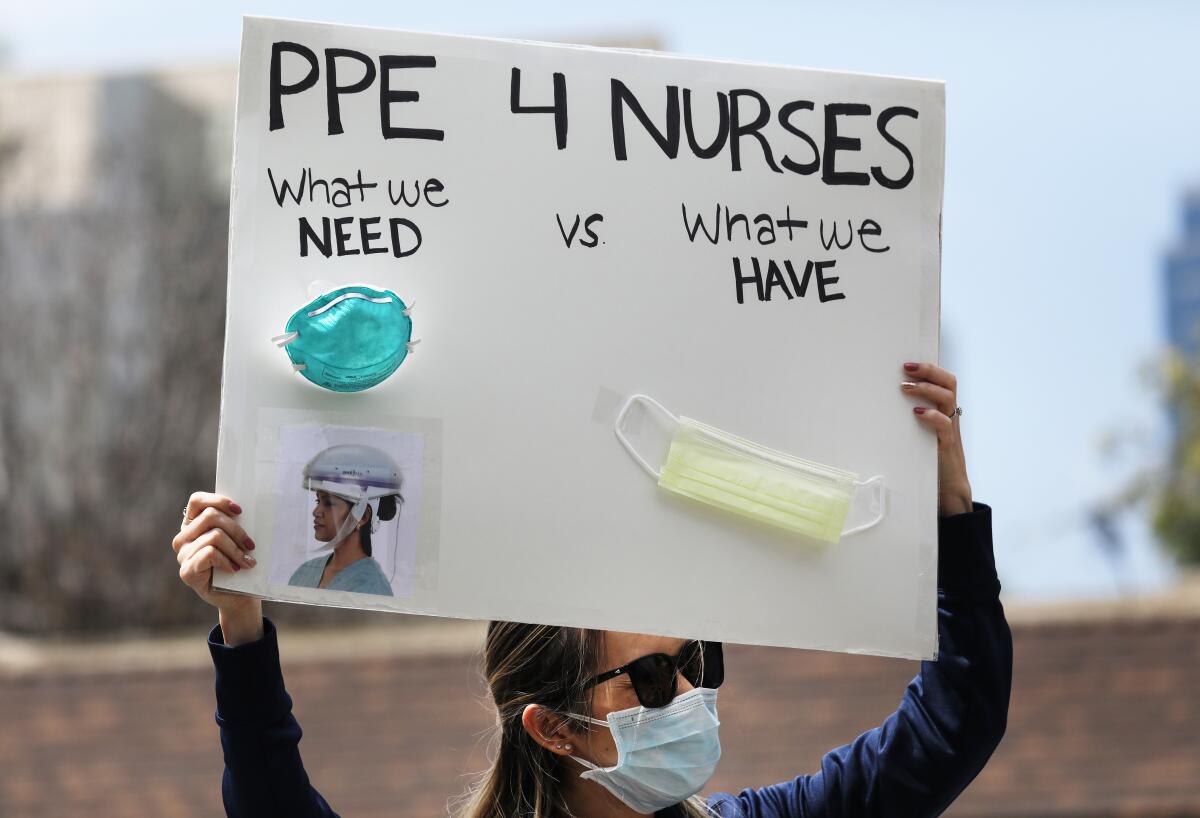

Large states and those that entered the market early, like Washington, got some of the best deals, paying fair rates for N95s — the most protective and coveted masks on the market. Smaller states and those that were slow to respond to the crisis found themselves on the outer fringes of the medical supply chain. With no choice but to abandon contracts and longtime suppliers, some of them paid exorbitant prices.

“It was brutal,” said Nick Vyas, executive director of the Marshall Center for Global Supply Chain Management at USC.

Large, well-funded states were mostly able to buy the protective gear they needed, Vyas said. But smaller states simply couldn’t compete. “They ended up having to pay more for supplies,” he said.

Supply chain experts fear these disparities could continue as businesses reopen and virus transmission rates rise in more than 20 states.

In Mississippi, the urgency to buy face masks led the state to do business with a contractor who had pleaded guilty to federal fraud charges.

The state placed multiple orders for masks with Silver Dollar Sales, a grocery outlet owned by Randy Sparks, who in 2018 admitted to participating in a conspiracy to resell food products that were supposed to be used as animal feed or for agricultural purposes. According to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Washington, the scheme had involved producing fraudulent paperwork.

Still, purchasing records show that Mississippi officials agreed to buy more than 91,000 KN95 masks — a Chinese standard similar to N95 — from Sparks for $6.50 each. It was more than double what many other states paid for similar masks.

Mississippi finance records show that the state paid $466,982 to Silver Dollar Sales. It’s unclear how many masks Sparks ultimately delivered.

When reached by phone, Sparks declined to comment and referred questions to Mississippi’s Emergency Management Agency. Gregory Michel, the agency’s executive director, declined to be interviewed by The Times and did not respond to written questions.

The state’s deal with Silver Dollar Sales was not an anomaly. Across multiple transactions with other companies, Mississippi officials agreed to pay inflated prices for relatively small orders of KN95 masks.

“In a crisis, you’re trying to balance cost, quality and timing,” said Trevor Brown, a professor of public management at Ohio State University. “In this case, I would imagine, timing prevailed.”

Brown said states and cities where coronavirus outbreaks emerged after heavyweights like California and New York had entered the market were at a distinct disadvantage. The domestic market had been picked clean. And while large states and the federal government were buying masks from China in the millions, smaller ones struggled to get sellers’ attention.

In mid-March, as governors pleaded for federal intervention to help them buy lifesaving medical supplies, Trump announced that the federal government was “not a shipping clerk.” States and cities would have to purchase their protective gear — and they’d have to do it without the president mobilizing industry to increase production.

The conditions were perfect for a frenzied gray market.

Unprepared and inexperienced at buying vast quantities of medical supplies, many states initially turned to contracted vendors, only to find that those distributors were already stretched thin and struggling to restock.

Solicitations poured in from brokers claiming to have connections in China, where they could secure shipments of N95 or KN95 masks. Citing the public health emergency, many states dispatched with their competitive bidding requirements and turned to vendors they’d never worked with before.

Steven Haynes, an entrepreneur in Dallas who got into the protective gear market at the beginning of the outbreak, said New York and California drove up prices for everyone else.

“New York in particular — they just bought everything — and they couldn’t care how much they paid,” said Haynes, who has sold masks to three other states. “They needed it. They were the center. But then nobody wanted to sell below the New York benchmark.”

In Houston, city officials tried to get around this problem by bundling their orders with nearby cities, counties and medical centers, hoping to get the attention of a proven supplier. Still, they found that companies like 3M and Honeywell were focused on states ordering hundreds of millions of masks.

Jerry Adams, Houston’s chief procurement officer, said the city wound up buying N95 masks from doctors’ and dentists’ offices that had closed during the pandemic.

When a local real estate developer and entrepreneur approached the city, offering 10,000 KN95 masks for $5.50 apiece, Adams knew the price was high. He said the market was pushing smaller buyers like him to what he considered a less protective product, at a price larger buyers were paying for the gold standard: N95s. But he agreed to pay.

“At that time, we had no N95s anywhere close to being delivered,” Adams said.

Since then, the city has acquired about 18,000, but most of its mask orders still have not arrived.

Some states that were early to the market got the best deals.

State purchasing records show that Washington, where the virus first established a deadly toehold in America, worked with sellers offering millions of N95 face masks for $3 or less.

When other states jumped into the mask market weeks later, prices had doubled.

The possibility of a second viral wave this fall has led some researchers to study ways states and cities might avoid the price gouging, fraud and failed deliveries that affected whether many Americans received adequate protection in the early days of the outbreak.

Academics at USC are working on ways states and municipalities might band together on future orders to lower their costs. Vyas, the supply chain expert, said the university is planning to share lists of proven contractors with states.

Rich Tong, a Seattle-based former Microsoft executive, and Sandra Archibald, former dean of the University of Washington’s Evans School of Public Policy and Governance, are also trying to help states buy protective gear wisely.

Through their nonprofit Restart Partners, they are introducing states and cities to a model Tong created that projects how many masks, gloves and other supplies governments should stock during the pandemic. Equipped with more information to plan their purchases, Archibald said, states could avoid paying high shipping costs for expedited delivery.

As manufacturing ramps up in the U.S. and shipments from overseas arrive, state officials said they are seeing mask prices drop. But they are nervous costs could skyrocket again in the fall.

At the outbreak of the virus, “everybody got caught flat-footed,” Adams said. Now he’s trying to be better prepared, with more supplies stockpiled than before.

“What I’d like to know,” he said, “is what is the second wave going to look like?”

Times staff writer Jie Jenny Zou contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.