ALONG CALIFORNIA 33 — For nearly 300 miles along dramatic curves and desolate straightaways, State Route 33 passes seamlessly through California’s interior, exposing the attitudes and interests that divide it.

A drive from the beaches of Ventura to the outskirts of Stockton, from Democratic strongholds into Trump country and back, reveals befuddlement over the state of politics in America. There’s a common desire to come together, but no agreement on how to get there.

As California joins 13 other states in holding presidential primaries on Super Tuesday, many here are detached from the Democratic campaign that’s been unfolding for well over a year now, seeing little relevance to their own concerns or, worse, an assault on the way they’ve chosen to live.

The candidates’ vows to end America’s dependence on fossil fuels, shut down private prisons and safeguard wildlife by regulating land use may play well in the state’s left-leaning coastal cities.

Inland, along the road where oil rigs bob among tumbleweeds, where razor wire coiled around state prisons glints in the sun and billboards call for the building of dams, those promises sound more like misguided threats to jobs and economic growth.

The route begins: Ventura County

The interchange with Highway 101 that marks Route 33’s starting point lies only a few blocks in from a beach where surfers glide on the waves.

Downtown Ventura spreads out below the highway, a compact city of low-slung apartment complexes, restaurants, bars and beach shops.

“We’re divided — what do we do?” Ken Andreasen says with a sigh as he sips his morning coffee at the Sandbox, a cafe near the onramp to California 33.

Along a corridor that’s home to beach dwellers, hippies, artists, ranchers, farm laborers, mom-and-pop business owners, retirees and weekend warriors roaring through on motorcycles, people aren’t always eager to broadcast their party affiliations.

Having to coexist with both nature and people who hold opposing views is a necessity of life along Route 33, even if it’s not always an easy task.

Andreasen, an 80-year-old retired aerospace engineer, sees a glimmer of hope for the nation in the afternoon socials he goes to at a senior center in Ventura.

There, 25 to 30 people — staunch progressives, left-leaning independents like him and conservatives — come together to eat, play bridge, make art and attend Zumba classes.

“There’s moments when the whole room there is friendship,” Andreasen says. “If we can come together, maybe we can do it everywhere.”

About 15 miles into the drive, not far from the Mission-style arcades, New Age retreats and palm-studded citrus groves of Ojai, the Deer Lodge serves as the last pit stop before the road begins an hourlong, mile-high climb through Los Padres National Forest.

‘When you go off the road like this, you meet the heartbeat of America.’

— Mike Dawson, who grew up on the coast in Carpinteria

A faded poster on the wall by the bar sums up the mood of people who live along Route 33. Peter Fonda stares out over a barren desert landscape while wearing a leather biker jacket with an American flag on the back. The image is from the 1969 film “Easy Rider,” which was shot during an earlier period of political and social upheaval.

The caption on the poster reads: “God’s here. Where’s America?”

From there, the highway swings around hairpin curves, passes through tunnels blasted into rocky outcroppings and winds though ravines that close in like walls.

Suddenly the landscape is all meadows of sage-colored brush, then blankets of pines rising up vertical ridges.

As Route 33 skirts the top of a ridge, it twists back on itself to reveal the peaks of the Channel Islands towering over a supertanker in the Pacific.

‘This is what our grandparents had’

At an elevation of 5,100 feet, the cellphone signal drops and there isn’t a soul in sight.

A turn-of-the-century cottage comes into view in a clearing by the road.

Mike Dawson and his father-in-law, Dudley Zoll, stand outside the house, which they recently bought as a wilderness retreat.

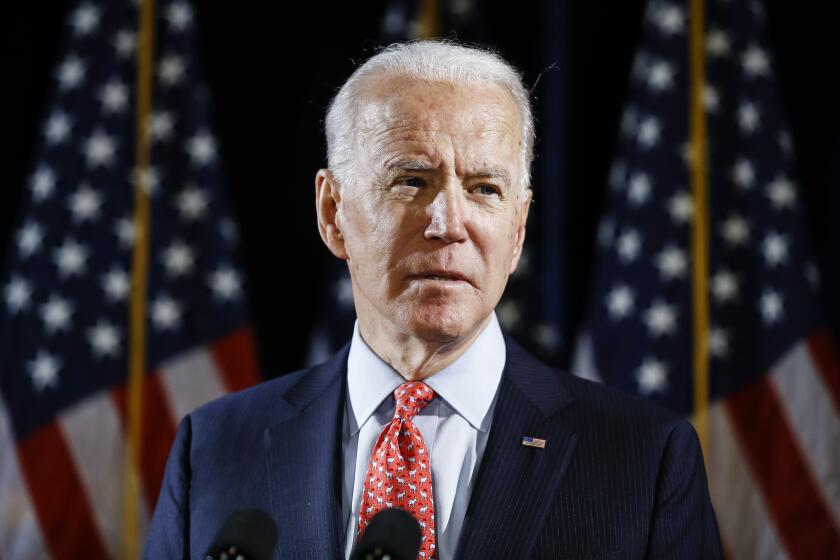

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

The men say they have no interest in discussing the election or politics in general.

Instead, as they linger in the shade of their matching straw hats, they relish the chance to talk about how it’s still possible to live the American dream along rural California’s isolated byways.

“When you go off the road like this, you meet the heartbeat of America,” says Dawson, 60, who grew up on the coast in Carpinteria and owns a construction crane business in Ojai, where he lives.

“These are the people that have worked hard down in the lowlands, and they come here and they buy a little homestead and they have a little weekly getaway. They come and howl at the moon at night — have a beer and enjoy themselves and listen to the wind,” Dawson says. “We have no power. We have no cellphones. We have no texting. This is it, man. This is what our grandparents had.”

In the flatlands, another California

About 50 miles north of its starting point, Route 33 catapults you back to those more optimistic days.

The road soars and dives through increasingly nerve-racking turns before coming to the edge of a sheer cliff.

Like curtains opening, the rocky hills that had hugged the road give way to a view of the golden-hued, southern fringe of the Central Valley — 2,000 feet down.

In this California, people measure the acres they own in the tens of thousands — and the populations in many of their towns in the tens and hundreds.

“The sign coming into town says 92, but I’d be surprised if there were more than 15 people living here,” says a server who didn’t want to give her name at the Place, the only spot to eat or drink in the tiny settlement of Ventucopa, which is miles from any full-size town.

There’s pecan and blackberry pie on the menu, but no talk of politics.

Route 33 streams past rusted-out tractors by the side of the road and between treeless hills covered with oil rigs before passing the one-stoplight oil town of Taft, the proudly conservative heart of Trump territory. Just one lonely “Trump/Pence” banner along the road declares the politics of this part of the state.

Locals have more existential concerns.

Some wonder how a state whose cities seem too crowded, whose cost of living seems too high and whose land seems too imperiled by fire, rain or the lack of — and too threatened by what appears to them to be overbearing federal and state regulators — can sustain the rural lifestyle that many see slipping away.

Around here, people have learned to ride with the boom-and-bust rhythm of the oil business. Times are especially hard in McKittrick, a blip of a town farther north that spans hardly one block, surrounded by oil rigs whose silhouettes resemble dinosaurs grazing on the plains in the late-day sun.

The presidential primary takes a back seat to the prospect that the town might go under.

Annie and Mike Moore first visited in 1961 as newlyweds. McKittrick was booming then and Annie had relatives in town, but Mike wasn’t impressed.

“Mike’s famous words were, ‘Who in the hell would live in a godforsaken place like this?’” Annie says with a laugh as she gives a tour of Mike & Annie’s Penny Bar, the watering hole they opened two decades ago after deciding to resettle here.

Pennies, over a million of them, cover the bar’s walls. Mike glued them in place one by one over the years.

Mike died in January. Among the few times in recent memory when the place was standing-room-only was for his wake, says Annie, 77.

The good times, captured in dozens of old photographs of smiling customers pinned to the front dining room walls, seem long gone.

“Friday and Saturday nights, this was the place to be,” says Jacqueline Ballou, one of the Penny Bar’s handful of employees.

Ballou, 55, has worked here on and off for 13 years.

“It’s hurting,” Ballou says of the bar.

Both women say that restrictive state drilling regulations have led energy companies to downsize, and that meant a steep drop in customers.

Annie’s pessimistic about the future. Financial problems and other issues have led her to consider shutting down for good.

“I just keep praying,” she says.

James Dean, cow patties and Coalinga

As the sun goes down on Route 33, passing cars are few and far between. Then a familiar face appears in the distance at a gas station in Blackwells Corner, a junction about 40 miles north of McKittrick.

It’s a towering cutout of Hollywood legend James Dean, inspired by his movie “Rebel Without a Cause.” Dean wears a red jacket and blue jeans, with his legs crossed, and he stares down on the highway with a look that says he’s trouble.

This is thought to be the last place anyone saw the 24-year-old actor alive on the afternoon of Sept. 30, 1955, as he made his way to a road race. The Porsche 550 Spyder that Dean was driving collided with another car at a junction west of here, killing him.

For the next hour, Route 33 changes again, passing scrubland, fruit orchards and prisons before landing in Coalinga, a town of 13,300 set in a dewy valley.

In the mountains, the air fills with the scent of pine and brush, and on the plains, dust. Around Coalinga, the funk of cow manure signals your arrival into one of the biggest cattle ranching regions on the West Coast.

Nearly 200 miles from where Route 33 started, this is also God’s country.

“Jesus is Lord of Coalinga,” a rainbow sign proclaims just outside town across the highway from a field where a herd of buffalo grazes.

The next morning, ranchers Teddy Den Hartog and Gary Jackson keep their cowboy hats on for their breakfast of hamburgers at Cafe 101, a family-owned diner decorated with signs and memorabilia celebrating another of the state’s fabled highways, Route 66.

They’re more worried about the influence of the powers that be three hours north in the Democratic-controlled Legislature in Sacramento than the one exalted in the rainbow sign.

The men look uneasy at first as they gently rib a reporter from L.A. for living in what they consider to be a liberal cesspool, but they soon open up.

“What makes us happy about living up here is being out of the Bay and L.A.,” says Den Hartog, who lives on more than 20,000 acres of ranchland that’s been in his family since the 1860s.

As a solidly conservative community, far from urban centers whose problems attract more attention, “we have no vote,” the rancher says.

Den Hartog, 66, says his roots may run deep here, but he feels out of place in today’s California, whose taxes and regulations he considers to be out of control and whose leaders he believes don’t value the voices and experiences of rural residents like him.

He’s thinking of moving to Idaho.

“I’m pulling the plug,” he says.

Pea soup and principles

The highway stretches on, past miles of nut and fruit orchards and past fields covered with solar-energy panels before reaching the tiny outpost of Santa Nella, home of Pea Soup Andersen’s, a Scandinavian-themed truck stop that has a giant windmill spinning by the parking lot.

Rudy Recile and his wife, Sally Castillo-Recile, sit in a booth eating pea soup. He’s wearing a polo shirt with an image of the Declaration of Independence printed on it, and she’s wearing a red, white and blue T-shirt that says, “Make some sparkle.”

“I was feeling patriotic today,” Sally says with a smile.

Rudy and Sally, both 51-year-old Army veterans, live in Vacaville in Northern California. They were driving south along Interstate 5, which merges with Route 33 in this part of the state, to attend a nephew’s graduation from Army boot camp in San Diego.

“This place is awesome, and one of the reasons I love it is because it’s been here forever,” Rudy says.

But he fears that other things — like family, community and the nation’s unifying principles — may not endure.

“Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” Rudy, who preferred to describe himself as a conservative rather than identify which party he tends to vote for, says he reflects on that phrase in the Declaration of Independence every day.

He thinks it’s time for all Americans to renew their sense of shared responsibility for the country’s well-being.

“Everybody’s saying that we’re divided, that this is a bad country — but we’re all Americans,” he says. “We live in the greatest, most prosperous country in the world. Enjoy what you have.”

Nearing the end

Route 33 straightens after Santa Nella as it heads north.

In the farming town of Patterson, locals were feeling pressures of their own.

California’s housing crunch has made the former “Apricot Capital of the World” both attractive to bargain-hunting outsiders from the Bay Area 80 miles west and increasingly costly for the longtime residents.

The town’s population has doubled to about 23,000 since 2000, and encampments of the homeless have sprung up by the railroad tracks that run along Route 33.

The Democratic presidential candidates have proposed bold plans to move the low-income families and the homeless into affordable housing.

Those plans can’t materialize soon enough for Julia Medina, one of about two dozen people who built dwellings in what locals refer to as “the cages,” an unauthorized homeless encampment on a lot filled with metal-mesh storage containers next to the railroad tracks.

Medina, 62, stood with tears in her eyes at her dwelling, a container the size of a walk-in closet that was designed to transport produce and now held her clothes, cookware and a small bed where her three dogs played. Old cars, blankets and pots and pans littered the muddy area outside her shelter.

Sheriff’s deputies tried to get residents to leave because they were trespassing. Medina, who has lived in Patterson most of her life, said she had nowhere else to go.

For her, the question of how to make a life in California isn’t political. It’s deeply personal.

The container she transformed into a living space may not be much, but in a state that’s failed to solve its homelessness crisis, and in a country with a widening gap between rich and poor, this is home.

“I don’t know how to live anywhere else,” Medina says.

Route 33 ends near Stockton at an unremarkable tangle of highways among orchards, cow pastures and clusters of suburban townhouses that look awkwardly out of place.

Even with all the challenges that communities face along the 290 miles of Route 33 — the boom-bust cycle, fires, floods and droughts, along with poverty, not everyone is ready to give up on California.

Or the country.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.