Reopening the economy requires testing, and the U.S. still isn’t close

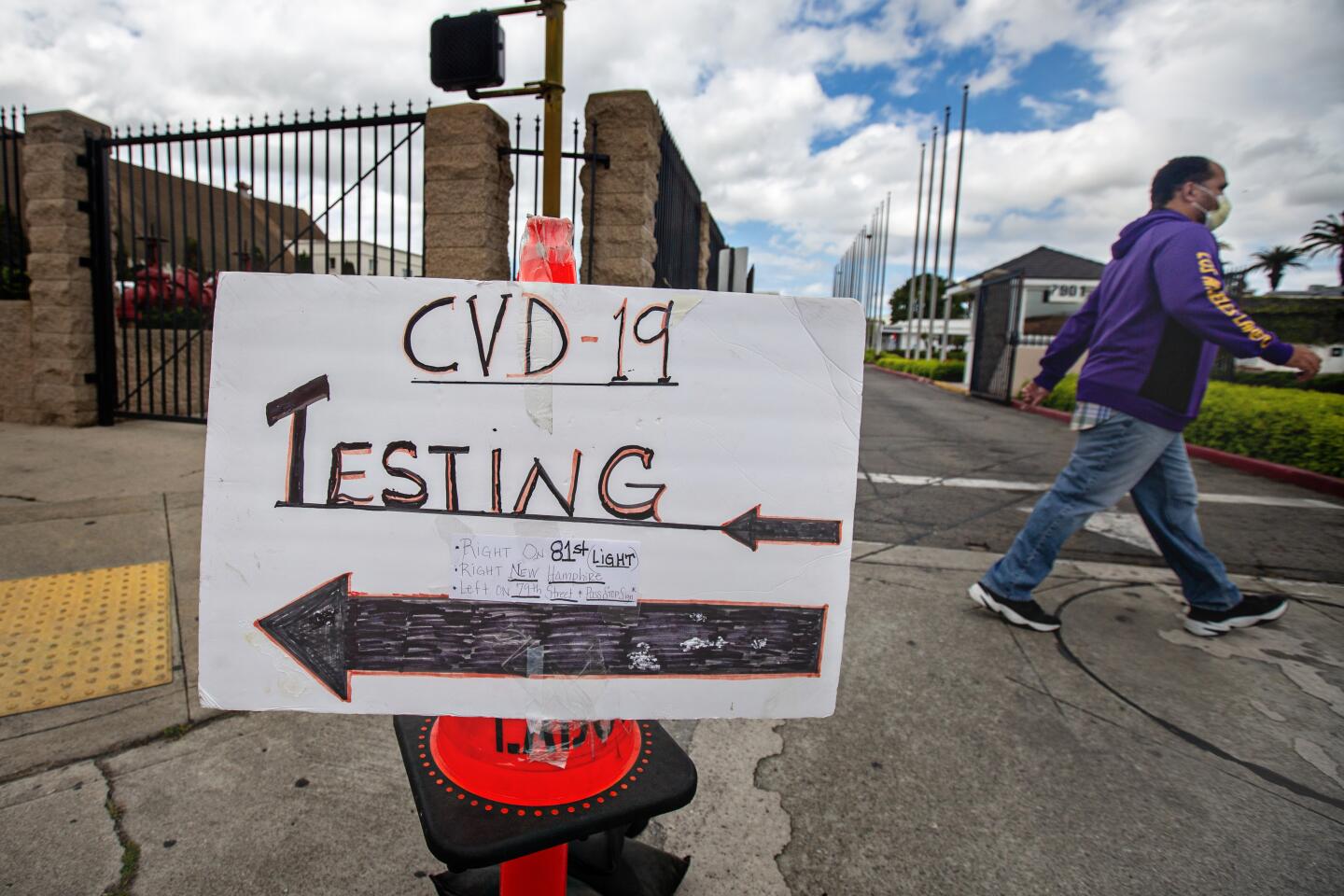

WASHINGTON — Six weeks after the president and other senior officials promised that any American would soon be able to get a test for coronavirus, testing continues to lag, prompting an escalating call from leading medical centers, lawmakers and others for the administration to put in place a coordinated national strategy.

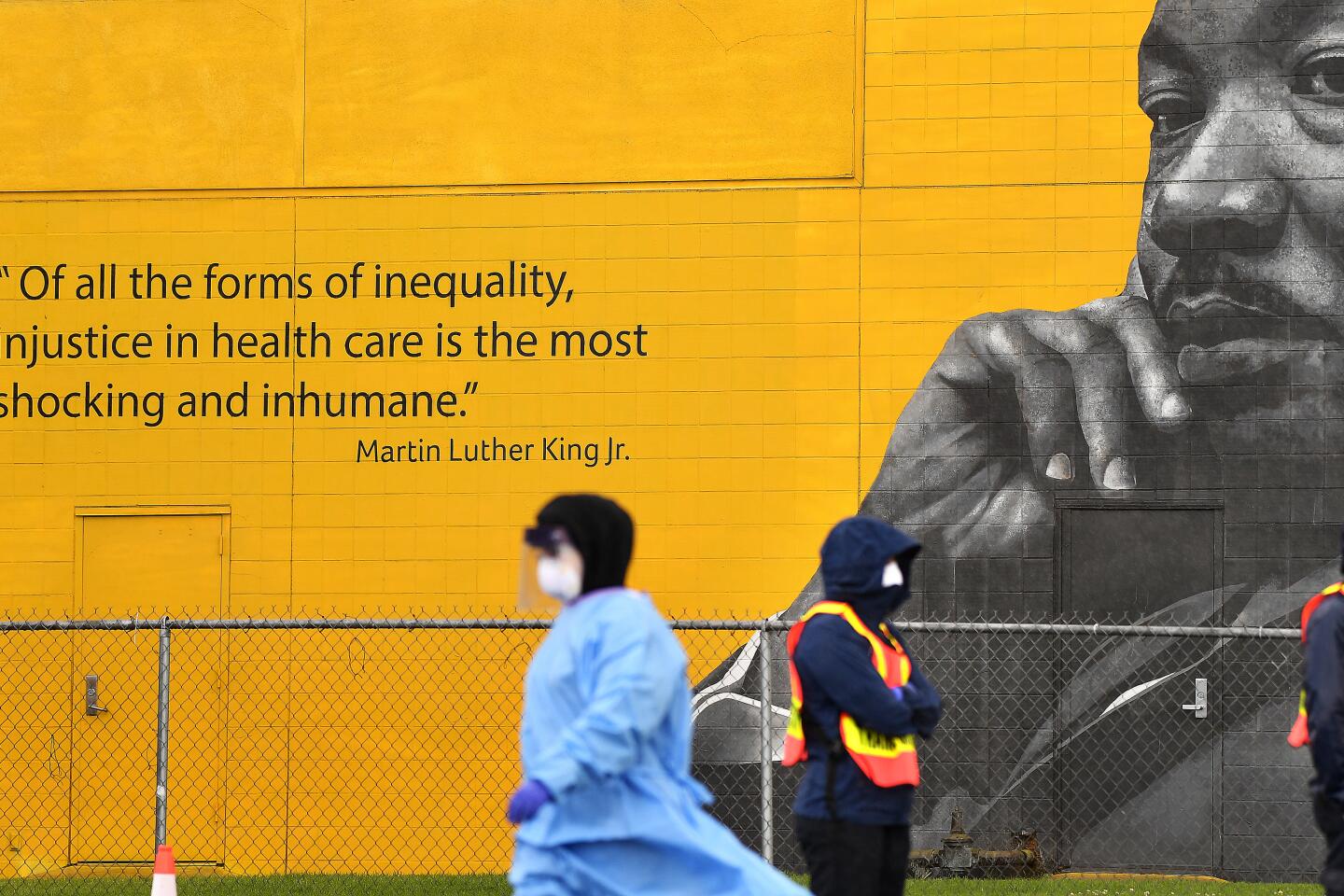

Effective testing is considered essential before state and local governments can lift restrictions on Americans’ movements, reopening schools and businesses and allowing the nation’s faltering economy to recover. But multiple, persistent problems continue to sharply limit the number of tests that can be done.

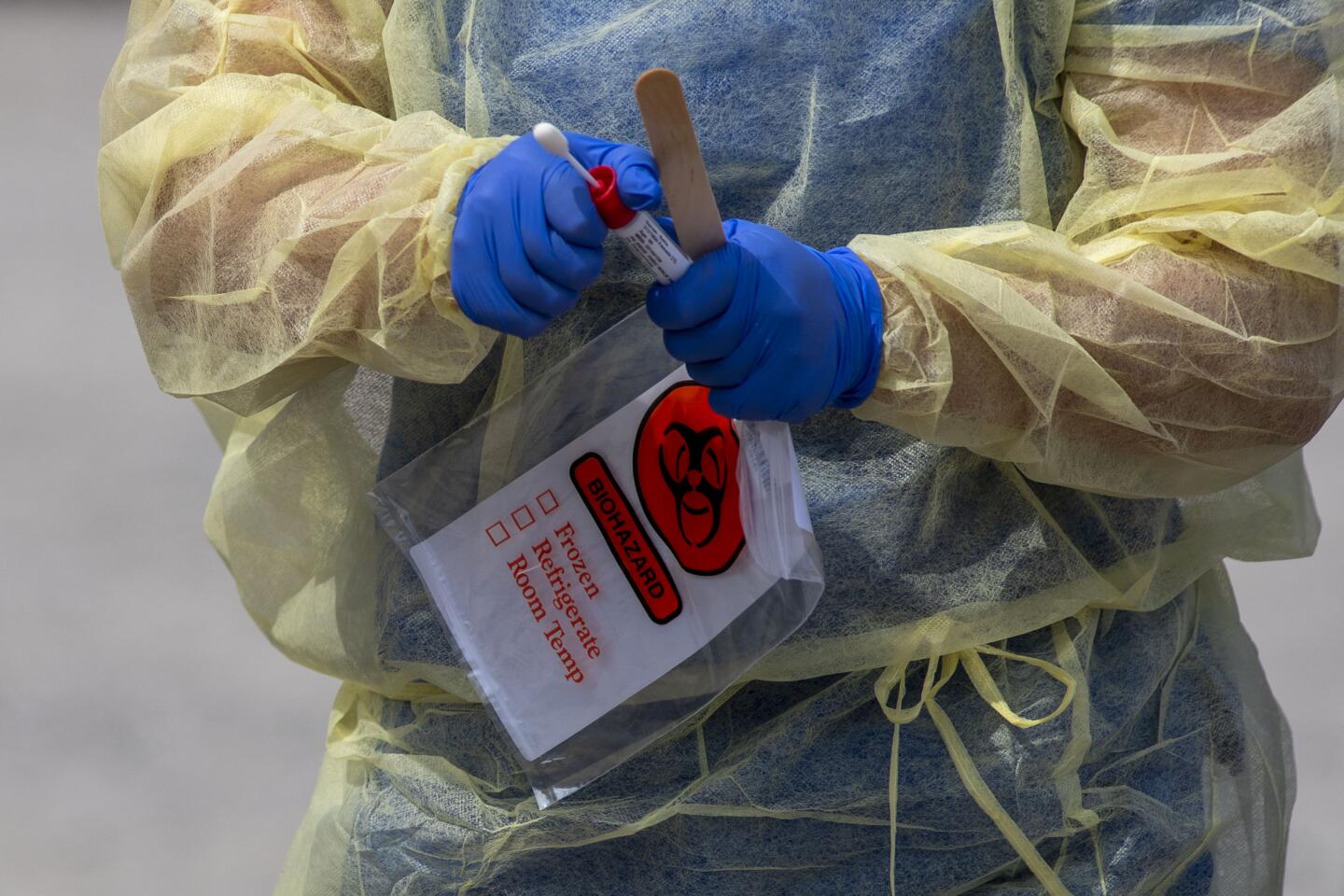

Labs remain short of supplies, ranging from simple cotton swabs used to take samples from patients to complex chemicals, known as reagents, needed to carry out the tests. Some laboratories report shortages of trained workers. Little coordination exists to shift samples from busier labs, which have backlogs, to others that have surplus capacity.

The White House and other administration officials haven’t detailed how they’re addressing the shortages, echoing the lack of transparency in the Trump administration’s work on other supply shortfalls, including insufficient numbers of masks, gowns and ventilators.

“The federal government can help remedy these challenges by taking a more definitive role,” Dr. David J. Skorton, president of the Assn. of American Medical Colleges, wrote to the White House on Monday. He noted that many academic medical centers lack adequate supplies to maximize testing.

“Our lab directors and institutions have their backs against the wall,” Skorton added in an interview. “They need help.” The association’s members include nearly 400 major teaching hospitals and health systems.

Across the country, public health experts say ending disarray in the nation’s testing is perhaps the single most important step to returning the country to normal activity.

“Right now, we are preventing the spread of the disease by extreme social distancing, by keeping people away from each other,” said Dr. Ashish Jha, director of the Global Health Institute at Harvard University.

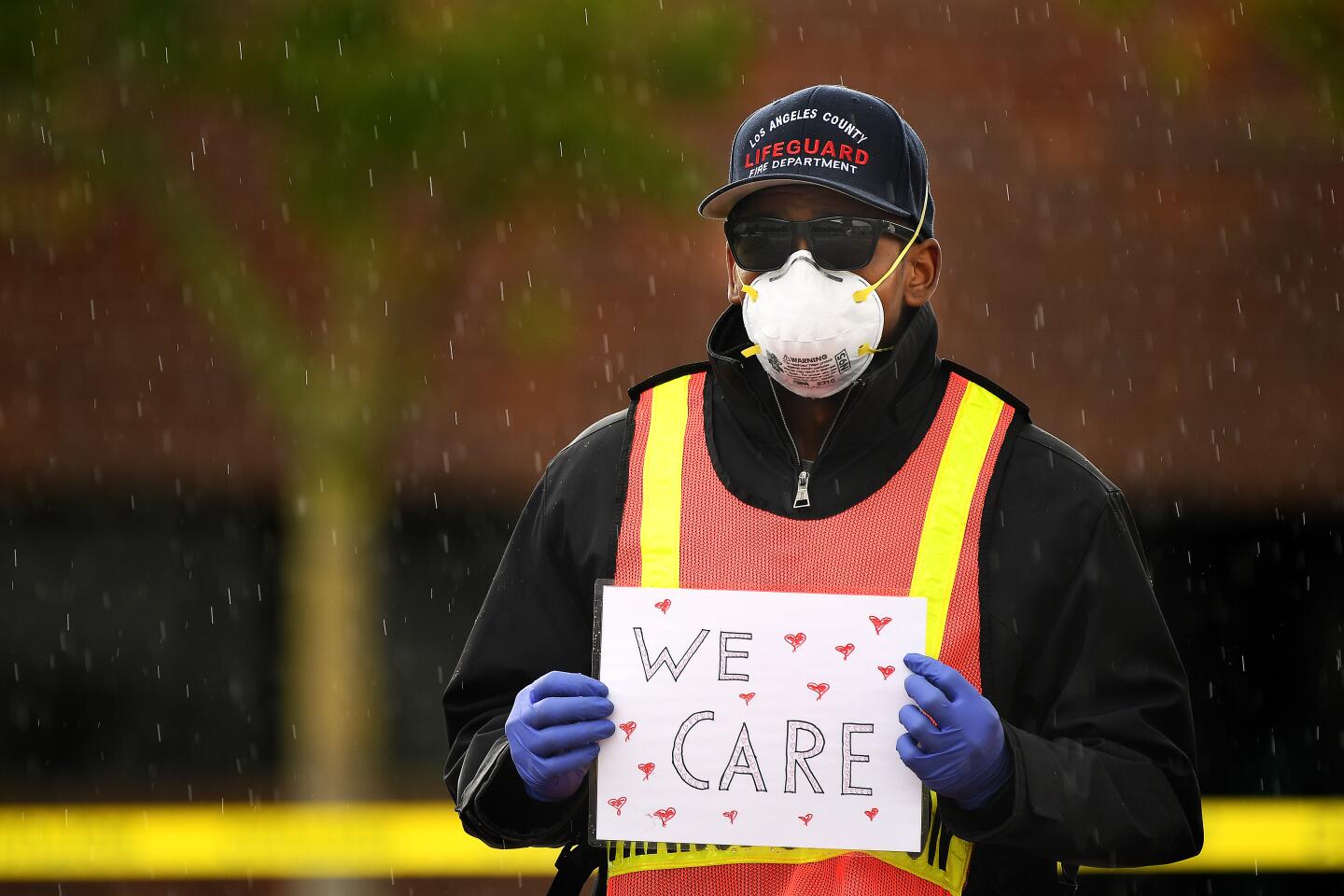

Firefighters and law enforcement officers from L.A. to Laguna Beach express their gratitude to healthcare workers for their efforts in fighting COVID-19.

“If we want to end that and let people interact with each other, we need to make sure infected people are not interacting with uninfected people. And the only way to know who is sick and pull them away from the uninfected is testing,” he said. “That is literally Disease Outbreak 101.”

Jha estimated that the U.S. would have to be able to run at least 500,000 tests per day before the current social distancing rules could be relaxed. That would be more than three times the current level, according to data from the COVID Tracking Project, which has been gathering state-by-state testing data.

On Capitol Hill, members of Congress are also stepping up demands for the Trump administration to act more forcefully to resolve the testing problem.

“Testing has been one of the weak links by the administration since Day One,” said Rep. Diana DeGette (D-Colo.), chair of the Energy and Commerce oversight subcommittee. The initial coronavirus tests developed by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in February were defective, leading to weeks of delay in rolling out testing.

Senate Democrats plan to outline their own national testing strategy Wednesday. They are expected to propose additional money to fix supply shortages and to build up public health departments. That would allow more extensive tracking of infected people and those they’ve been in contact with, another key step in reopening the country.

President Trump, who in recent days has been urging a swift return to normal activity, suggested last week that more widespread testing wouldn’t be necessary and this week indicated he might try to force state and local officials to lift restrictions soon.

On Tuesday, however, the president appeared to back away from a confrontation with states while minimizing federal responsibility for testing failures. “The governors are supposed to do testing,” Trump told reporters at the White House. “It hasn’t been up to the federal government.”

Dr. Anthony Fauci, who as the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has emerged as the federal government’s most trusted pandemic expert, cautioned Tuesday that testing would need to be more comprehensive before the current restrictions can be lifted.

“We have to have something in place that is efficient and that we can rely on, and we’re not there yet,” Fauci said in an interview with the Associated Press.

Coronavirus might have been in California as early as December. The timing had dire consequences

Testing capacity has been increasing at the nation’s largest lab companies, although the overall number of tests nationwide appears to have plateaued in the last couple of weeks, according to the COVID Tracking Project’s data.

LabCorp is now conducting about 40,000 tests a day at four labs across the country and has reduced the turnaround time on tests to between two and four days, company spokesman Mike Geller said.

And Quest Diagnostics now can perform approximately 45,000 tests a day at 12 labs across the country, including two in California, spokeswoman Kim Gorode said. She noted Quest has also eliminated the backlog of tests that had been delaying results and is now able to turn around results in one day.

Neither company reported problems securing supplies for the testing.

Despite their size, however, the two lab giants — which were feted by the president in early March at a Rose Garden news conference celebrating companies helping with the coronavirus response — still don’t have the capacity to do the amount of testing that many experts say will be needed.

Overall testing is also well shy of the promises made more than a month ago by Trump and other administration officials, including Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, who told a Fox interviewer on March 4 that more than 1 million tests were being sent to “hospitals and labs and others who want that.”

As of Tuesday, the country had run a total of about 2.9 million tests since the outbreak began three months ago, according to the COVID Tracking Project.

California, which has struggled to ramp up its own testing efforts, had performed more than 215,400 tests as of Monday, the state public health department reported. On Tuesday, Gov. Gavin Newsom said additional testing would be critical to reopening the state.

Gov. Gavin Newsom lays out the next steps in the weeks and months ahead in California’s fight against the coronavirus.

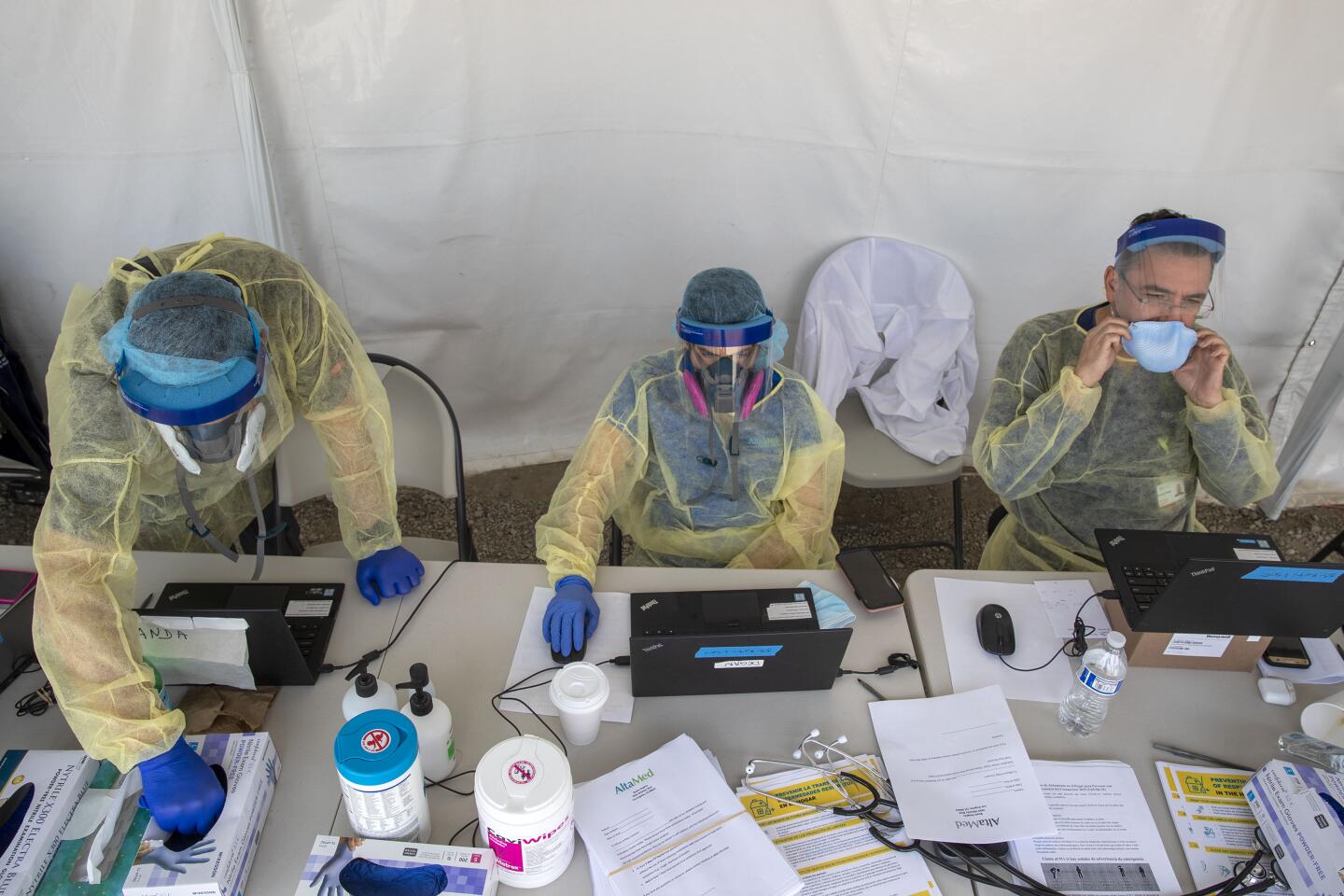

With commercial labs still working to add capacity, government public health labs and labs operated by major medical centers have been laboring to fill the gap.

But many continue to struggle to get supplies, with some missing swabs, others missing the reagent chemicals necessary to perform the tests and still others lacking other testing material, according to hospital officials around the country.

Compounding the problems, labs often must stock different kinds of supplies as different varieties of tests require different material.

“Few labs are able to maximize the testing capacity of any one machine, platform or test,” the Assn. of American Medical Colleges noted in its letter to Dr. Deborah Birx, who is helping to coordinate the White House coronavirus response.

Shortages of masks and other protective equipment, which continue to be a major problem for doctors, nurses and other medical staff, have also limited the ability of some medical centers to do more testing, health officials said.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency, which has been coordinating federal efforts to secure and distribute medical supplies, has sent testing material to states, a spokeswoman for the agency said, explaining that these supplies have been doled out based on states’ populations, with added shipments sent to coronavirus hot spots.

But this process has been shrouded in secrecy, as the Trump administration has refused to release details about how much material is being sent where and how determinations are being made about where need is greatest.

The medical colleges suggested the administration better manage the supply chain to get material to labs that need it and deploy a new web portal that would allow labs to quickly report shortages. The association also has called for more transparency in how supplies are being directed.

“This will allow lab directors and other institutional representatives to focus their time and resources on obtaining the platforms and supplies that are most readily available,” the association noted.

Times staff writer Jennifer Haberkorn in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.