In 2020 primary, beating Trump outweighs local loyalties for New Hampshire Democrats

CLAREMONT, N.H. — When Paul Tsongas won the New Hampshire Democratic presidential primary in 1992, his victory in the year’s first such contest was met with shrugs, overshadowed by the strong second-place finish of rival Bill Clinton.

Then and since, it’s been a political truism that candidates from New England have a decided edge in New Hampshire’s party primaries among voters in the compact region. Tsongas, then a Massachusetts senator, got little mileage out of his win because it was predictable. The so-called comeback of scandal-tarred Clinton, Arkansas’ governor, was not.

For the record:

10:50 a.m. Jan. 26, 2020An earlier version of this article said Michael S. Dukakis was a Massachusetts senator. He is a former governor of the state.

Things are different here now. The New England advantage is one more assumption that’s being challenged in this turbulent election cycle. Democratic voters seem to care less about whether candidates share their local sensibilities than about whether the contenders can beat President Trump.

Neither Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, who walloped Hillary Clinton in the 2016 New Hampshire primary, nor Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts is running away with the New Hampshire vote. Polls show they are bunched in a top tier with Pete Buttigieg, the former South Bend, Ind., mayor who emphasizes his roots among coveted working-class voters in the industrial Midwest, and former Vice President Joe Biden, a Democratic establishment favorite from Delaware by way of Pennsylvania.

“People are thinking outside our borders for once, and really looking for who can go toe to toe with the president,” said Jay Surdukowski, a Concord attorney heavily involved in Democratic politics. “There is a lot of strategic thinking.”

“I have heard the nouns Michigan, Wisconsin and Ohio more than I ever have in my life,” he added, referring to three crucial states Trump won in 2016, and Democrats are determined to deny him this time. “There is real concern about how some of these candidates would play in the Rust Belt and Middle America.”

The race for the Democratic nomination in New Hampshire’s first-in-the-nation primary is one of the most competitive in years. Rivals often mention the home-field advantage Warren and Sanders have, if only to temper expectations for themselves. Yet voters say candidates’ electability matters far more to them.

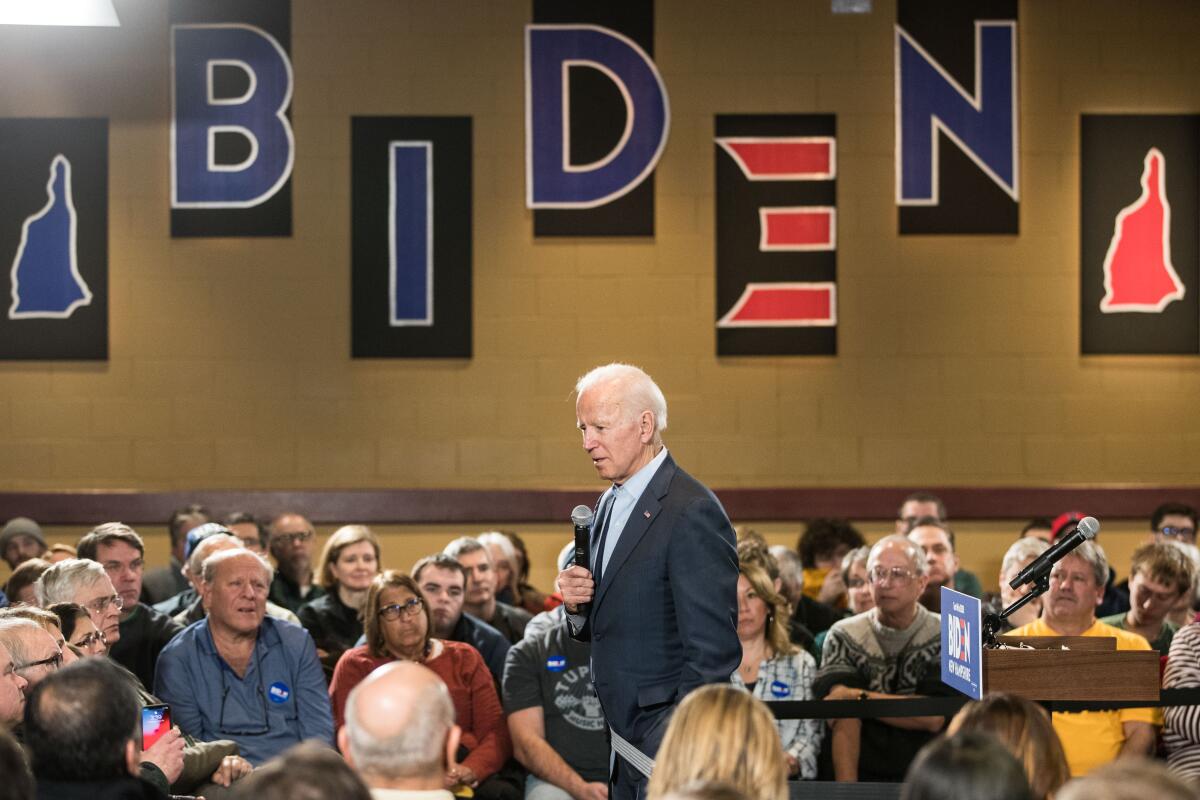

“I don’t think geographically there is any advantage this time around,” said Dorothy Connelly, an undecided retiree who attended a Biden event Friday in Claremont, a town on the Vermont border. “People are just so concerned. They want to make sure we beat Trump. For me, it is someone who can first and foremost unite the country.”

The preoccupation with electability partly explains why Sanders is losing some of his 2016 supporters — like Truman Breshears, another retiree who attended the Biden event.

“I am afraid Bernie might not beat Trump,” said Breshears, who is leaning toward Biden. “Biden is the one they are saying has a good chance.”

New Hampshire voters’ less parochial outlook also reflects changes in the way voters get information.

“There used to be a home-court advantage here because that is who you knew. And now, with social media, it is no longer all about local news. These people make national news,” said Luke Gorman, who attended a Sanders event Friday at Colby-Sawyer College in New London, where supporters Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield scooped free servings of their famous Ben and Jerry’s Cherry Garcia ice cream with actress Susan Sarandon.

The shift comes amid a primary campaign that has been nationalized more than any in recent history. Beyond the urgency Democratic voters feel about expelling Trump, those in New Hampshire are adjusting to a campaign calendar that has limited the time candidates can spend here and focus on their local concerns.

The hunt for small donors and support in national polls, two criteria for qualifying for the Democratic debates, has tied down the presidential hopefuls elsewhere. Also, with the decline of the local media’s influence and campaigns’ emphasis on online platforms to spread their messages, there is less reliance on face-to-face encounters and freestyle town halls best represented by the late Sen. John McCain’s “Straight Talk Express” bus tours of the 2000 and 2008 primary races.

“You are not seeing that ‘come at me with whatever you got’ style of campaigning this cycle,” said Scott Spradling, a New Hampshire media consultant. “It is a lot more careful, a lot more scripted.”

The idea of a New England home-field advantage dates to at least 1972, when the current nominating system began. Since then, there have been nine major candidates in the New Hampshire Democratic and Republican primaries who came from neighboring Maine, Massachusetts or Vermont, according to an analysis by FiveThirtyEight. Six of the nine won their party’s primary, three came in second. Former Sen. John F. Kerry and former Gov. Michael S. Dukakis, both Massachusetts Democrats, as well as Mitt Romney, former GOP governor of Massachusetts, each went on to capture his party’s nomination.

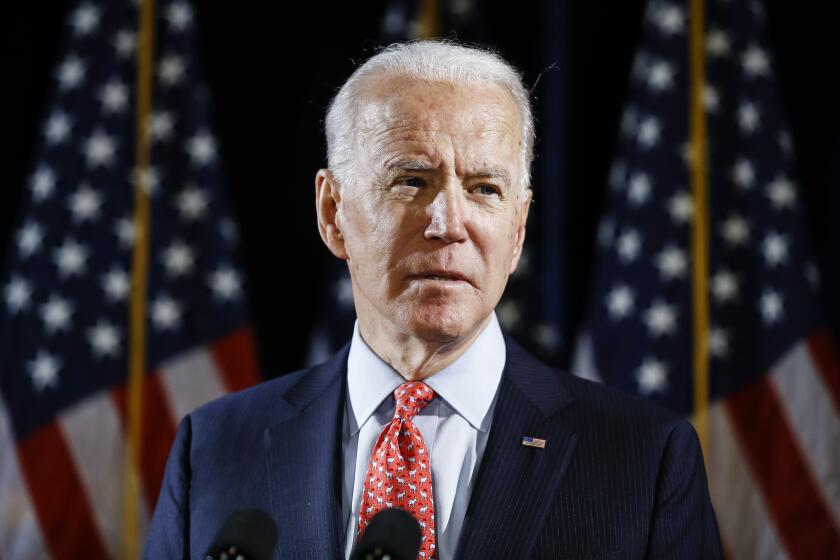

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

The affinity for a local comes naturally in a small region whose six states have a shared history back to Colonial times and much in common culturally.

“The Democratic voters in New Hampshire are very similar to the Democratic voters in Massachusetts or Vermont or Maine. It’s the same media market, the same economy, the same backgrounds, the same education levels. The voters here are largely the same as in your home state,” said Andrew Smith, a professor of political science at the University of New Hampshire.

The extent to which that gives a particular candidate a boost is a matter of long-running debate here. Neil Levesque, director of the New Hampshire Institute of Politics, argued that it is mostly a coincidence. New Hampshire voters aren’t inclined toward a candidate just because that person lives nearby, he said. Rather, “Massachusetts is a breeding ground for some really good candidates.”

Still, it is undeniable that the proximity gives neighboring-state candidates some logistical advantages. With the Boston area and populous southern New Hampshire sharing television and radio markets, Massachusetts politicians in particular get media exposure that gives them higher name recognition and greater familiarity than rivals from another region. The volunteer forces they have built up for their previous races are at the ready to parachute over the state line to knock on doors and help swell the crowds for candidate events.

“People in New Hampshire see these candidates more often and they have more experience with them during the year when it’s not political season,” said Bill Shaheen, a longtime political activist married to New Hampshire Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, a Democrat. He said of Warren and Sanders, “Elizabeth has come up and campaigned for candidates like my wife. There is genuine affection for Elizabeth and Bernie.”

“But,” Shaheen added, “most people in New Hampshire are going to think this out and make their decision by their head, not their heart.” Just last week he endorsed Biden.

Shaheen considered endorsing Sen. Michael Bennet of Colorado, a long-shot Democrat, but chose Biden because, Shaheen said, “he is the candidate who can beat the devil out of Donald Trump and help carry the Senate.”

However New Hampshire voters ultimately settle on a candidate, Spradling said that looking to the past for clues may be a fool’s errand this cycle.

“We are,” he said, “in a unique time.”

Here are key dates and events on the the 2020 presidential election calendar, including dates of debates, caucuses, primaries and conventions.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.