As Trump lets private sector supply the coronavirus fight, the well-connected often get first dibs

WASHINGTON — As hospitals, doctors and state and local governments race for masks, ventilators and other medical supplies with little coordination by the Trump administration, the well-connected are often getting to the front of the line.

An outpouring of corporate and philanthropic support has funneled badly needed supplies to combat the coronavirus to well-known institutions such as Cedars-Sinai and UCLA medical centers in Los Angeles and the UC San Francisco Medical Center.

But in the absence of an overall nationwide distribution plan, many smaller hospitals, nursing homes and physicians are being left behind, especially those who lack relationships with suppliers, ties to wealthy donors or the money to buy scarce equipment at a time when prices on the open market are skyrocketing.

“It’s frequently all about who knows someone who knows someone who can get hold of this or that supply,” said Dr. Alex Billioux, public health director in Louisiana, which is battling one of the nation’s most aggressive coronavirus outbreaks.

“That unfortunately means supplies aren’t always equitably distributed,” Billioux added. The state often finds itself competing not only with other states but with its own medical centers, he said.

The competition for scarce supplies threatens to deepen inequalities in the nation’s healthcare system, putting Americans who live in more isolated regions of the country at highest risk.

The federal government has authority to manage the acquisition and distribution of medical supplies in a national emergency. President Trump hasn’t used that power.

Rather than direct federal agencies to establish a nationwide system, the White House has largely deferred to medical distribution companies, commercial suppliers and the generosity of manufacturers and charities to fill the gaps.

Many companies have stepped forward, including tech giants, automakers and others. But private companies don’t have to report where they send supplies or how they determine who gets assistance.

A spokesperson for Apple, for example, refused to provide any details about the company’s plans to distribute 10 million masks that Chief Executive Tim Cook said Apple secured.

Other donors expressed discomfort about being forced to decide who deserves aid.

“Where is the federal government?” asked Isaac Larian, founder and chief executive of Los Angeles toy maker MGA Entertainment, which last week announced it was working with its suppliers in Asia to procure 2 million masks for U.S. hospitals and other medical providers.

The head of one major West Coast medical system which has labored to secure its own supplies lambasted the Trump administration’s lack of leadership.

“There has been no coherent federal strategy,” said the executive, who asked not to be to identified out of fear of retribution from the White House.

For his part, Trump continues to insist that individual efforts will be sufficient and to suggest that hospital employees may be driving shortages by taking supplies “out the back door.”

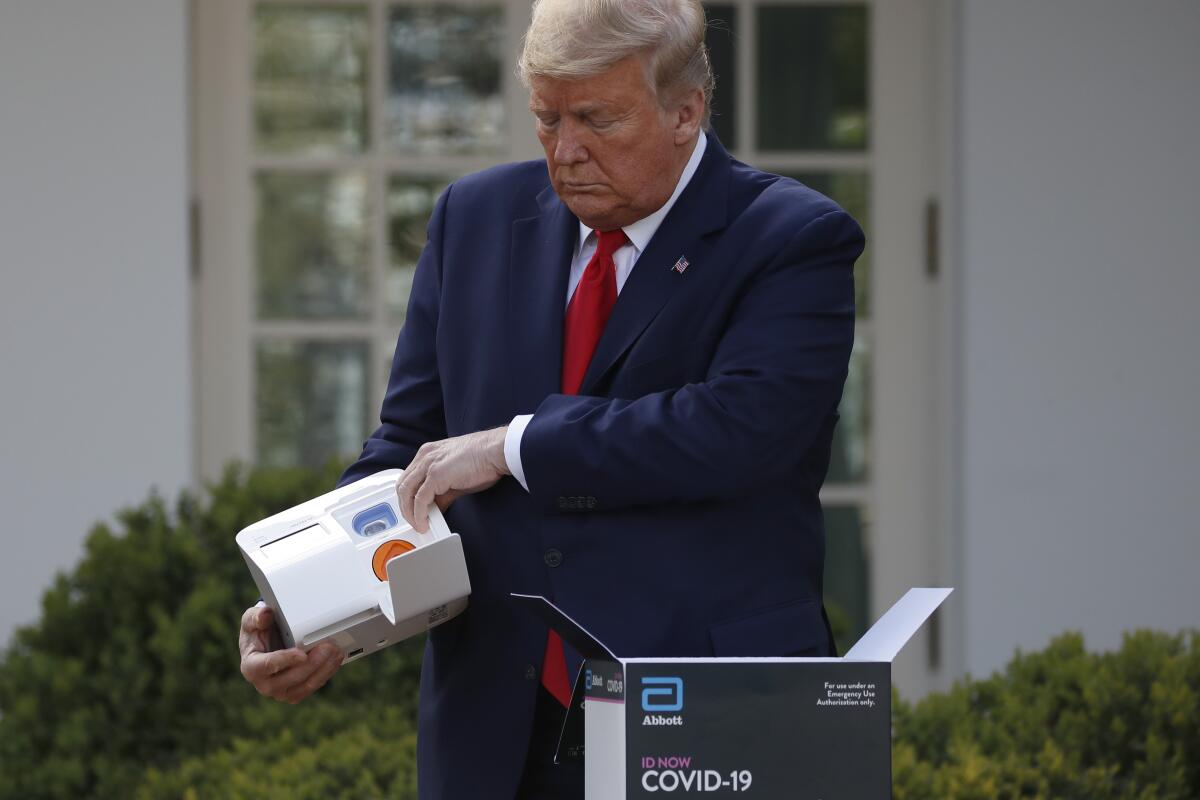

On Monday, the president hosted executives from five companies at the White House, inviting them to highlight their efforts to manufacture masks and other medical equipment.

But neither he nor the Federal Emergency Management Agency have outlined any plan for systematically distributing supplies, even though FEMA has begun to seize ventilator orders, according to hospital officials around the country.

Many healthcare leaders say they can’t get through to FEMA.

“The real frustration is not getting answers,” said a senior state hospital official, who also spoke on condition of anonymity, fearing reprisals.

FEMA hasn’t responded to repeated inquiries from The Times.

In Los Angeles, Larian, an immigrant from Iran, said he was moved to act after hearing from physician friends at UCLA and Cedars-Sinai about the desperate shortage of medical supplies. He said he tried to get in touch with FEMA to find out where he should ship the supplies. He couldn’t get his calls returned.

Larian directed the first shipment of supplies to UCLA, Cedars-Sinai and City of Hope, three of Southern California’s preeminent medical centers.

In the Bay Area, the UC San Francisco Medical Center, another one of the country’s leading hospitals, received a donation of masks from software giant Salesforce, which is also based in the city.

Other donors are similarly routing supplies to people and institutions they know.

Thomas Tighe, chief executive of Santa Barbara-based nonprofit Direct Relief, said he recently drove a shipment of masks to Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica after hearing from an emergency room physician he knew that medical staff there were reusing masks for up to a week.

Direct Relief, which typically distributes medications and supplies to poor countries around the world, has tried to develop a system for equitably distributing medical equipment in the U.S., focusing on community health centers that serve low-income patients. The charity is now working closely with the state of California.

But Tighe said his decision to drive the masks to Santa Monica reflected a lesson the group learned delivering aid in developing countries without well-developed systems.

“When you have a clean shot to help, you take it,” he explained.

There haven’t been major corporate donors or international aid groups to help in many other parts of the country, however.

In Gatesville, Texas, a community of about 15,000 some 125 miles southwest of Dallas, David Byrom, chief executive of the local hospital and nursing home, said he is fast running out of masks and gowns, even as COVID-19 cases are being diagnosed in surrounding counties.

The hospital, one of 157 that belong to the Texas Organization of Rural & Community Hospitals, was working through the trade group to get gowns to protect its workers.

This week, the organization tried to place an order for 50,000 gowns after finding a vendor who would sell them for $3.71 apiece. Then, the price jumped to more than $6, too high for the hospital group to pay.

“It seems like there is a lot of unethical behavior out there in the market right now,” Byrom said.

In California, Larian has been able to weather the steep run-up in prices, continuing to get supplies even as the cost of a mask shot up from $1.60 to $2.25, which is still less than some hospitals are being charged.

But Larian said he’s still trying to sort through the flood of pleas he is getting from hospitals and other medical providers across the country.

He routed more masks and other equipment out of California after a physician at UCLA told him that the medical center had enough for now.

“It was incredibly generous,” Larian said. “But it’s mind-boggling. Here in the United States of America, in the richest nation on Earth, it’s come to this.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.