How Lindsey Graham and the Republicans learned it’s Trump’s GOP now

WASHINGTON — Even as the Senate grapples with the third impeachment of a president in the nation’s history, ask a Democrat or Republican in Congress about Lindsey Graham, the South Carolina senator who’s become one of President Trump’s most aggressive defenders, and they’ll likely start with a laugh.

Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) recounted a congressional trip overseas in which Graham took a sleeping pill too late in the flight and was struggling to stay awake when his turn came to ask a foreign leader a question.

“He’s totally zonked out,” Collins recalled, chuckling, as protesters shouted at her to vote to remove Trump. “Lindsey asks a question along the lines of: ‘Is it fun being president?’” The whole room laughed, and Graham quickly recovered, shooting off a serious query.

Sen. Joni Ernst (R-Iowa) described how Graham welcomed her to the Senate: With a castration device, a reference to her 2014 campaign video touting her experience on a farm castrating hogs. Ernst says she keeps it in her office in the Capitol as a reminder to maintain good humor even in “the darkest and scariest of times.”

“That’s what he’s so good at,” Ernst said. Still, she allowed, Graham can embody a “sharp contrast.”

“When we need it the most — he doesn’t have to dig deep for this, it’s bubbling at the surface — he can flip a switch,” she said, “and be the most scathing, on-target adversary that Putin, or Al Qaeda, or name X, Y, Z terrorist, will ever face.”

With the impeachment trial underway, the characteristically affable Graham has increasingly directed his fire at domestic antagonists, the president’s Democratic opponents. He clearly relishes his role as Trump’s attack dog, whether on Supreme Court nominees or the impeachment articles centered on his actions toward Ukraine. And that role will take on even more prominence this week, as senators begin questioning lawyers for the two sides amid a heated debate over witnesses brought to a boil by new allegations from John Bolton, Trump’s former national security advisor.

“You can say what you want about me, but I’m covering up nothing,” Graham said last week, in one of a number of heated news conferences as House impeachment managers laid out their case. “I’m exposing your hatred of this president to the point that you would destroy the institution.”

Hours later, however, off-camera in a Capitol corridor, Graham ran into Rep. Adam B. Schiff, (D-Burbank), the lead manager and one of Trump’s favorite targets, who had just laid out the case against the president.

“Good job,” Graham told Schiff, shaking his hand. “Very well spoken.”

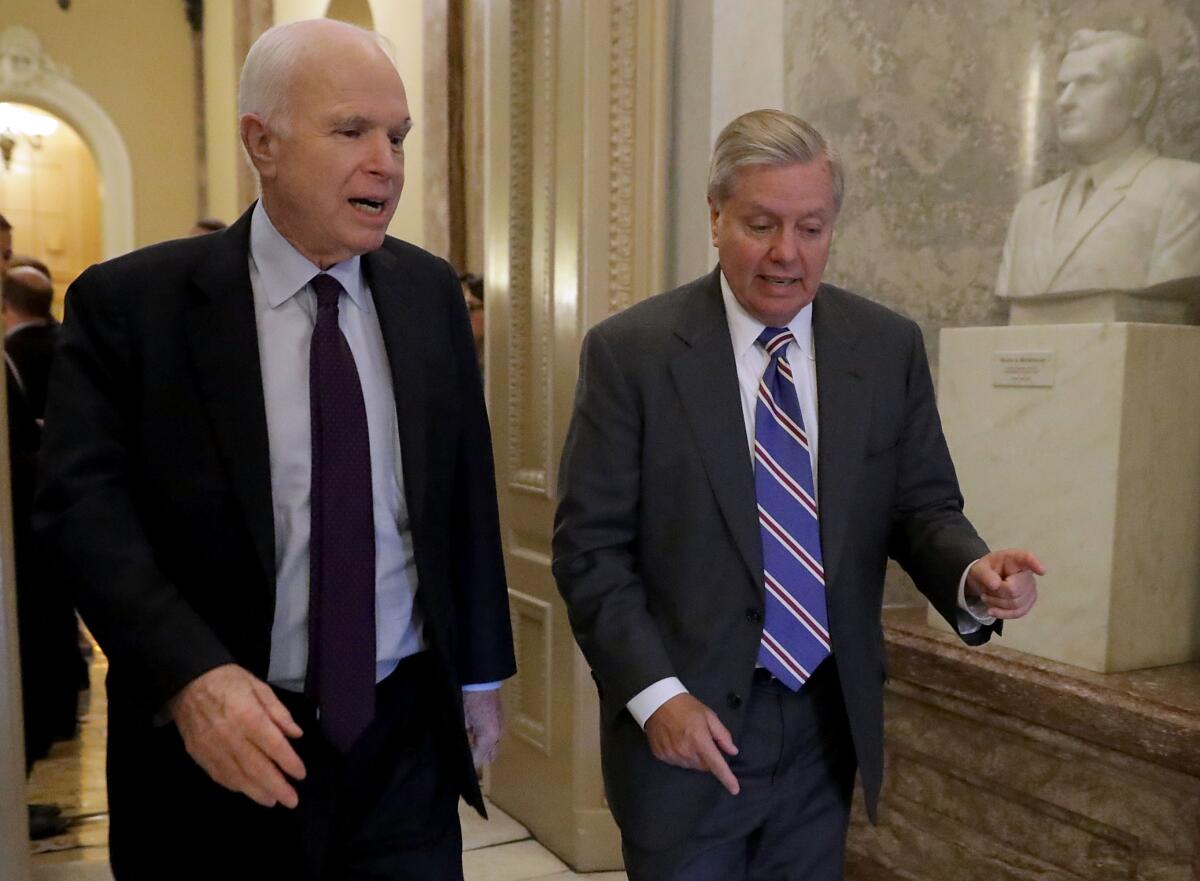

Over decades, Graham has painstakingly built a reputation in the Washington establishment as a national security leader willing to buck political convention on at least some issues — in the style of his longtime mentor Sen. John McCain of Arizona, who died in August 2018.

As he seeks a fourth term this year, however, he’s all but dropped his bipartisan bonafides on heated issues like immigration to double down on Trump-flavored appeals to the Republican base. Ahead of the 2020 election, Graham has now staked his legacy on an infamously mercurial president.

His transformation helps explain why Senate Republicans have remained so unified behind Trump. Despite polls showing the country as a whole closely divided on impeachment, that’s not the case in deep-red states like South Carolina. The cold reality for Graham and other ranking Republicans is that Trump is far more popular back home than they are.

When Trump was elected, many Republican officials thought they were the party and he, a newcomer to the GOP, was the interloper. Instead, they’ve learned a hard lesson: It’s been Trump’s party all along.

Graham declined a request to be interviewed for this article.

Trey Gowdy, the former South Carolina congressman, and a Trump defender, explained Graham’s calculation as realpolitik.

“I do get the national narrative that they think he is somehow becoming this sycophant-ish disciple of President Trump,” Gowdy said. “But it’s about having a relationship where you can go express those differences. If you don’t have a relationship, you can’t be heard at all.”

John Weaver, a longtime McCain advisor, doesn’t buy that “adults in the room” defense. “Imagine if you were a passenger on the Titanic, then, after the ship hit the iceberg, you handcuffed yourself to the railing and threw the key into the ocean,” Weaver said. “That’s the danger for them; they’ve handcuffed themselves to this man, to Trump.”

It was during the country’s last impeachment, of President Clinton, that Graham first met McCain, forging a long friendship. McCain said he was “so impressed” by Graham’s performance as one of the House managers in the 1999 Senate trial that he quickly asked the then-congressman to back him for the Republican Party’s nomination in the 2000 presidential election.

“I said, ‘Look, I’d appreciate it if you’d help me in the campaign,’” McCain recounted in 2016 as he returned the favor by campaigning for Graham in New Hampshire during Graham’s quixotic presidential bid that year.

“I said sure,” Graham added, “and he said, ‘Why were you so quick?’ and I said, ‘Nobody’s ever asked me before.’”

The impeachment of a president, Graham quipped, is “a hell of a way to meet somebody.”

In the 2016 campaign, he was an outspoken critic of candidate Trump, alongside McCain. They presented themselves as the Republican establishment’s hawkish answer to Trump’s “America first,” isolationist foreign policy.

“I wasn’t a friend to Donald Trump,” Graham allowed Friday.

Four years later, Graham is a shadow member of his official defense team. He’s used his Senate Judiciary Committee chairmanship as well as his foreign policy credentials to push unproven theories about former Vice President Joe Biden and his son Hunter’s work in Ukraine, seeming to reverse himself on whether they should be called to testify. He faces tough scrutiny as a result.

“I’ll be watching with interest to see how he manages the next few weeks,” said Newt Gingrich, who was forced to resign as House Speaker in the face of a Republican rebellion in 1998 first engineered, in part, by Graham. “He has the potential to help frame exactly what’s going on.”

In 24 hours of arguments last week, House managers made their case for Trump’s removal by appealing to Republicans’ sense of patriotism and national security concerns. To bolster the case, they showed multiple video clips of McCain, a champion for Ukraine and its fight against Russian incursion, and of Graham himself, defending a broad theory of what’s an impeachable offense during the Clinton trial.

“I think I’ve aged, I think I’ve lost hair, I think I look 15, I think it’s fair game,” Graham said of the strategy. “I still believe it … I believe that high crimes and misdemeanors can literally be anything people want it to be.”

At the same time Graham enjoys the influence he’s earned by cultivating a proximity to the president, he likens his position as Trump’s close advisor to both a salesman and baby-sitter.

The latter task comes to the fore most often on foreign policy. Just hours before the House impeached Trump last month, Graham held a briefing for a small group of reporters to talk about a recent trip to Pakistan and Afghanistan. Asked whether leaders had expressed concerns that Trump might become more unpredictable after his impeachment, or whether he had his own concerns, Graham answered, “Well, to me, predictability is important.”

He pointed to the fallout from the president’s sudden announcements of withdrawals of U.S. troops from Afghanistan and Syria, which he had slammed as a “disaster in the making.”

“To say otherwise would be naive,” he said.

Sen. Jack Reed, (D-R.I.), whose work with Graham dates back decades, noted that the “very few times” that the senator has been willing to criticize Trump, “it’s at times that revolve on a foreign policy issue.”

Graham has had to fight his way into Trump’s inner circle, and to hold his ear on national security questions. When some of Trump’s other prominent defenders, including Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.) and Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), broke with the president over the missile strike that killed Iranian Gen. Qassem Suleimani, arguing it was an affront to Congress’ authority to declare war, Graham said his dissenting colleagues were endangering the United States.

Paul responded that Trump’s non-interventionist instincts are genuine, but he remains surrounded by “a lot of people who still think the Iraq war was a good idea.”

In Graham’s race for reelection — shaping up to be the most expensive contest in the state’s history — he faces a well-funded Democratic opponent, who’s attempted to use his role in impeachment to turn voters.

In South Carolina, however, Graham’s bigger concern has been keeping the Republican base behind him. He credits Trump in part for his recently improved popularity with the Republicans back home.

In return, he’s counseled the president to lay off Twitter, keep his distance from the trial and allow the Senate process to play out.

Asked Friday what advice he had for Trump, Graham deadpanned: “Go play golf.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.