Coronavirus could worsen death toll of summer heat waves, health officials warn

WASHINGTON — As summer descends on the U.S., public health experts are warning that the coronavirus could make intense heat waves deadlier, adding to the devastating death toll the country has suffered.

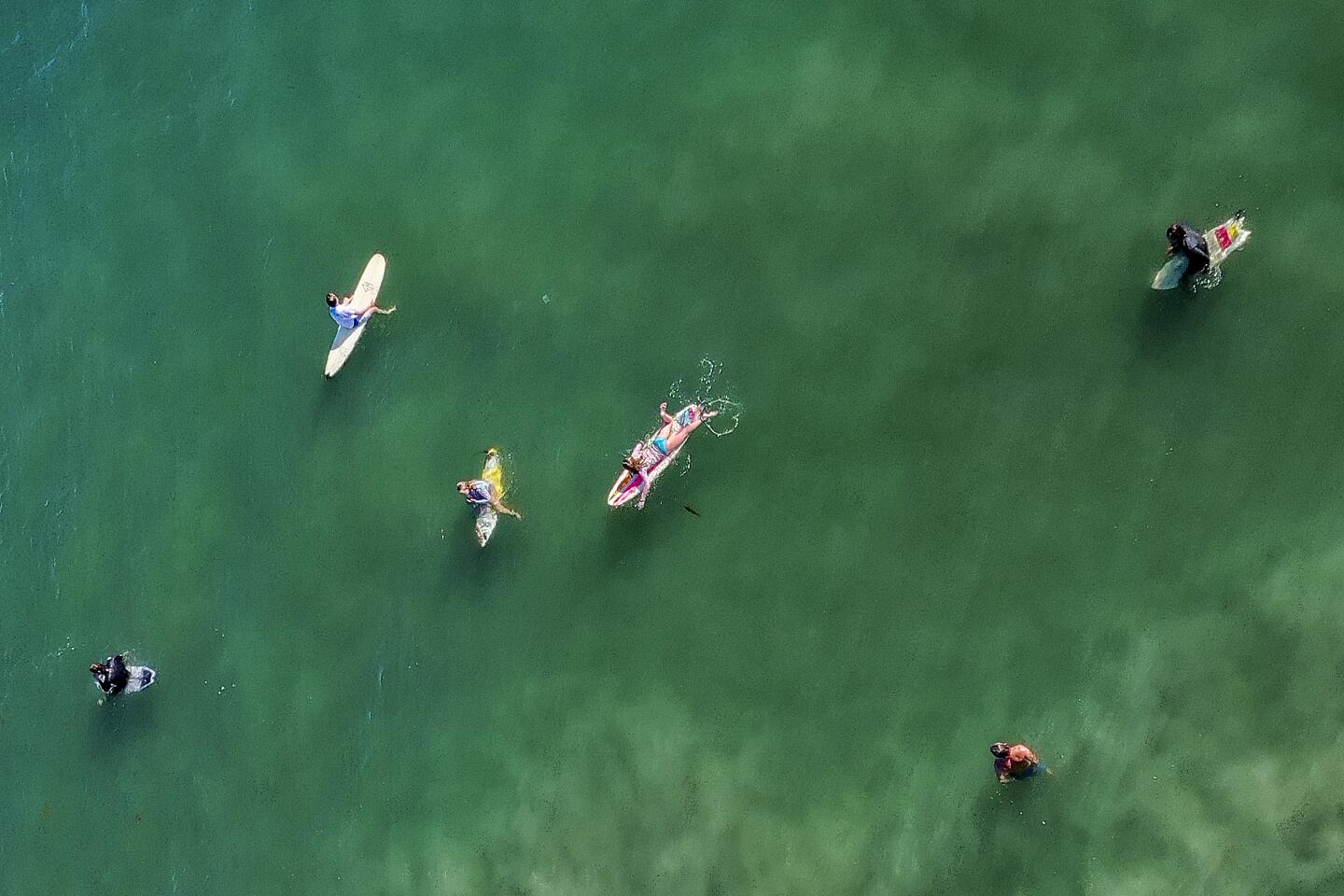

High temperatures have rolled through the Southwest unusually early this year, scorching Phoenix and Las Vegas and sending droves of quarantine-weary Southern Californians to the beaches.

Even before the outbreak, the hottest parts of the country were struggling to protect their residents from summer weather that, fueled by global warming, has become increasingly dangerous. Now the COVID-19 epidemic has presented them with an added crisis — the possibility of millions of people self-isolating in homes and apartments they can’t keep cool.

This is an especially worrying possibility for the elderly and people in poor neighborhoods, where residents are more likely to live in older, less energy-efficient homes and less likely to have air conditioners.

According to a 2019 study by USC scientists, about a third of households in Greater Los Angeles, and roughly half in neighborhoods near the coast, don’t have air conditioning.

Those who do have air conditioning but are living paycheck to paycheck may be reluctant to use it consistently to avoid high electricity bills.

Rupa Basu, chief of the air and climate epidemiological section for the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, said the virus’ effect could be amplified, in part, because it is killing people at higher rates who are already the most susceptible to extreme heat. For older people and Americans with chronic medical conditions, “it’s like getting hit twice,” she said.

In essence, the people who need to stay home the most are in the greatest danger of dying there during a heat wave.

“The messaging here is really tricky,” said Eric Klinenberg, a professor of sociology at New York University and the author of “Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago.” Health officials need to be honest about the dangers of the virus and who is most at risk, he said. But it’s also important for older people and those in poor health to know they shouldn’t sit at home alone all day.

“We have millions of people who are aging alone who feel like they need to stay indoors,” he said. “And social isolation combined with extreme heat is a proven killer.”

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Many Americans have been stuck at home, venturing out only to buy groceries or go for a walk, and those efforts at self-quarantining have been vital to slowing the spread of the virus in hot spots such as New York City and New Orleans. Yet that progress has not been uniform. Although some states are beginning to lift restrictions, urged on by President Trump, outbreaks continue to emerge in prisons, meatpacking plants and formerly untouched towns and counties in rural parts of the South and Midwest.

The administration has cautioned that without a cure or vaccine, some form of social distancing will probably remain in place throughout the summer.

With that in mind, cities have closed senior centers, libraries, public pools and gyms — places of refuge on blisteringly hot days — that could also become places of contagion during an epidemic. In California, state and local authorities have clashed over whether to close beaches.

Middle-class Americans can still retreat into their air-conditioned homes and cars, but for low-income residents and seniors on tight budgets, staying home during the summer could be dangerous.

Recent research by USC environmental engineering professor George Ban-Weiss and his team suggests that communities most vulnerable to extreme heat have some of the the lowest rates of air conditioning and the highest rates of poverty. In Compton, Inglewood and Lynwood, only about 40% of households have air conditioning.

None of the 6,500 units owned and managed by the city of Los Angeles’ Housing Authority come with air conditioning, not even in the San Fernando Valley, where summer temperatures can be especially punishing.

Eric Brown, a spokesman for the authority, known as HACLA, said that most of the city’s public housing was built in the 1930s and ‘40s, before air conditioning was considered essential. Residents are allowed to install their own window units if they get the agency’s permission, he said, which it has always given.

The situation is only marginally better in public housing managed by the county, where about half the units — including all of those occupied by elderly residents — have air conditioning.

In Arizona, where air conditioning can be a matter of life and death, public health officials and heat researchers are concerned about the state’s homeless population and people living in mobile homes built decades ago, before modern building codes.

Notoriously difficult and expensive to cool, mobile homes can easily surpass 90 degrees indoors during the summer. Their residents, who tend to be older, are already overrepresented among indoor heat-related deaths.

David Hondula, a climatologist who studies the impact of heat on health at Arizona State University, said that another factor researchers are paying attention to is substance abuse.

People who struggle with sobriety are at greater risk of dying from exposure to extreme heat, he said. A world upended by the coronavirus — in which 30 million Americans have filed for unemployment, anxiety is the norm, and addiction support groups including Alcoholics Anonymous have had to switch to online meetings — could make more people susceptible.

“The stress and worry of coronavirus could lead to increased use of those substances which impair one’s ability to cope with the heat,” Hondula said.

The combination of the virus and the approaching summer season is forcing health officials and emergency managers to rethink long-established protocols for responding to extreme heat. For the last month, public officials across Arizona have joined a weekly hourlong conference call to discuss strategies for providing shelter and distributing water without inadvertently spreading the coronavirus among the people they’re trying to serve.

When the first heat wave of the year arrived in the Southwest last week, enveloping the region in record heat for April, officials in Arizona and Nevada scrambled to open cooling centers for people who don’t have air conditioning at home.

In Maricopa County, Ariz., which spent five days under an excessive heat warning, the coronavirus complicated efforts. Many of the public buildings that would normally be converted into shelters had been closed down, their staff self-isolating at home, limiting the number of cooling centers that could be opened to the public and placing more of the burden on charitable organizations and religious groups.

Brande Mead, human services director for the Maricopa Assn. of Governments, a Phoenix-based regional planning group, said that donations of bottled water were also down.

“Water and other supplies can be hard to obtain right now,” Mead said. “In many of the grocery stores, the water aisle is empty.”

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has called on cities and states operating cooling centers to maintain at least six feet between people and to screen visitors, including conducting temperature checks, before they enter. “If possible,” the agency’s guidelines state, “provide alternative cooling sites for those showing symptoms of COVID-19.”

The agency also said that states should consider expanding programs that help people pay their utility bills, such as the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, as a way to lower the number of people using cooling centers.

In the aftermath of the coronavirus outbreak, about half the states issued orders barring utilities from turning off customers’ power, heat or water if they had overdue bills. In other states, customers are dependent on the generosity of their utilities companies, many of which voluntarily agreed to suspend disconnections.

But whether those suspensions will last through the summer is unclear. And there is considerable disagreement among social service providers and public officials about whether such steps actually benefit customers who’ve fallen behind on their payments.

In 2019, following news that an Arizona woman had died after her power was shut off for non-payment, the Arizona Corporation Commission — which oversees public utilities — placed a moratorium on summertime power disconnections. When the suspension ended in mid-October, some customers were left with staggeringly high electric bills.

It’s too early to say whether the suspension saved lives. Official heat-related death statistics for 2019 have not been released yet, but Hondula said the preliminary data show there was not a dramatic reduction. In Maricopa County, 196 peopled are thought to have died from heat exposure last summer, up from 182 the year before.

“Having one’s power cut is not the only part of the story,” Hondula said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.