Bloomberg drops $124 million on ads in Super Tuesday states. Rivals go on the attack

DENVER — Democratic presidential candidate Michael R. Bloomberg has spent more than $124 million on advertising in the 14 Super Tuesday states, well over 10 times what his top rivals have put into the contests that yield the biggest trove of delegates in a single day.

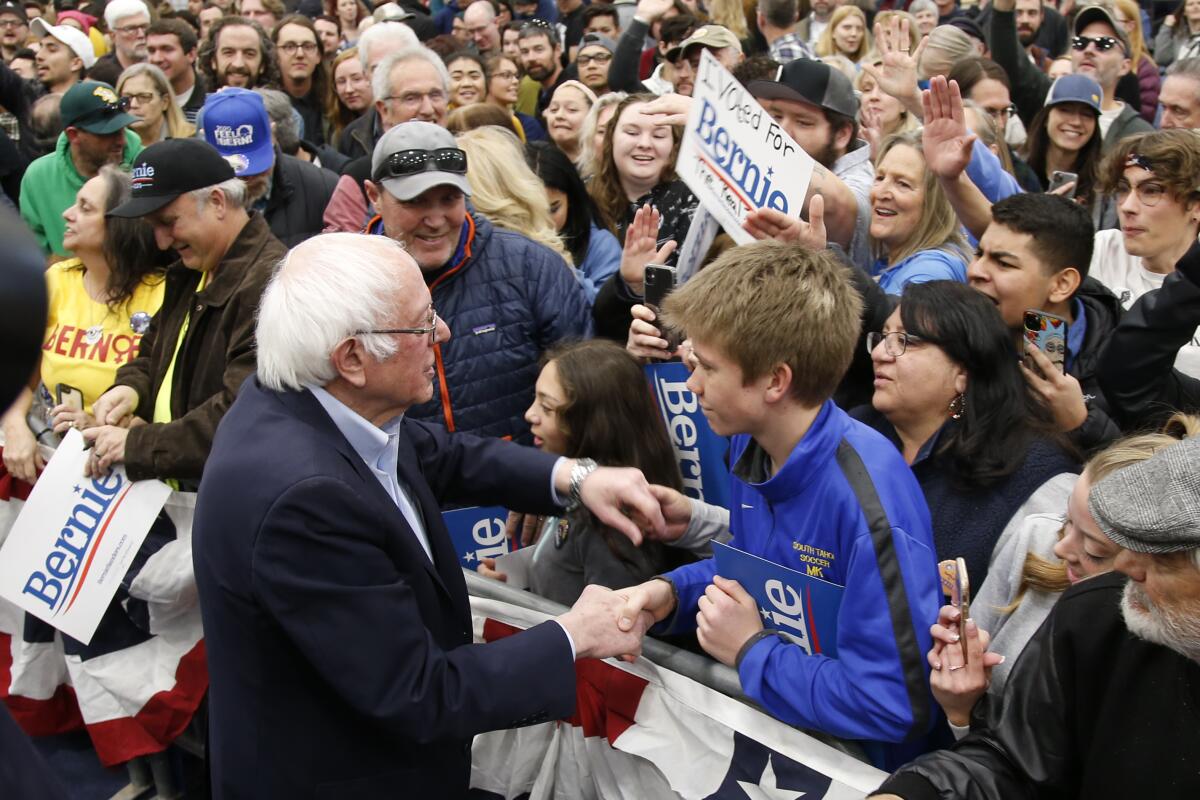

The only other candidate to advertise across most of those states so far is Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, who has spent just under $10 million on ads for the March 3 primaries.

Bloomberg, the former New York City mayor, has also poured millions into ground operations in Super Tuesday states. In Colorado, where voters already are casting primary ballots by mail, he has a paid staff of 55 people; Sanders has two.

For nearly three months, Bloomberg has been the only Democrat to devote most of his travel to those states, which include California, Texas and North Carolina. His opponents are still scrambling to gain traction in contests on Saturday in Nevada and Feb. 29 in South Carolina. Bloomberg is skipping those races, as he did earlier in Iowa and New Hampshire.

There will be 1,357 pledged delegates up for grabs on March 3; it takes 1,991 to capture the nomination.

Alan Abramowitz, a political scientist at Emory University in Georgia, said it was “very significant” that Bloomberg was banking so heavily on Super Tuesday, an unprecedented strategy that makes the biggest day on the Democratic calendar even more important than usual.

“It’s going to really reshuffle the race,” he said.

Former New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg will appear in Wednesday’s debate in Las Vegas, in a stark departure for the choreographed campaign.

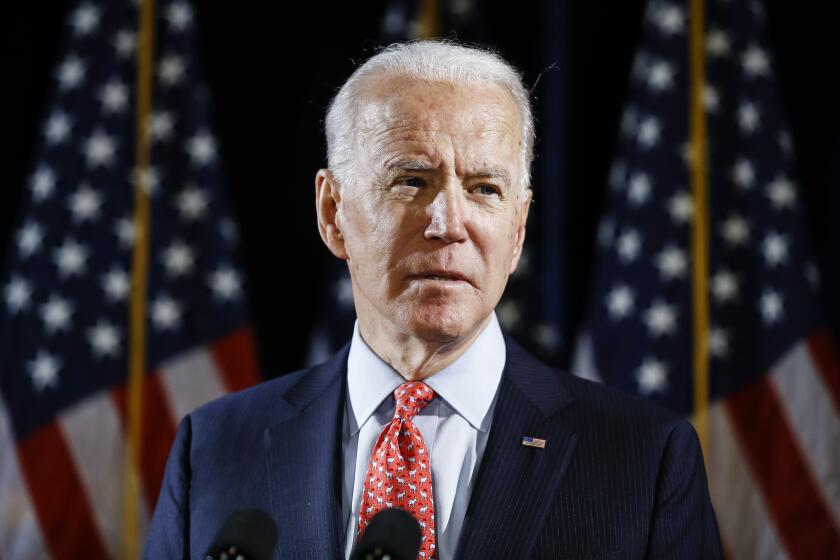

Bloomberg’s money is having an impact on the highly fluid Democratic race. He now ranks in the top tier, behind Sanders and former Vice President Joe Biden and just ahead of Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Ind., according to a Real Clear Politics aggregate of national polls.

Bloomberg’s rise has made him a prime target.

“Democracy to me means one person, one vote — not Bloomberg or anyone else spending hundreds of millions of dollars trying to buy an election,” Sanders told 11,000 supporters at a noisy rally Sunday night in Denver.

In an interview that aired Sunday on NBC’s “Meet the Press,” Biden attacked Bloomberg for defending police stop-and-frisk tactics during his 12 years as mayor. Bloomberg’s $60-billion personal fortune “can buy you a lot of advertising, but it can’t erase your record,” said Biden, who is counting on black voters in South Carolina to revive his faltering candidacy after dismal results in the mainly white states of Iowa and New Hampshire.

A week before launching his campaign in November, Bloomberg apologized for stop-and-frisk — six years after a federal court found the policy violated the rights of African Americans and Latinos.

Should Bloomberg qualify for the Democratic debate Wednesday in Nevada, opponents will likely challenge him on that and more. One of his big vulnerabilities is the allegation that he often made sexist and degrading comments about women at his New York financial firm.

For the most part, Bloomberg until now has been able to define himself on his own terms in a flood of ads introducing himself to millions of voters who knew little about him. He has stressed his record fighting gun violence and climate change. His core argument is that he’s the Democrat best suited to unseat President Trump in November.

In Colorado, Bloomberg has spent $5.5 million, and Sanders just under $500,000, according to Advertising Analytics, an ad tracking firm that provided data to The Times.

The pattern is similar in most of the other Super Tuesday states. In three of them — Virginia, Alabama and Oklahoma — Bloomberg is the lone Democrat on the air.

The most expensive state for ads is California, which awards 415 delegates on March 3, more than any other state. Bloomberg has spent nearly $41 million in California, and Sanders, $5 million, Advertising Analytics found.

Also advertising heavily in California is San Francisco billionaire Tom Steyer, who is stuck below 2% in national polls despite recent gains in Nevada and South Carolina. He has spent nearly $26 million on TV and radio spots. His absence of ads in the other 13 Super Tuesday states suggests he could be aiming to raise his profile in his home state for a future run for public office.

Much of what will shape Super Tuesday is outside Bloomberg’s control, above all the momentum that rivals will gain in Nevada and South Carolina.

Warren hopes to emerge in a stronger position to compete with Sanders for the party’s progressive voters.

Biden, Buttigieg and Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar are vying to consolidate the party’s moderates, posing a more direct challenge to Bloomberg, a centrist and former Republican. If Democrats rally behind one moderate by the end of February, that candidate could wind up dominating in states such as Colorado on March 3.

Biden, who has struggled to raise money, has hired a state director in Denver, but has yet to open any offices in Colorado; Bloomberg has nine. But voters already know Biden well, and his supporters include some of Colorado’s best-known Democrats, among them former U.S. Sen. Ken Salazar and ex-Denver Mayor Federico Peña, both one-time Cabinet secretaries.

Sanders, who trounced Hillary Clinton in Colorado’s 2016 caucuses, is relying on his strong grass-roots following.

“We’re looking good in Nevada and South Carolina, and with your help we’re going to win Colorado on Super Tuesday,” Sanders told the exuberant crowd Sunday in a Denver convention hall.

Thousands of his supporters have volunteered to knock on doors and make phone calls, said Tim Dickson, his Colorado field director.

Michael Bloomberg is rapidly rising in the polls, alarming rivals as he uses his personal fortune to break all the old rules of presidential campaigning.

For the first time in 20 years, Colorado is holding a presidential primary instead of caucuses, which tend to attract political activists. The 2016 Democratic caucuses drew just 123,000 voters, while the party’s 2020 primary is open to 2.4 million, including nearly 1.4 million independents who can sway the results in unpredictable ways.

“That’s a wild card,” said Alan Salazar, a Colorado Democratic strategist who is chief of staff to Denver’s mayor and is neutral in the primary. “I’m not sure any of us knows how that will shake out.”

Bloomberg’s Colorado offices include two in Denver — one in a former Patagonia store and another, its walls painted black, in a former vape shop next door to a marijuana outlet. Scattered on tables are “Colorado for Mike” signs and free Bloomberg T-shirts. Staff, who are better paid than on other campaigns, work on new MacBooks. Veterans of more cash-starved operations are struck by the abundance of resources.

“It’s on steroids,” said Tom Boyd, a Bloomberg field organizer in Denver. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

On Saturday, a couple dozen Bloomberg canvassers, both paid and volunteer, set out from his office in a Wheat Ridge strip mall in the foothills of the Rockies. Two of them, Brittany James and Allyson Gottesman, spent the next couple hours going door-to-door among the snow-covered lawns of the Denver suburb trying to drum up support for Bloomberg.

They found no one committed to voting for him. The closest they came was Cherice Chavez, 30, who told them she was torn between Bloomberg and Buttigieg.

“We want somebody who can beat Trump,” Gottesman told her.

“I do, too,” Chavez said. She knew Bloomberg was in finance but did not realize he’d been mayor of New York City.

A neighbor, artist H.R. Gerrard, told the canvassers that he was voting for Sanders, but would happily back Bloomberg if he’s the Democratic nominee. He stepped outside in his flip-flops and pointed to a frozen shrub.

“Right now,” he said, “I would vote for this dying rosebush.”

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.