2020 Democrats struggle to narrow the field as New Hampshire prepares to vote

MANCHESTER, N.H. — Democrats’ hopes that New Hampshire voters might bring clarity to the chaotic fight for their party’s presidential nomination were fading Monday as the state’s primary election neared, with the wide swath of voters seeking a moderate candidate continuing to resist coalescing behind any one contender.

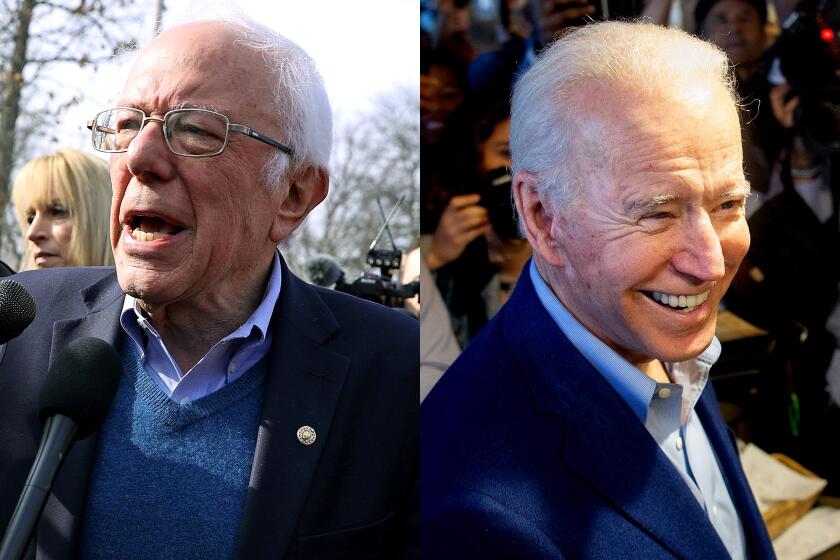

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders closed out his New Hampshire campaign before a crowd of thousands at the University of New Hampshire, illustrating the support from young voters that has propelled him to the lead in polls here. Sanders’ lead among voters on the party’s left appears to have boxed out Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, according to multiple polls of New Hampshire voters.

As voting here approached, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Ind., continued to joust for position as the main centrist alternative to Sanders, raising the likelihood that the contest will continue long after candidates exit the state.

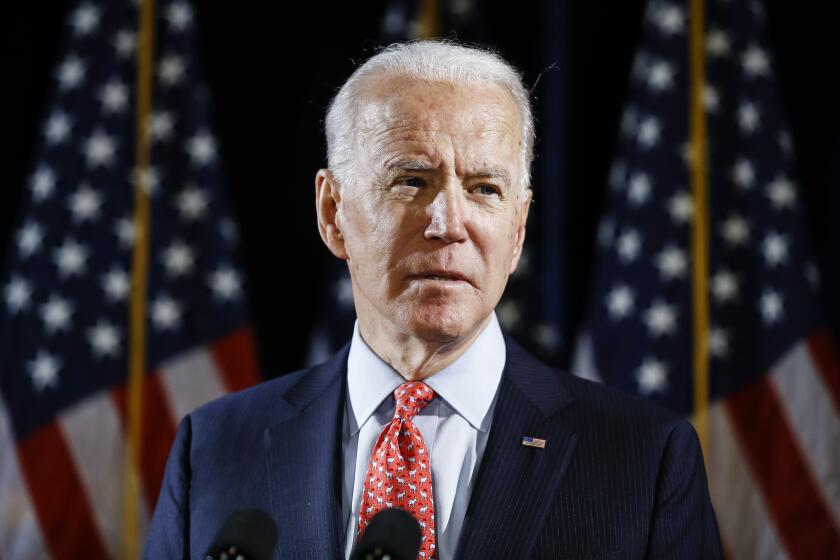

Former Vice President Joe Biden, by contrast, continued to struggle. The overall race for the nomination “is just getting started,” he said in an interview Monday on CBS’ “This Morning.”

But a prominent Biden supporter all but conceded the state.

“New Hampshire is going to be tough,” Bill Shaheen, a longtime Democratic activist who is married to Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, said in an interview. “But we will go on. This race isn’t over just because of New Hampshire.”

Biden’s plunge in support in the days leading up to Tuesday’s primary here has left the moderate lane wide open to other candidates, including former New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg. He skipped this state, but a national poll released Monday by Quinnipiac University showed him moving into a rough tie with Biden among Democratic voters nationwide, with Sanders leading both of them.

The former vice president has sought to downplay the importance of New Hampshire and its heavily white electorate.

“Nothing is going to happen until we get to a place — and around the country — where there is much more diversity,” he said.

Later, speaking to about 100 people in a church basement in Gilford, he steered clear of criticizing his rivals, focusing instead on President Trump, who arrived here Monday evening for a rally.

Trump plans to run on the healthy economy, and Biden told voters he was the best candidate to counter that pitch.

“He’s telling the American people they should accept a devil’s bargain — that it’s OK to sell the soul of this nation just to help a few very, very wealthy people,” he said.

But the bulk of the job growth in the country happened before Trump took office, Biden said.

“Guess where he got that good economy from? The Obama-Biden administration.”

Trump, in a message on Twitter, made clear that his rally plan was in part an effort to troll the opposition.

“Want to shake up the Dems a little bit — they have a really boring deal going on,” Trump wrote in a post that jibed at the Democratic candidates and their Iowa caucuses meltdown of last week.

During an evening rally in Milford, Buttigieg said “the president of the United States thinks we’re suckers” — pointing to administration proposals to cut programs Trump had said he would protect.

“Did you see the budget he put out today?” Buttigieg said. “Cuts to environmental protection, cuts to public education. He’s already said that Social Security is fair game and on the table. Undermining Medicare, cutting Medicaid.”

“But we know, we know, that there will be accountability for all of those broken promises.”

Trump narrowly lost this state in the 2016 general election, and his campaign has targeted it as one that potentially could be flipped in 2020 and whose four electoral votes could make the difference in a close race.

The night before his arrival, Trump’s supporters began pitching tents outside the arena where he is scheduled to speak. Their enthusiasm contrasted with the anxiety pervading Democratic ranks.

Centrist Democrats here have been bouncing among a cluster of candidates. Many have gravitated toward Buttigieg, but tracking polls suggest his momentum may have stalled over the weekend as his rivals pounded away at him, with Biden in particular questioning his experience and fitness for office.

Over the weekend, Klobuchar moved into position for a strong showing. The tracking polls showed her edging into a possible third place behind Buttigieg and Sanders.

“We can’t be sure because tracking polls are a quick snapshot of where voters are,” said David Paleologos, the director of the Suffolk University Political Research Institute, which runs one of the surveys. “Is it a spike that will come back down, or is it a continuation?”

Five other major candidates — Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet, Rep. Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii, former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick and two wealthy businessmen, Tom Steyer and Andrew Yang — will also appear on the ballot, but the bulk of voter attention has focused on the top five.

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

Both Klobuchar and Buttigieg appealed to moderate voters in part by criticizing Sanders.

At a Rotary Club in Nashua, in the vote-rich southern part of the state, Klobuchar reminded the audience that in Friday’s debate, she had been the only candidate willing to raise her hand and say that Democrats would be making a mistake to nominate a candidate who calls himself a democratic socialist.

“That doesn’t mean I’m not good friends with Bernie; I am,” she said. “I just have a different philosophy than he does and a lot of it is grounded in a respect for entrepreneurship.”

Buttigieg, at a rally in Plymouth, a small city in central New Hampshire, said that while “I respect his intentions,” the Vermont senator was making promises he would be unable to keep without tax increases on the middle class.

“Look at Sen. Sanders’ math — $25 trillion worth of revenue” over the next 10 years, much of it in new taxes to pay for healthcare, Buttigieg said. Some of those taxes, including higher levies on the wealthiest Americans, “we can agree on,” he said.

“But here’s the problem, there’s $50 trillion worth of spending. So about half of it is unaccounted for, and there’s no explanation for where the other $25 trillion is supposed to come from.”

“Are we going to pay for it in the form of still further taxes? Or are we going to pay for it in the form of broken promises?”

An American majority exists for major, progressive change, he said, but not “if we take it all the way to the extreme.”

Sanders has said in interviews that he does not believe voters expect him to lay out a complete accounting of taxes and spending at this stage of the campaign.

A key to the result for both Buttigieg and Klobuchar likely will be independent voters, who are allowed to participate in the Democratic primary here.

Non-party voters likely will make up more than 40% of the turnout Tuesday. In 2016, independents delivered the lion’s share of their votes to Sanders as he competed against Hillary Clinton, who was the choice of establishment Democrats.

Many of the state’s independent voters, however, are politically moderate. Biden has little support among them, and if they swing heavily behind either Buttigieg or Klobuchar, they could have a major impact. They also tend to be late deciders.

Midwestern moderates Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar are making a strong case against the liberalism of Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders.

Warren, who has struggled to keep pace with Sanders among progressive voters, directly addressed Democrats’ angst about the difficulty of beating Trump — and their reservations about her own electability — as she made her closing argument before a capacity crowd at the Rochester Opera House, saying she had faced adversity before and refused to give up.

“This is about winning unwinnable fights,” she said. “People think that folks with the money are always going to win. They don’t know what they are up against. It’s the folks with persistence who are going to win.”

The frenzy of activity once again revealed why Sanders remains such a force in his neighboring state and nationwide. The 78-year-old avoids taking questions and limits his interaction with voters, sticking to talking points he has echoed for years. But his events are consistently packed. And voters who show up at them tend not to be wavering or candidate shopping. They are all in for Sanders.

For his closing rally, Sanders packed a University of New Hampshire arena that seats 7,500, luring supporters with a concert by the Strokes and an energetic appearance by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York.

The attendees cheered Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez as loudly as they cheered the music, waving “Bernie” signs and erupting with noise as Sanders recited his now-familiar promises, including free healthcare for all, a big boost in the minimum wage, equal pay for women and free public college.

“Why Bernie?” Ocasio-Cortez asked the crowd. “Bernie has not committed to what is right when it was popular. Sen. Bernie Sanders has spent his entire life fighting for the right thing when it was unpopular.”

“Now people think progressive ideals are in vogue. Who put them in vogue? Bernie Sanders.”

Sanders’ followers staff a campaign infrastructure that is unmatched in New Hampshire. The campaign says its volunteers and staff knocked on 150,000 doors just on Saturday, reaching one out of every five voters in the state. Sanders campaign volunteers have visited more than 700,000 households this election cycle, the campaign says.

Sanders celebrated that aspect of his campaign when his time came to speak at the rally.

“This turnout tells me why we are going to win here in New Hampshire,” he said, boasting that the crowd was at least three times larger than any other candidate had drawn. “Why we are going to win the Democratic nomination.… We are going to win because we have an unprecedented multigeneration, multiracial grass-roots movement of millions of people.”

Halper reported from Rindge, Mason from Gilford and Engelmayer from Keene. Times staff writers Janet Hook in Rochester and David Lauter in Manchester contributed to this report.

Here are key dates and events on the the 2020 presidential election calendar, including dates of debates, caucuses, primaries and conventions.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.