LAS VEGAS — The road between Las Vegas and Reno traverses some of the emptiest land in the continental United States. Wild burros idle across the asphalt, gutted miner shacks cast scant bits of shade, the faded signs of long-gone brothels creak in the wind.

People seeking fortune came and went. But in the two thriving ends of that desolate drive, they came and kept coming, seeking more modest dreams: an affordable home, low taxes, a union job, a break from the past.

They poured in from California, Arizona and Hawaii, from Mexico, the Philippines, El Salvador, China, Cuba, Iran, Eritrea. Even in this mostly empty chunk of planet, more than 90% of all Nevadans live tightly in the Vegas or Reno areas, making it the third-most urbanized state in the nation — and the first test of a truly diverse electorate in the Democratic presidential nominating contests.

Both cities are something like satellites to their coastal counterparts to the west, more connected to Southern California and the Bay Area than to each other. In that sense, the caucuses here on Saturday are a taste of a much bigger electoral bounty when California votes on March 3.

The latest live results and maps from the 2020 Nevada caucuses.

The Emigrant Trails no longer cross Nevada; they end here. Some of the most-traveled routes today come from the west by air, land and sea, crossing the Pacific.

Amie Belmonte, born in the Philippines and raised in Hawaii, moved to Las Vegas from Honolulu in 1996 when her husband, Leo, was offered a management job at the Federal Aviation Administration. Devout Christians, they had been leery about moving to Sin City, but found a church they liked with a Japanese Hawaiian pastor and fell in love with the low prices of homes.

They got friends and family to follow. “When we tell them you can come here and own a home for $300,000 or $500,000, they come,” Belmonte said. “I brought over 100 people here. I could have a reunion here just of people in my high school in Honolulu.”

The Filipino American population in Clark County doubled in a decade to 117,000 people in 2015 (more than twice the number of all people in the county in 1950).

The Latino population did the same between 1990 and 2000, rising to 300,000 — and now to more than 650,000, even with the housing market collapse temporarily devastating the economy here.

This tilted the state from a moderately conservative backwater to a moderately liberal slice of the Western electorate.

“We have diversity within diversity,” said Robert Lang, a professor of urban affairs at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “Clark County looks like America is expected to look in the mid-21st century.”

::

Las Vegas has long had the reputation in Reno that Los Angeles had in San Francisco: a boorish, soulless upstart that grew way too fast.

Greater Las Vegas has three-quarters of the state’s residents, 2.2 million people. The population of the Reno metro area is about 465,000.

The rest of Nevada is a smattering of small towns surrounded by an emptiness of “inhuman scale,” to use Wallace Stegner’s words.

Nevada’s mountains were the original great gamble, 150 individual ranges among them, hiding veins of gold, silver and copper. Since the historic Comstock Lode strike in 1859, miners set out in every direction, establishing a boom-bust cycle that itself is yet to bust.

Natives were displaced as longer-term settlers moved into the watered spots. Mormons farmed the river valleys, planting their Lombardy poplars for dashes of green, and ranchers ran their herds in the steppes. Snow-melt rivers flowing from the Eastern Sierra blessed the Truckee Meadows and Eagle Valley, and in that belt of land below Lake Tahoe, the first stable cities grew, Reno and Carson City.

Three hundred miles away — and four decades later, at the turn of the century — Las Vegas was still just a meadow and watering hole on the old trail from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles. When the Union Pacific laid down tracks, it decided to put a station and repair shops there, and in 1905 auctioned off 110 acres for a city. From that, the seed sprouted, slowly.

With only 8,500 people by 1930, Las Vegas might have remained a small railroad outpost, like Needles or Barstow.

But the next year, construction began on nearby Hoover Dam, bringing an influx of workers. And Nevada legalized gambling at the perfect time.

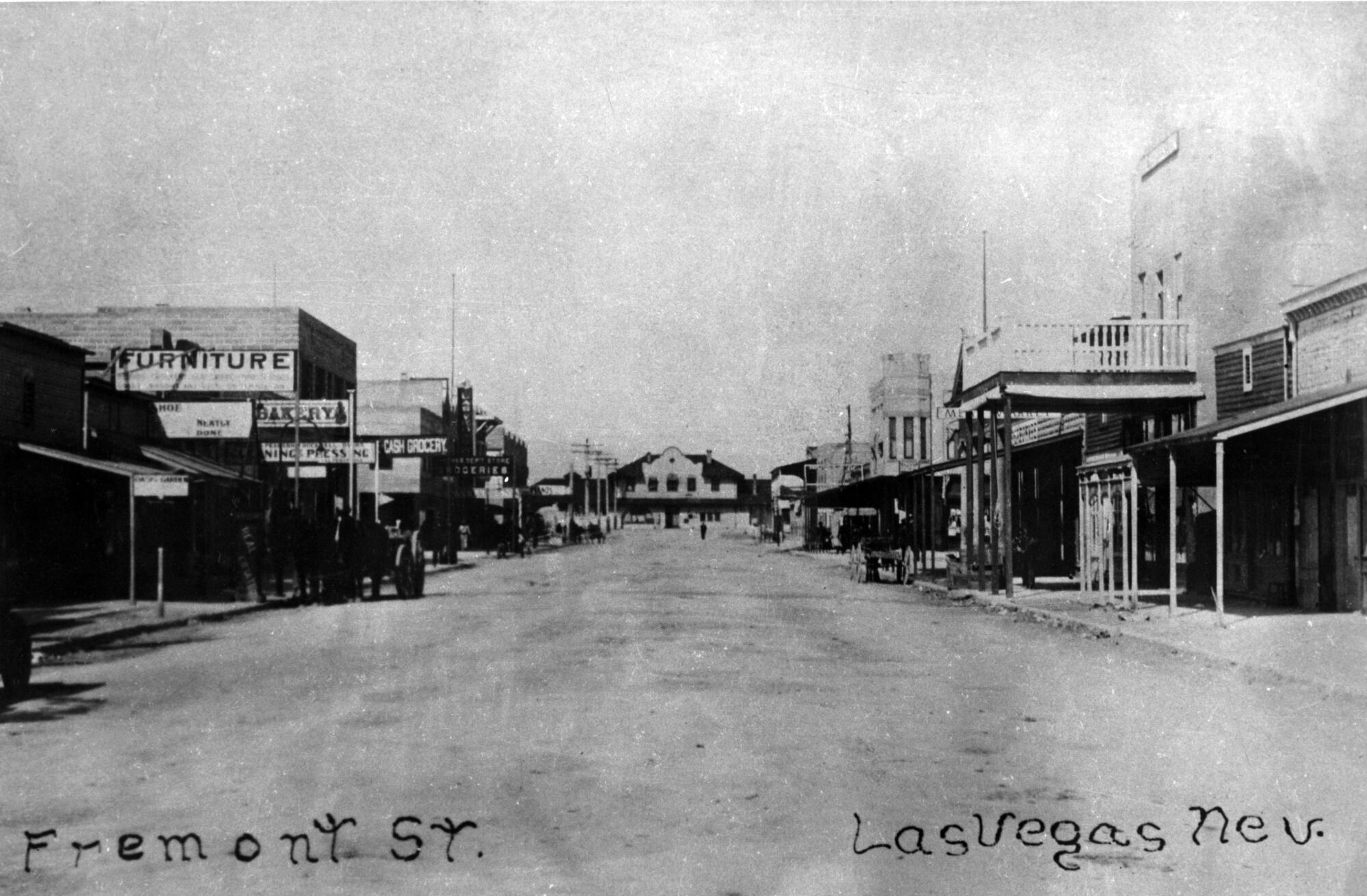

Southern California sheriffs were shutting down mob gaming ships and bingo parlors, and many of those operators — and their customers — simply headed a couple hundred miles up Highway 91 to the growing casino district on Fremont Street called “Glitter Gulch.”

The dam turbines powered the glitzy lights and something more critical for Vegas to survive: air conditioning.

From that point, the city was inextricably tied to Southern California.

When Steve Perkins, 50, grew up there it was a town of Mormons, mobsters and military from Nellis Air Force Base. He and his friends roamed the desert catching lizards and shooting BB guns, finding their way back by using the distant tower of the Mint hotel as a landmark.

It was a unique place in the extreme. Howard Hughes had holed up on the 9th floor of the Desert Inn and bought a local television station to play movies that he could watch at night. The whole city put up with his whims. When he didn’t like a film, he’d call the station to change it. “You’d be watching Channel 8 and the movie would just stop,” Perkins recalled.

His grandfather Philmore Rothstein had moved to Nevada after World War II. He was an accountant by trade and had run a numbers game back home in Scranton, Pa., where he had mob connections, Perkins said. He started running the keno games in Vegas, moving from casino to casino — the Tropicana, the Golden Nugget, The Hacienda — skimming the profits for bosses back in Kansas City, Detroit and Chicago.

When Perkins was born in 1969, the population of Clark County was about 273,000 and Las Vegas still had a small-town feel.

“Up until the late 1980s, you could see someone’s name and know what field they were in,” Perkins said. “The Foleys, they were judges and lawyers. The Christensens were firemen.”

Given the state’s motley mix of union workers, military families, miners, retirees, Mormons, ranchers, casino magnates, Nevada became a remarkable bellwether for the presidential elections, picking every winner but one, from Woodrow Wilson in 1912 to Barack Obama a century later.

“Nevada tends to be a trend line for the rest of country,” said Michael Green, author of “Nevada: A History of the Silver State” and a professor of history at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Las Vegas leaned Democratic when Perkins was growing up, though it was not exactly liberal. Segregation was an unwritten rule. Black people were pushed into an unpaved, rundown stretch of West Las Vegas. In the early days of the casinos, Sammie Davis Jr. and Louis Armstrong were not allowed to stay at the resorts where they performed. Mexican Americans were relegated to similar conditions on the east side.

“We were the Mississippi of the West,” Perkins said.

One of the few people of color in his junior high school was Marco Rubio, the future Florida senator, whose family came from Miami in the 1970s. Cuban exiles had a small foothold in town, trickling in after Castro shut down the mob-run casinos in Havana.

Other mini-pipelines opened: Samuel Boyd started the California Hotel and promoted it heavily to Hawaiians, who came to gamble in droves. They found a service economy similar to what they’d had at home, with a vastly more affordable cost of living, leading so many to settle here that they dubbed Vegas the “9th Island.”

One of Perkins’ neighbors was Arturo Catacutan Casimiro, a celebrated bartender at Don the Beachcomber in the Sahara hotel who was known for spinning whiskey bottles in the air with his eyes closed and opening beer bottles with one hand. Casimiro, now 79, was one of the first Filipinos in town.

His son Noel became friends with Perkins in high school. They drank, got high and rode in noisy caravans to parties at other high schools to meet girls. “I thought money was everything, what you drive was everything,” Casimiro said.

Neither went to college — Vegas didn’t promote education much back then, in their view. They became valets parking cars at casinos, making $30 an hour out of high school.

Perkins realized this could not be his life’s calling. “I wanted to be a firefighter, but the Mormons had that locked up.” He started doing information technology for the casinos.

Casimiro was a natural performer like his dad, and ran nightclubs and staged raves, living the party life before getting into the real estate and mortgage market, riding the boom like so many Nevadans before him.

With Ronald Reagan running for president, the Republican Party started to gain traction, particularly as retirees from California poured into Nevada for its low taxes. Many of the New Deal descendants turned into Reagan Democrats, who often voted Republican.

“The Democrats were really conservative back then,” said Eric Herzik, a professor of political science at University of Nevada, Reno. “People would from the Northeast would say, ‘You’re Democrat?’”

But big demographic changes were in the wind. In 1989, Steve Wynn opened up the first mega-resort, the Mirage, ushering in a new era on the Strip that largely turned the city into what it is today.

Old casinos were dynamited to make room for massive luxury hotels: the MGM Grand, Bellagio, the Venetian, Mandalay Bay, Paris Las Vegas, the Palazzo. Workers streamed in to build the resorts, as well as the sprawling subdivisions needed for the huge influx of people coming mostly from Southern California.

The city surged from 741,000 in 1990 to 1.95 million in 2010. The Latino community ballooned from 83,000 to 567,000, jumping from 11.2% to 29.1% of the population, while African Americans grew from 9.5% to 10.5% and Asian Americans increased from 3.5% to 9.4%. With Clark County leading the charge, Nevada turned solidly blue.

Now the Democratic presidential candidates are leaping from point to point over the devoid expanse between Clark and Washoe counties, trying to prove they can win over voters of many colors.

In Nevada, such fast growth left gaps in certain services. A shortage of healthcare workers pushed hospitals to recruit nurses from the Philippines to fill the void. In 2012, Belmonte helped create a group, FilAm POWER, pushing Filipino Americans to run for state and local seats in Nevada, with four candidates on the June primary ballot. “We need representation,” she said.

“Clark County looks like America is expected to look in the mid-21st century.”

— Robert Lang, a professor of urban affairs at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Drive a typical suburban thoroughfare, like South Rainbow Boulevard, and you’ll see the breadth of humanity that has come to live here reflected in the strip malls: POTs Egyptian cuisine, Roberto’s Taco Shop, Honey Baked Ham, Bobo Hut Hawaiian Chinese fusion, El Congo Salvadoran restaurant, Mr. D’s Sports Bar & Grill.

All this growth carried a risk. When the housing bubble burst in 2008, nowhere was hit harder than Vegas. Nearly 1 in 8 housing units were foreclosed in 2009. The seemingly perpetual growth came to a halt. Casimiro lost 90% of his income when his wife was eight months pregnant.

“I lost everything,” he said. “My house was foreclosed; my BMW was repossessed.”

But he reassessed his priorities and devoted himself to family and a newfound faith in God. Like the city, he slowly recovered.

“We rose out of the ashes,” he said.

What happened in Las Vegas did not stay in Las Vegas.

Reno, in Washoe County, had become its own much smaller gaming empire, and it saw a tide of people moving over the Sierra from the Bay Area. Logistics companies and tech firms like Tesla, Switch, Panasonic and Apple are setting up big operations in the dusty hills east of town, once known only for its brothels.

Latinos — a quarter of Washoe County residents — are just beginning to flex their muscle. Diana Garcia, 21, remembers how her family moved out of their neighborhood in Reno because a white neighbor kept harassing them.

Her mother, a housekeeper and an immigrant from Jalisco, moved through eight different hotels because her bosses didn’t pay her or otherwise mistreated her. At one point, the hotels were giving housekeepers too much work to complete on a single shift, and many of them clocked out, per the rules, but kept working for free.

Garcia enrolled at the University of Nevada, Reno, three years ago, and felt out of place for the first two years because it was so white.

“A majority of Latino students drop out because they don’t feel part of the community,” she said. But she discovered an advocacy group, Latino Research Center, in a quiet corner of campus, and is now pushing for more programs to recruit and help Latino students.

Herzik says that where Las Vegas is blue, Reno is “a wash.” The flow of younger, educated people over the mountains looking for tech jobs — not just tax breaks — has pushed the needle of the onetime Republican garrison to the left, and it’s bound to go further, especially as more and more young Latinos reach voting age.

But rural Nevada remains red, relying on military bases and testing sites, and mining and ranching on federal lands.

Tonopah sits halfway between Reno and Vegas. No presidential candidates have visited to this point, but there are rumors that Tom Steyer’s campaign bus broke down outside of town.

To get there from either city, drivers follow U.S. 95 for hundreds of miles, between craggy ranges, salt lakes and cinder cones. The road threads through valley after valley, their floors rising and falling like great groundswells that stretch for miles, with abandoned settlements littered about. When a business or town dies in the desert, no one buries the carcass.

Tonopah could have been one of the casualties. It started with a silver strike in 1900, grew and then declined, but mining never ceased altogether. With U.S. 95, it became a rest stop for travelers. And the Tonopah Test Range brought jobs that came and went with different development projects, like the Stealth Bomber.

Just to the north, construction began in 2011 on the Crescent Dunes Solar Energy Project.

“The solar plant was the last boom,” said Dennis Duniphin, 37, an Iraq war veteran and bartender at the Tonopah Liquor Co. “We had like 800 people renting out rooms here. People brought in mobile homes and fifth-wheels. NAPA Auto added trailer hookups in the parking lot.”

But once the project was built, all those welders and pipe-fitters left, and Tonopah cycled back into decline. The hospital closed in 2015, forcing residents to drive two hours to Bishop, in California, for medical emergencies.

When Duniphin graduated high school here in 2000, he had 55 students in his class. “Now it’s like five.”

He doesn’t think voters in Clark and Washoe understand how rural towns often hang by single threads. But he has hope.

“The lithium mine is taking off,” he said. “That’s the next big thing.”

He shares the largest of Nevada traditions — waiting for the next boom.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.