What do the residents of South Bend, Ind., home to Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg, think of him? After decades of malaise, South Bend went through big changes during Buttigieg’s tenure as mayor.

SOUTH BEND, Ind. — It was Jacob Titus’ favorite running route when he trained for high school track: along the train tracks to the sprawling warren of machine shops, assembly lines and warehouses on the city’s south side, and then into the abandoned factories themselves.

Decades ago, these buildings whirred with activity — and none more so than Studebaker Auto Co., which had powered South Bend to prosperity.

Hollowed by decades of disuse, these factories were testament to the city’s decline. Titus couldn’t stay away.

“The scale — it’s just crazy. Just how big and empty and just completely dark,” he said.”They were very alluring.”

If Titus, 27, tried to revisit that route now, he’d run into a few obstacles. The Studebaker tool room is now home to South Bend City Church. The paint lab houses businesses including a biotech start-up and a coding school. The six-story assembly line, once most recognizable for its broken windows, is the anchor of a major commercial redevelopment project catering to the city’s burgeoning tech scene.

About this series

Presidential candidates spend most of their time on the road, campaigning from one town to another. But what is the America they see from their own front doorstep? In this series of stories, Times reporters explore the communities that shaped some of the top Democratic candidates and their campaigns.

It was there that Pete Buttigieg officially launched his bid for the Democratic presidential nomination.

No city has been as integral to the presidential campaign of its hometown candidate as South Bend has been to its former mayor. The 38-year-old, who has a far shorter resume than his rivals, presents his tenure as a proof point of his governing experience and vision.

But while most of the national coverage fixates on the yes-or-no question of “did Mayor Pete do a good job?” residents of South Bend have been grappling with a broader question that predates Buttigieg and will outlast him: What does it mean for a city to reinvent itself?

The lively downtown and sparkling parks are physical signs of change that are largely driven by government officials and business leaders. But many residents describe a deeper transformation — a collective exercise in building a new identity.

“I’m not here because buildings got renovated,” said Titus, a graphic designer and podcast host. “I’m here because there was a vision that I latched on to of what we could do here, and how I could be part of it.”

But in a city whose decline lasted decades, some South Benders can’t help but wonder whether this upturn will last. Change has made its way through town unevenly, with many in its black and Latino communities feeling left out.

“He’s had control over the narrative — that narrative has been ‘South Bend is back,’” Jorden Giger, an activist with Black Lives Matter, said of Buttigieg. “Well, how can South Bend be back when most working families here are struggling, when the school system is failing, when the black community is in dire straits?”

The mood, said Jason Miller, lead pastor of the nondenominational South Bend City Church, is just as complicated as its narrative.

“Right now,” he said, “I would describe it as hopeful, energetic — and tense.”

::

The mural painted on the Michigan Street footbridge is cheery and proud, welcoming motorists to South Bend with depictions of distinctive local architecture such as the Egyptian columns of the county courthouse and the teal archways at the entrance of a local emergency room.

When Buttigieg was a teenager, trudging past it on his way to St. Joseph High School, the bridge was mural-less and bleak, notable for its peeling paint and abundance of pigeon poop.

The rich, brainy city of Cambridge, Mass., reflects Elizabeth Warren’s have-a-plan approach as well as inequality issues at the center of her campaign.

“Part of the commute I dreaded as a 14-year-old was walking under that bridge,” Buttigieg said.

The comparisons of the South Bend of his youth and today come easy to Buttigieg, who lives blocks away from his childhood home. His current domicile is a large white Neoclassical-style house he shares with his husband, Chasten. The block is part of a local historic district; his house was built at the turn of the 20th century and others date back even further.

The homes all face the St. Joseph River, a central character in South Bend’s story. The banks of this Lake Michigan tributary were settled by the Potawatomi tribe, and later, European-descended fur traders. The city got its name from the river’s southernmost bend.

The river also provided power for South Bend’s industrial rise, a climb that peaked with Studebaker. The auto company was South Bend’s pride, a shorthand for its broader manufacturing prowess that included Singer sewing machines and Bendix brakes. The city swelled with middle-class workers, who could rely on a lifetime of solid work right out of high school.

Until Dec. 20, 1963, when Studebaker closed its doors for good, leaving thousands out of work and a city without its anchor.

The closure was a shared trauma that residents still speak of in horror-movie terms — the “disaster” or, simply and ominously, “the event.”

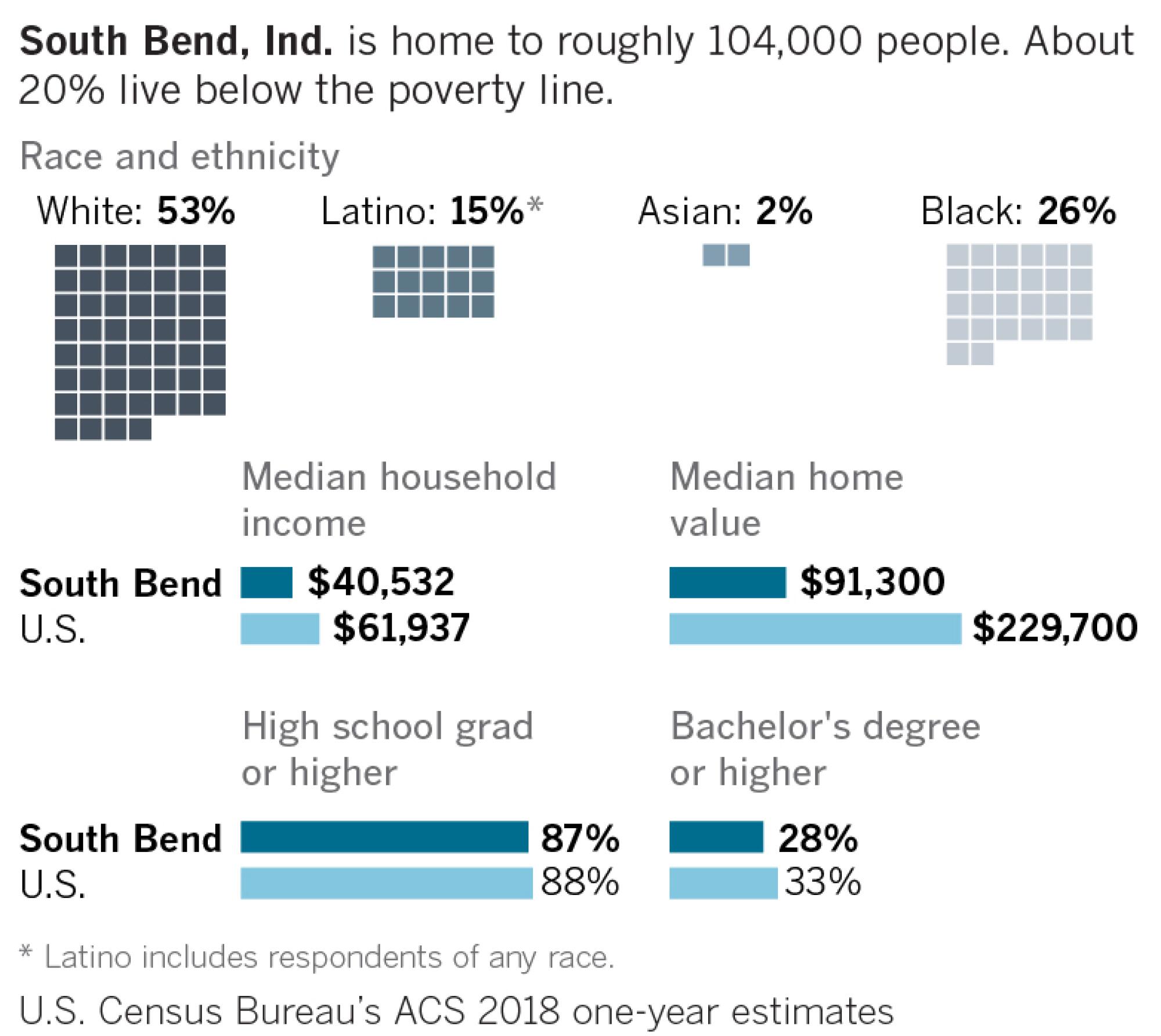

The city, which peaked at around 130,000 residents in the early 1960s, lost more than a quarter of its population; by 2010, it was around 100,000 people. Those who could afford it fled to the suburbs.

“People in the ’80s were still talking about, ‘Could a business like Studebaker get reinvigorated in this town?’” said Shane Fimbel, a tech entrepreneur whose grandfather worked for the auto company in the 1940s. “We were still in this hangover for a long period of time before it was just like, no, that’s really not coming back.”

South Bend was still slumping when Buttigieg was growing up. The son of two Notre Dame University professors, he and his peers absorbed the belief that the city’s best days were behind it.

“Growing up, certainly in my generation, [was] getting the message that success had to do with getting out of the city,” he said.

He left for Harvard University, then Oxford and finally a consulting job in Chicago. In his memoir, he describes moving home for the most prosaic of reasons: to save money on rent while he spent most of his time on airplanes as a consultant. He used South Bend as a base for a failed run for Indiana state treasurer in 2010, and a successful run as mayor in this heavily Democratic city the following year.

Between his two campaigns, a Newsweek article named South Bend one of America’s “dying cities.” To hear Buttigieg tell it, the story was a catalyst for the town’s turnaround.

“More than anything, it aroused or maybe injured a sense of pride that we didn’t know we had,” he said.

In reality, the city’s changing fortunes came in fits and starts. Notre Dame, the vaunted university that had long kept its distance, decided to engage more with its neighboring city, figuring South Bend’s success was crucial to attract the talent necessary to further its own ambitions. Buttigieg’s predecessor knocked down some of the abandoned Studebaker buildings, clearing the way for new developments in the old industrial zone. The robust recovery of the national economy added momentum to South Bend’s local growth.

“A lot of those seeds have been planted, even before Pete,” said Jeff Rea, president of the South Bend Regional Chamber of Commerce. “And then Pete sort of fertilized them and helped them grow.”

For some residents, the mere fact Buttigieg returned home has a powerful symbolic effect .

“It matters in terms of just setting a tone that this is a place you should come back to, and that you can chase your dreams here,” said Kevin Lawler, who worked on Buttigieg’s 2011 campaign and now owns a restaurant.

Miller counts himself among South Bend’s unlikely residents. A self-described “reluctant pastor,” he had plans to start a church in a flashier city. But South Bend’s affordability gave him freedom to experiment in building a faith community without needing to pack the pews to pay an expensive rent. He helped form the idiosyncratic South Bend City Church, with what he calls “litgurically promiscuous” practices.

“It’s like we put black gospel and Anglican high church and contemplative Quakerism all in a blender,” he said.

But because of its Studebaker location, the church is undeniably of South Bend.

“The thought that we could be located in a place that speaks of history and identity and relationship for the city was really desirable,” he said.

After decades of losing people, the city’s population has ticked up for five consecutive years to about 104,000 residents.

The city center, once a dead zone, hums with enough life that it can be hard to find parking — a phenomenon that sparks joy among residents. Just north, at Notre Dame, at least 70 start-ups have recently launched. In the industrial zone, engineers conduct research on turbomachinery for use in jet engines. And on the far northwest side of town, Amazon has set up distribution centers, taking advantage of South Bend’s proximity to major cities such as Detroit and Chicago.

“The city has a new lease on life,” said Fimbel, chief executive of Trek10, a cloud computing company. “It has been provided permission to believe that this is a place in the world where this can happen — it’s happened before and it can happen again.”

For Buttigieg, the personal landmarks of his hometown now seem inextricably entwined with his presidential bid. Next door to the Fiddler’s Hearth, the downtown pub where he and Chasten had their first date, is a whitewashed wall blaring “South Bend for Pete” in the style of his campaign logo. His frequent breakfast spot, Peggs, sits down the block from his campaign headquarters. Chico’s, a Mexican restaurant on Western Avenue, is the backdrop on the cover for his memoir.

An unofficial fan site details a South Bend walking tour of “all the important Pete spots,” curated with an aficionado’s scouring of Buttigieg media appearances. Among them is the Studebaker fountain, an ornate Edwardian-style electric fountain that was gifted to the city in 1906 by John M. Studebaker, co-founder of the auto company, as a symbol of the grand ambitions of both the manufacturer and its hometown.

By the 1940s, the fountain had fallen into such disrepair that it was dismantled. It was restored and dedicated last fall in its new home — in a park across the river from Buttigieg’s house.

“The re-dedication of the Studebaker fountain is kind of like putting the cap on the Studebaker story,” said Mike Keen, a sustainable developer who taught sociology for 30 years at Indiana University South Bend. “We’ve restored history and we’re moving on.”

::

The fountain is one landmark in the city’s Near Northwest neighborhood. Another is a preposterously large Adirondack chair — cherry red and roughly 15 feet high. Keen cobbled together about $1,800 for the project; micro-improvements of this type are sprouting all around town.

The chair’s whimsy belies the thorny reality of the environs it sits in. Near Northwest, which is about a mile from Buttigieg’s home, was built at the turn of the 20th century as the city’s industrial workforce began to swell. It was home to a flourishing upper-middle class, many of whom fled to the suburbs after the factories closed. By the 1980s, crime was high, vacant houses were common and its reputation had congealed as “troubled.”

Now the chair sits on Portage Avenue, what Keen calls a “bellwether street” of the neighborhood, its dividing line. The area toward the river is a more affluent collection of meticulously preserved historic homes. In the other direction, renters outnumber homeowners living in bungalows and simple two-story houses with thatches of neat front lawns. Interspersed every so often are completely empty lots that stand out like missing teeth — the result of Buttigieg’s “1000 Homes in 1000 Days” initiative to rehab or knock down blighted properties. Forty percent of the neighborhood’s residents live in poverty.

“It’s the best of all the neighborhoods in the city and sometimes the worst of all the neighborhoods in the city,” said Kathy Schuth, executive director of Near Northwest Neighborhood Inc., which develops affordable housing. “And maybe South Bend in general feels this way — it’s often a tale of two cities. Those with means experience the city in an entirely different way than those without means.”

Such is the complicating factor in South Bend’s revival. The heady sense of possibility in some quarters feels much fainter in others. The black poverty rate in South Bend is twice the national rate, according to a report put out by Buttigieg’s administration; Latino poverty is 10 percentage points higher than the average nationwide.

“It would be nice to see more focus on just the neighborhoods,” said Paul Beltran, a case manager at a local clinic who moved to South Bend as a child.

There have been some improvements beyond downtown, he acknowledged. The city redid the streetscape of Western Avenue, which is lined with Latino businesses, and supplied a grant to spruce up the façade of a popular ice cream store there.

“That was critical. But that’s what we on that side of town needed as a start-up,” he said. “That was something to make sure that people don’t feel like we’ve been forgotten.” Now he wants to see more.

Gladys Muhammad, a veteran of the city’s fair-housing battles, said discernible change has come to minority communities, be it more money for a park in the west side of town or the symbolism of renaming a major thoroughfare after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. She credited Buttigieg’s administration for being willing to talk about inequities in the city.

“A lot of issues that over the years we have glossed over, they’re on the table now,” she said.

Burlington shaped Sanders as Sanders shaped Burlington, so much so that it’s hard to consider one without the other.

That’s hardly satisfactory for younger activists like Giger, 28, whose group has followed Buttigieg across the country calling attention to the strained relationship between African Americans and South Bend police under his tenure.

Downtown may be flush with cranes building luxury condos, Giger said, but prices there are out of reach for many black residents. High-paying tech jobs, he said, are unattainable for many in a city where roughly 70% of residents don’t have a college degree.

“We’re effectively being locked out,” he said.

Buttigieg acknowledged that inequality remains a top issue in the city.

“I think the unfinished biz of this recovery — that we’ve made progress on but haven’t done enough — is making sure that prosperity reaches everybody,” he said.

::

The glare of the presidential campaign has intensified that swirl of frustration and fragile hope, as locals hash out their competing assessments of their ex-mayor on a national, and even international stage.

“It’s made it a little bit harder to have some productive family conversations when it’s not just family that’s watching,” Miller said.

But South Bend’s story is a fitting test case in a Democratic presidential primary that is, in one sense, a battle over conflicting visions of change. None of the candidates has actually navigated a community through change as recently and as directly as Buttigieg. And in South Bend, reinvention has not been a wholesale revolution.

“We’re acutely aware we can’t boil the ocean,” said Bryan Ritchie, who leads the IDEA Center, an innovation hub at Notre Dame. “This is going to have to be something where we have to start small and let it ripple out.”

For Buttigieg’s detractors, the city’s changes speak to his moderation that they say fails to meet the urgency of the times. His allies see it differently: an ambitious agenda broken up into digestible chunks.

“It’s not incrementalism in that it’s small solutions that you hope, over time, add up into a thing,” said Dustin Mix, a co-founder of the start-up incubator Invanti. “But it’s more of this idea of, how can we navigate big change honestly and intelligently?”

Buttigieg left office in January with his city’s rebirth still a work in progress, as residents wait to see if the influx of new money and people solidifies into something that lasts.

It can be exhilarating and exhausting for people like Schuth, whose Near Northwest neighborhood balances on the tipping point of success. But at the very least, she said, the conversations in her city have fundamentally changed, from, “Hey, we’re a city in decline, and at what point do we pack up and give up?” to “Hey, we’re a city that’s beginning to rebuild.”

“It’s the difference between feeling like you’re putting a cork in a dam that’s busting,” Schuth said, “and building a new dam.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.