Trump’s response to the coronavirus disaster causes trouble for his campaign

Toledo, IOWA — The danger of the coronavirus pandemic has become very real for LeAnn Davis. A major outbreak at a National Beef plant near this Iowa town of 2,100 has left one of her friends hospitalized.

Davis is put off by President Trump’s refusal to wear a face mask and alarmed by his rush to reopen the economy.

“It’s too soon,” she said. “It’s way too soon.”

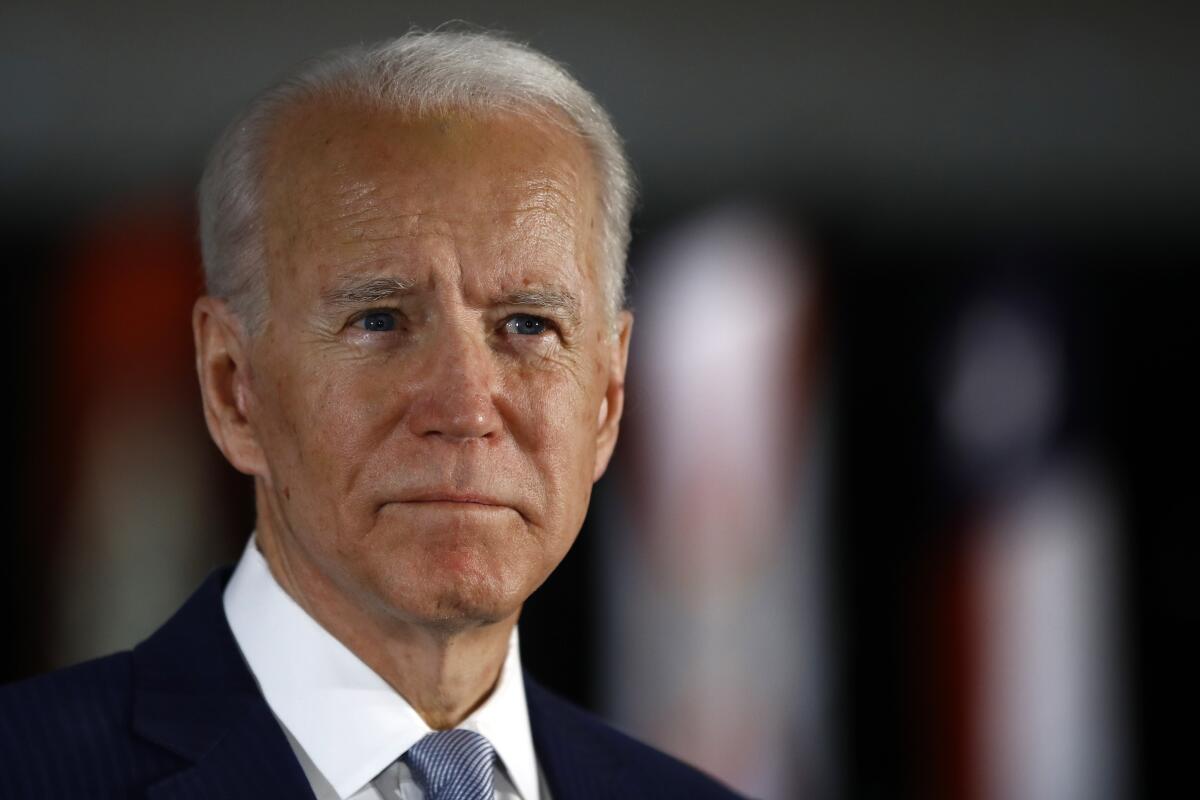

Trump has begun pouring money into television advertising in Iowa, a state that he easily carried in 2016, and voters like Davis are a big part of the reason. The 50-year-old Democrat voted twice for Barack Obama, then skipped the 2016 election because she didn’t like Trump and didn’t trust Hillary Clinton. But this time, she’s voting for Joe Biden.

If enough voters like her — dissatisfied with Trump’s leadership in a health and economic catastrophe — turn out for Biden, the president’s dominance in Iowa is in jeopardy.

Trump’s campaign has spent more than $400,000 to run television ads in Des Moines, Cedar Rapids and Sioux City in recent weeks, according to Advertising Analytics, an ad tracking firm.

The spots frame the 73-year-old president’s response to the coronavirus as tough, quick and “not always polite” and portray the 77-year-old Biden as an addled old man with a history of coddling China.

As a mainly white farm state, Iowa should be safe territory for Trump, whose political base includes rural America. He beat Clinton by more than 9 percentage points here. But with the coronavirus upending life for Iowa’s 3.2 million residents, the state no longer looks like a sure bet.

“If you’re advertising in the state, it’s competitive — period,” said Ken Goldstein, a politics professor at the University of San Francisco.

The Trump campaign is also spending more than $600,000 on TV commercials that started airing Thursday in Ohio. Like Iowa, it’s a state the president won handily in 2016; he beat Clinton by 8 percentage points. It’s highly unlikely Trump can win the Electoral College without victories in both states.

Trump’s spending is enough for his ads to be seen by most Iowa and Ohio TV viewers. It stands out from his otherwise unsurprising ad buys recently in the six states widely seen as up for grabs: Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Florida, Arizona and North Carolina.

At a time when Trump could be expanding the battleground map to states that Clinton narrowly won, such as New Hampshire, Minnesota or Nevada, he instead is shoring up support in states that should be part of his base.

“The bottom line is this guy is having to advertise in a bunch of places he shouldn’t have to advertise,” said David Doak, a Democratic consultant who has made ads for candidates across the nation.

Toss-up contests from Arizona to Florida hold the key for President Trump and Joe Biden.

Tim Murtaugh, the Trump campaign’s communications director, described the Iowa and Ohio advertising as routine efforts to keep supporters engaged “even in states where we have a high confidence in winning.” He also recalled Clinton’s failure to devote campaign resources to Michigan and Wisconsin, states she lost by tiny margins.

“We take nothing for granted, unlike Hillary Clinton in 2016,” Murtaugh said. “We are not making that mistake.”

Polls have found most Americans disapprove of how the president has handled the coronavirus crisis, with elderly voters — a source of strength for Trump in 2016 — especially turned off.

“This push to reopen and the dismissive attitude that he seems to have toward the death and suffering this is causing, I think it bothers a lot of people, especially some of the more vulnerable,” said Alan Abramowitz, a political scientist at Emory University in Atlanta.

In Iowa, the impact of COVID-19 is severe, with more than 19,000 confirmed cases and 535 deaths. Here in Tama County, where 27 have died, fatalities per capita are the highest of Iowa’s 99 counties.

Meatpacking plants are a major source of infection. Iowa processes one-quarter of the nation’s pork — or 155,000 pigs per day. Outbreaks at Iowa’s pork and beef plants have triggered supply disruptions that will cost the industry $2.7 billion as shutdowns force farmers to euthanize herds, said Gov. Kim Reynolds.

It’s the pandemic that grounds Davis’ opposition to Trump.

“He’s self-centered,” she said, pointing to the president’s refusal to wear a face mask. “And he’s not too keen on learning about anything that’s going on around him.”

Sandy Mullin, a waitress at Toledo’s Flaming Office Bar & Grill, has also been touched by COVID-19. Her 90-year-old aunt is recovering from the virus, and a friend who worked at the National Beef plant caught it, too.

She, too, voted for Obama, then declined to cast a ballot in 2016 because she loathed both Clinton and Trump. She hasn’t decided whether to back Biden, but is dead set against Trump. She shook her head as she talked about Trump bringing up bleach injections to fight the virus.

“For someone who’s supposed to be leading this country, some of the things he says,” she said, trailing off.

It’s not just the pandemic putting Iowa into play. Trump also lacks a key advantage he held in 2016: Clinton, who was viscerally disliked by many rural and small-town voters, is not on the ballot this time. Her vote share in Iowa’s presidential election was the lowest of any Democratic nominee since 1980. Even among Democrats, Clinton had trouble in Iowa: In the 2016 party caucuses, she beat Bernie Sanders by just a fraction of a percentage point.

Former Vice President Biden has wider appeal.

“Biden is seen as Uncle Joe,” said Doug Gross, a Des Moines attorney and Republican fundraiser who believes Biden is strong among moderates in Iowa. “That’s a danger for the president.”

Iowa’s recent history suggests Trump has good reason to advertise in the state.

Republican George W. Bush lost Iowa in 2000, then won it four years later — in both cases by less than 1 percentage point. Obama won the state decisively in 2008 and 2012.

The state swung strongly toward Democrats again in the 2018 midterm backlash against Trump’s tumultuous presidency; Democrats ousted two Republican congressmen and now hold three of the state’s four House seats.

David Kochel, an Iowa Republican strategist and Trump critic, said the same kind of suburban revolt against Trump that fueled the Democratic takeover of the House in 2018 poses risks for the president’s reelection, so he will need to maximize turnout in conservative rural areas. Trump remains the favorite in Iowa, he said, but Biden is a formidable opponent.

Even before the pandemic, it was unclear whether most farmers in Iowa and other agricultural states would stick by Trump as his trade war with China cut exports and the president doled out subsidies to make up for the shortfall.

Gross, the Republican fundraiser who was chief of staff to former Gov. Terry Branstad, sees Iowa as more competitive than many outsiders realize.

“From the trade war, you go into a pandemic shutting everything down. We’ve got farmers in Iowa more reliant on government assistance than they’ve ever been,” Gross said. “That’s where the president has some exposure in Iowa.”

Most presidents act as consoler-in-chief in times of national crisis. Trump has struggled to show any empathy with victims or survivors of COVID-19.

Another hurdle for Trump in Iowa is the surge in Democratic voter registration before the party’s fiercely contested presidential caucuses in February, which has wiped out the GOP’s edge in the closely divided state. Registered Democrats now slightly outnumber Republicans.

Those new Democrats are one of the reasons that Jeff Link, an Iowa Democratic strategist, is not surprised that Trump’s campaign sees a need to shore up support in the state.

“They are smart to be spending here right now,” he said.

Finnegan reported from Los Angeles, Mehta from Toledo, Iowa.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.