Trump response to George Floyd’s killing makes U.S. diplomats’ jobs harder

WASHINGTON — For U.S. diplomats around the world, these are dispiriting times.

Entrusted with duties that include extolling democratic values in scores of developing and autocratic countries, career foreign service officers are finding their mission undermined by events back home.

The police killing of George Floyd, an unarmed, handcuffed black man, and the unprecedented law enforcement crackdown that followed — including the temporary prepositioning of active-duty troops, deployment of the National Guard and use of a low-flying helicopter against protesters in the nation’s capital — has strained the United States’ moral authority when it comes to serving as a model for other nations.

“It’s absolutely tough to be a diplomat out in the field right now,” said Barbara Leaf, former U.S. ambassador to the United Arab Emirates who served under both President Obama and President Trump.

Many diplomats say they don’t mind facing criticism about racism in the U.S. because it can open the door to frank discussions with other governments about the need to confront it, including in the United States.

But Trump’s threat to unleash the military to “dominate” protestors, Defense Secretary Mark Esper’s characterization of Washington, D.C.’s streets as a “battlespace,” and the deployment of numerous mysterious, unidentified security agents to confront demonstrators conjured images more often associated with authoritarian regimes — the kinds of things American diplomats usually condemn.

The Floyd killing and the subsequent protests pose a particular challenge to U.S. credibility in Africa.

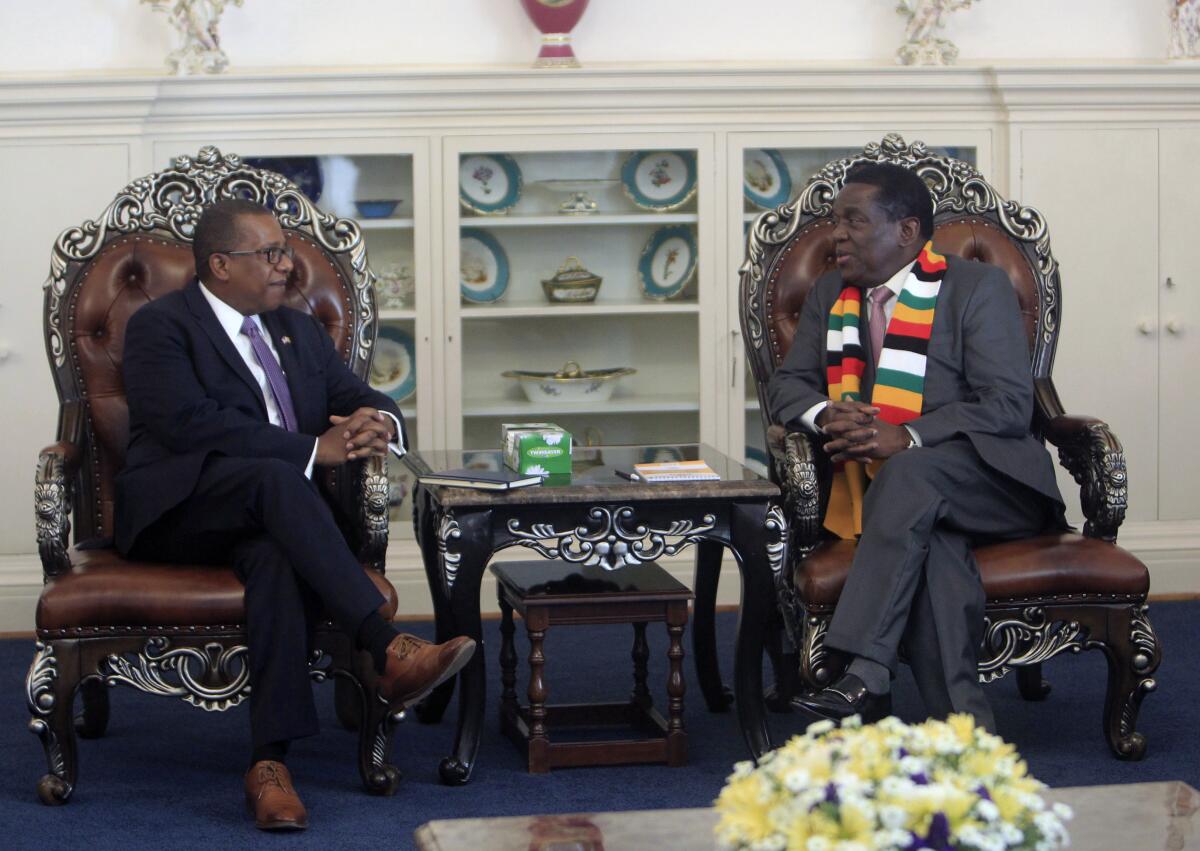

Brian A. Nichols, the U.S. ambassador to Zimbabwe, had the awkward mission of meeting with that country’s foreign minister, S.B. Moyo, to demand his government “end state-sponsored violence against peaceful protesters” just days after Floyd’s death and hours before Trump had peaceful protesters violently ejected from Lafayette Square, across from the White House, so he could stage a photo op.

Nichols attempted to navigate the delicate situation by acknowledging that Black Americans, like Zimbabweans, struggle for their rights. “Americans will continue to speak out for justice, whether at home or abroad,” Nichols told Moyo, according to a statement the U.S. embassy released.

But Zimbabwe government officials — who are rarely receptive to U.S. advice anyway — were particularly dismissive. The country’s defense minister said with contempt that the pressure was coming from a country that kills Black people “willy nilly. ... This is America for you.”

Stephanie S. Sullivan, a career foreign service officer who currently serves as ambassador to Ghana, joined many U.S. missions in Africa in quickly condemning the killing of Floyd by a white Minneapolis police officer. She said his death “is prompting important and necessary conversations in the United States, and serves as a reminder of the importance of confronting painful truths head on.” She added that “we can do better” in “addressing the underlying conditions and existing systems that perpetuate racial injustice” in the United States.

Asked by reporters if the events in the U.S. had any impact on his work as special envoy for Syria, veteran diplomat James Jeffrey said no. But he added: “I’m not here to comment on the situation in the United States, but the right of assembly is a Bill of Rights right in America. We do it in America. We urge other countries to do it.”

Other diplomats say the administration’s handling of the protests has not harmed U.S. standing abroad.

Kelly Craft, a major Republican donor from Kentucky who was named U.S. ambassador to the United Nations last year, told reporters last week that she has been impressed by the number of countries represented on the U.N. Security Council who have “reached out in support of the fact that the U.S. is allowing the freedom of speech.”

She said she sees no contradiction between what the U.S. advocates abroad and how the U.S. protests were handled at home.

“We have to remember that there is no moral equivalence between our free society and other societies,” Craft said.

But reaction from governments and groups who most frequently find themselves at the end of pointed U.S. barbs regarding human rights and violence has been predictable and swift.

“The heavy-handed crackdown reveals in broad daylight Washington’s double standard on human rights,” the official Chinese news agency Xinhua said. “The United States has an infamous track record of boasting and exporting its so-called ‘universal values’ around the globe, oftentimes interfering in the internal affairs of sovereign nations.”

Russia told the U.S. to “look in the mirror” and drop the holier-than-thou attitude. “The United States simply cannot have any questions for others in the coming years,” the foreign ministry spokeswoman, Maria Zakharova, said in Moscow.

Palestinians and their supporters say the U.S. appears to be adopting many of the harsh law enforcement tactics that Israel has used for years in the occupied West Bank and Gaza, further eroding U.S. credibility to act as a mediator in the Mideast conflict.

Diana Buttu, a lawyer and former advisor to the Palestinian Authority, said the images from the U.S. “are triggering really awful memories” from when she has been caught in similar Palestinian-Israeli skirmishes. She said it suggested that U.S. security forces, like their Israeli counterparts, “see everything through the lens of security, not rights.”

And Venezuela’s socialist president, Nicolas Maduro, whom Washington has been trying to overthrow for a year and a half with crippling economic sanctions, said the police brutality and racism disqualified the U.S. for making any demands.

“They want to suffocate us the way they suffocated this young African American,” Maduro said in a television address.

Even some democratic allies have raised concerns. Australia is investigating why an Australian TV crew was roughed up by police near the White House. British parliamentarians said they wanted to stop selling lethal equipment to the United States.

That has made sticking to the narrative of the moral authority of the United States more difficult, diplomats say.

“As American diplomats, it is our job to explain America to the world,” Eric Rubin, former ambassador to Bulgaria who is president of the union representing foreign service officers, told his members last week. “We have always pointed to our story as being worthy of emulation. ... This week, we have been forcefully reminded that we still have a long way to go as a nation.” A career foreign service officer, Rubin was nominated to the Bulgaria post by Obama and left it last year.

The events have created a dilemma for some ambassadors and top diplomats who work at the pleasure of the president and are expected to support administration policies.

“We have to color within the lines and are limited to what we can say about whether the administration is breaching” U.S. norms, Leaf said in an interview. “We can talk about the causal principles behind all the unrest, the [Floyd killing] … all the larger issues of justice. But can a serving diplomat speak about the administration’s response? No.”

More than 500 former diplomats and military officers did, however. They signed a petition condemning the use of military assets to “intimidate” and otherwise break up peaceful protesters, noting that America’s strict separation of the U.S. military from politics is an inspiration and model for those in repressive societies seeking greater freedom.

“Misuse of the military for political purposes would weaken the fabric of our democracy, denigrate those who serve in uniform to protect and defend the Constitution, and undermine our nation’s strength abroad,” the document says.

Roberta Jacobson, a former assistant secretary of State and the U.S. ambassador to Mexico until mid-2018, said confronting chronic problems such as corruption and civil rights abuse has been made more difficult since the start of the Trump administration.

“It’s so difficult to say, ‘Do as I say, not as a do,’” she said in an interview. “I don’t know how you advance democracy and human rights as a moral example anymore. That is sad, debilitating and draining.”

Indeed, American diplomacy was already reeling from challenges under the Trump administration, which has shown little interest in traditional detente, international relations and multilateral work. Trump’s “America first” doctrine has alienated allies, turned a blind eye to the misdeeds of many adversaries and diminished U.S. credibility and influence on the world stage.

Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo condemned the Floyd killing, but endorsed the law enforcement response. His work has not gotten any easier, either.

In recent days, Pompeo has attempted to focus international attention on China’s crackdown in Hong Kong, a potentially irreversible power play by Beijing. But his efforts have been overshadowed — by the similar scenes playing out in American cities.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.