Pete Buttigieg drops out of the Democratic presidential campaign

Pete Buttigieg dropped out of the Democratic presidential race Sunday, ending an improbable and historic campaign that cemented the gay former South Bend, Ind., mayor as one of the party’s young stars, but which struggled with the candidate’s short political resume and his lack of popularity with voters of color.

He narrowly won the Iowa caucuses and finished a close second in the New Hampshire primary. But poor showings in the next two contests, in Nevada on Feb. 22 and Saturday in South Carolina, suggested there was no plausible route to the nomination.

Buttigieg announced the decision Sunday night in a speech to supporters and staff in South Bend.

His departure just two days before Super Tuesday will likely boost other moderate candidates’ hopes of finally assembling a coalition large enough to compete with the progressive base backing Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont.

“The truth is the path has narrowed to the close for our candidacy,” Buttigieg said in his suspension speech, adding that to defeat President Trump, “We must recognize that at this point in the race the best way to keep faith with [our] goals and ideals is to step aside and help bring our party together.”

It had been an uphill climb from the beginning for Buttigieg, 38, who launched his candidacy from relative obscurity from South Bend, a Rust Belt city of about 100,000 people that had been on an economic upswing since the start of his eight-year tenure in 2012.

Not since the nomination of diplomat and Solicitor General John W. Davis in 1924 has the Democratic Party selected a candidate who had not previously won a statewide election as either governor or U.S. senator. Buttigieg had previously run for Indiana state treasurer in 2010 and for chair of the Democratic National Committee in 2017 and lost both races handily.

But the Republican Party’s nomination and election in 2016 of Donald Trump, who had no experience as a public servant, had broadened voters and experts’ perspectives on what was possible in a presidential nominee. The Democratic Party, still reeling from the loss, was undergoing an identity crisis and had no clear leader, which ultimately led more than 20 candidates to plunge in.

Buttigieg surged past multiple governors and senators through successful early media appearances on CNN and the liberal podcast “Pod Save America,” where the former Rhodes scholar and Navy intelligence officer impressed many listeners with the nimble and clear speaking style that would become the hallmark of his public appearances.

Buttigieg’s youth presented a stark contrast to the septuagenarians leading the Democratic field. He pitched himself to voters as a liberal who was nonetheless moderate enough to bring in independents and disaffected Republicans disgusted by Trump’s brash presidency.

The fact that he was a gay man from conservative Indiana lent historical weight to his presidential candidacy, which was a first for the Democratic Party; his husband, Chasten, a public school teacher, would become a cultural figure in his own right.

“I told Pete to run because I knew there were other kids sitting out there in this country who needed to believe in themselves, too,” Chasten Buttigieg said at his husband’s suspension speech Sunday night.

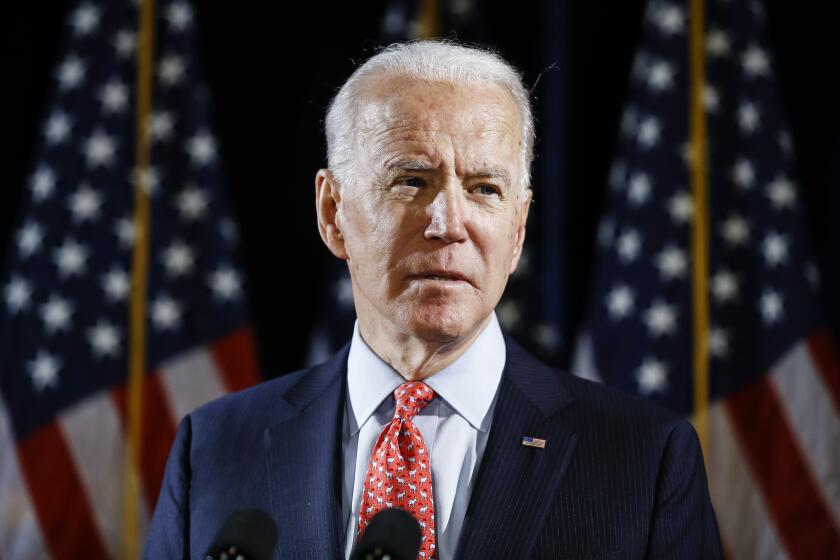

Buttigieg’s advisors sensed his unique biography and self-discipline would be a strength on the campaign trail, and — in contrast to candidates such as former Vice President Joe Biden — they made the South Bend native as accessible to journalists as possible.

The strategy helped boost his media profile on the cheap, and campaign contributions followed as big-dollar Democratic donors were particularly taken by Buttigieg, whose endorsers included Hollywood celebrities such as Kevin Costner and Mandy Moore. He also drew the support of prominent LGBTQ entertainers such as George Takei and Ellen DeGeneres.

The donations enabled Buttigieg’s campaign to swell to hundreds of paid staff and compete against his higher-profile and well financed opponents, but also marred his image as the Midwestern mayor-next-door after images leaked of a posh campaign fundraiser in a Napa Valley wine cave.

The fact that Buttigieg was even accepting large donations and holding private fundraisers in the first place marked an ideological departure from his fellow millennials, who were increasingly turning toward the kind of economic populism espoused by Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and who became some of Buttigieg’s harshest critics.

Buttigieg struggled to attract support from organized labor — he never received an endorsement from a single union — and he also received unfriendly headlines for his past work for McKinsey & Co., a controversial consulting firm known for cost-cutting and for its willingness to work with unsavory clients.

Buttigieg struck increasingly moderate positions as the campaign wore on, criticizing big left-wing ideas such as universal free college and a single-payer “Medicare for all” healthcare system, which Buttigieg rebranded as a less aggressive “Medicare for all who want it” public option. His campaign defended him from attacks from progressives by arguing that he was running to the left of where Hillary Clinton’s platform was in 2016.

His political inexperience also drew concern, particularly from critics who wondered if a woman with a similarly short resume would have gotten similar attention and credibility. “Could we be running with less experience than we had? I don’t think so,” Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota told the New York Times. “I don’t think people would take us seriously.”

Reviews of Pete Buttigieg’s legacy as South Bend mayor are mixed among residents of color — some positive, some outright hostile.

Ultimately, perhaps the issue that did the most damage to his campaign was Buttigieg’s failure to draw support from voters of color, not just nationally, but in his hometown. Although many black leaders in South Bend expressed their support for Buttigieg’s presidential candidacy, he had also been distrusted and outright disliked by some residents for his handling of the city’s police department.

Shortly after arriving in office in 2012, Buttigieg fired the city’s black police chief, who was accused of improperly recording police colleagues who were allegedly making racist remarks. The number of black officers in the department dwindled dramatically during Buttigieg’s tenure.

Those tensions exploded into the open during Buttigieg’s campaign in June 2019, when a white officer shot a black man who the officer said threatened him with a knife. But the officer’s body camera had not been turned on, leaving the incident shrouded in uncertainty.

At a town hall meeting that was nationally televised because of Buttigieg’s presidential run, residents unloaded angrily on the mayor, who sat somberly on stage and who acknowledged that his efforts to address residents’ concerns about policing “clearly haven’t been enough.”

Buttigieg stayed in the race and won a very narrow victory in Iowa over Sanders and came in second in New Hampshire.

For months, Buttigieg’s campaign had proceeded with the theory that his problem with voters of color was not dislike or distrust, but a lack of name recognition or excitement. They hoped that strong performances with white voters in Iowa and New Hampshire would swing open the door to Latinos in Nevada and, hopefully, black voters in South Carolina.

But by Saturday, it had become clear that the campaign’s grand strategy had failed. Sanders ran away with the Latino vote in a decisive victory in Nevada, and Biden gave a similarly commanding performance in South Carolina, where it was estimated that Buttigieg had support from only 2% of black voters.

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.