U.S.-Iran turmoil scrambles Democrats’ 2020 race, shifting focus to war and peace

WASHINGTON — President Trump’s order for the targeted killing of a top Iranian general and Iran’s quick retaliation have scrambled the 2020 campaign, thrusting issues of war and peace to the center of a contest that so far has been dominated by domestic issues.

Iran’s launch of more than a dozen ballistic missiles against a U.S. military base in Iraq on Tuesday night guarantees that the political fallout from the killing of Gen. Qassem Suleimani will not fade any time soon.

“What’s happening in Iraq and Iran today was predictable,” former Vice President Joe Biden said at an event in Philadelphia as news of the attack broke. “Not exactly what’s happening but the chaos that’s ensuing,” he said, faulting Trump for both his past action — abandoning an international nuclear deal with Iran in 2018 — and his more recent decision last week ordering Suleimani’s death by an armed drone in Baghdad.

“I just pray to God as he goes through what’s happening, as we speak, that he’s listening to his military commanders for the first time because so far that has not been the case.”

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, opening a rally in Brooklyn Tuesday night, said of the retaliatory attacks, “This is a reminder of why we need to deescalate tension in the Middle East. The American people do not want a war with Iran.”

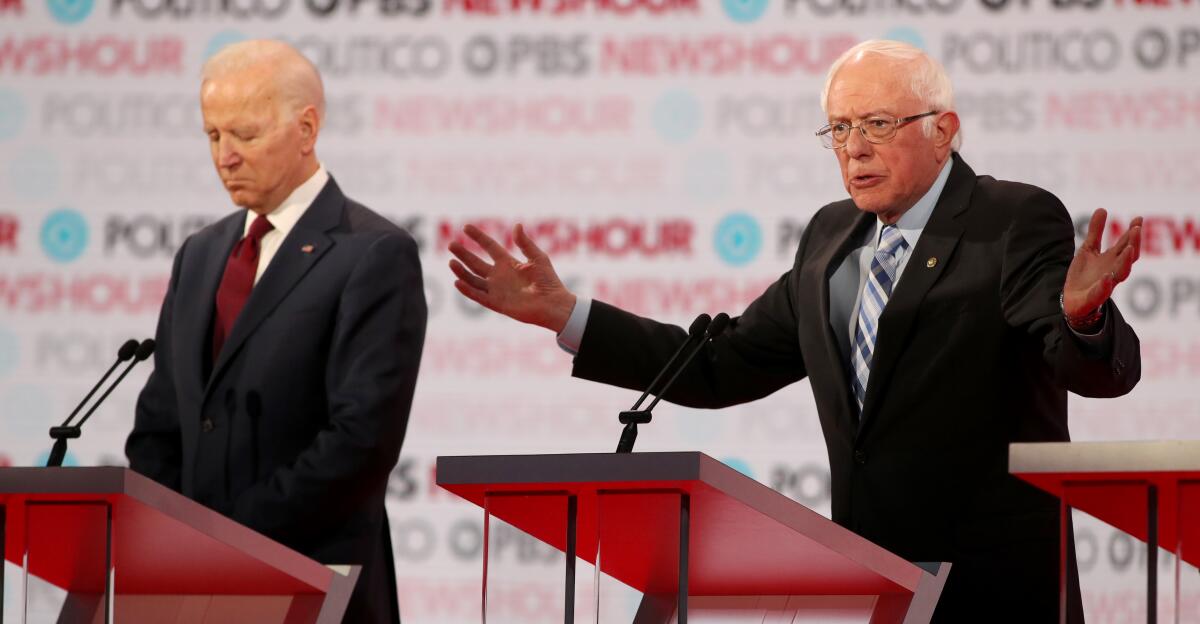

In the days before Iran’s strikes, the rising international tensions had abruptly sharpened Democrats’ disagreements about the U.S. role in the world, personified by the sparring between two front-runners for their party’s nomination — Biden, who’s had a hand in decades of U.S. foreign policy, and Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, an anti-interventionist critic of those policies. Warren has echoed Sanders as she seeks to revive her flagging campaign.

The president’s strike order against Suleimani crystallized what Americans love or hate about Trump: It was the kind of impulsive show of force that fans embrace as tough-guy swagger, but critics fear as his dangerously erratic, even unhinged, behavior. “This brings together a lot of the critiques around Trump,” said Derek Chollet, a former Obama administration Pentagon official who is now executive vice president of the German Marshall Fund. “The weakening of our alliances, the haphazard process, the impulsive decision making, the almost fanatical desire to undo anything Barack Obama did, regardless of whether it is working or not.”

Trump’s decision, which surprised even his own military advisors, came just weeks before Democrats’ nominating contest begins with the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary, highlighting the perceived strengths and weaknesses of the top candidates.

Biden immediately embraced the opportunity to emphasize the value of his foreign policy experience in a world roiled by Trump’s “America first” policies, touching on his years in the Senate, including as chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, and as President Obama’s trusted wing man. He did so in Iowa on Saturday, but Tuesday he gave a more formal speech in New York.

Against a backdrop designed to exude presidential leadership — royal-blue draperies and a row of American flags — Biden promised relief from Trump-era chaos. “I understand better than anyone that the system will not hold unless we find ways to work together,” he said. To Democratic critics who dismiss his faith in his ability to work with Republicans, Biden said, “That’s not a naive or outdated way of thinking. That’s the genius and timelessness of our democratic system.”

Sanders has seized on the crisis to remind voters that he, unlike Biden, voted against the Iraq war and has long warned of the risks of U.S. interventions abroad.

“I have consistently opposed this dangerous path to war with Iran,” Sanders said at a recent Iowa stop. “We need to firmly commit to ending the U.S. military presence in the Middle East, in an orderly manner, not through a tweet.”

That message energizes his antiwar base but may be less appealing to party voters more broadly. A November CNN poll found that 48% of Democratic voters thought Biden was best equipped to handle foreign policy; 14% said Sanders was.

Warren has similarly expressed anti-interventionist sentiment, but Sanders’ supporters initially complained she wasn’t pointed enough in condemning Trump. That underscored the challenges she faces as she tries to appeal to Sanders supporters on the left while also appealing to more moderate voters.

Warren “wants to show contrast and pass the commander-in-chief test at the same time,” said Heather Hurlburt, a former Clinton administration foreign policy official at New America, a think tank.

For Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Ind., and an Afghanistan war veteran, the Middle East tumult is a double-edged sword, spotlighting his status as the only top-tier candidate who has served in the military, but also his political inexperience.

Whether the issue will continue to grab candidates’ and voters’ attention will hinge on the unpredictable fallout in coming days and weeks. Trump’s response to the Iranian attacks will be fraught with political risks, especially to the extent he is seen as having provoked the hostilities. Typically in campaign seasons, most polls find that foreign policy is not a high priority for voters more preoccupied with economic issues, but when American lives are at risk, the stakes rise.

In most national elections since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, issues of war and peace have been powerful factors. In 2002, Republicans benefited from the post-9/11 political environment under President George W. Bush, whose approval rating was over 60%, and the president’s party gained congressional seats in a midterm election for only the second time since 1934.

In 2004, Democrats’ growing opposition to the Iraq war helped propel Sen. John F. Kerry of Massachusetts, a Vietnam War veteran, to the presidential nomination. “I’m reporting for duty,” he said at the convention. But Republicans savagely misrepresented his military record, helping Bush to eke out a reelection victory.

Four years later, opposition to the war also helped vault first-term Sen. Barack Obama first to the party’s nomination over Sen. Hillary Clinton, who voted in 2002 to authorize the war, and then to victory over the Republican nominee, Sen. John McCain of Arizona, a hawkish supporter of the war.

When Clinton ran again in 2016, her early support for the war again was attacked by her primary opponent, this time Sanders. During the general election campaign against her, Trump tapped into Americans’ rising weariness with what he called “endless wars” and promised to bring troops home and to reduce America’s military role in the world.

To date, Democrats’ 2020 campaign had focused mostly on domestic issues — healthcare, income inequality, gun control and climate change — and on Trump’s fitness for office. In the first debates, foreign policy was barely mentioned. Attention grew after Trump’s controversial decision to withdraw from Syria, and his dealings with Ukraine that led to his impeachment.

By their sixth debate in Los Angeles last month, the candidates spent 15 minutes of the two-hour debate on foreign policy topics, more than any other topic, according to a New York Times tally. After the Suleimani killing, foreign policy will surely feature in the next debate Jan. 14 in Iowa, where many voters remain undecided about whom to support in the Feb. 3 caucuses.

Lynn Lovell, 74, an undecided Democrat in Cedar Rapids, said recent developments have made foreign policy more important in his final decision. “I’m just real concerned about what will come after this,” said Lovell, a retiree and Navy veteran who served in Vietnam. “I’m really concerned about the position of commander in chief.”

Sanders has become increasingly personal and pointed in his criticism of Biden’s record, as part of a broader attack that challenges Biden’s claim to be the most electable Democrat. “Joe Biden helped lead the effort for the war in Iraq,” he said Monday, in a tweet that mentioned several issues. “That is not the kind of record that will bring forth the energy we need to defeat Trump.”

Yet Biden clearly sees the surge of voter anxiety over foreign affairs as bolstering his campaign. In his speech in New York, Biden called Trump “dangerously incompetent,” and said he sowed the seeds of turmoil by pulling the United States out of the 2015 nuclear deal with Iraq. “A president who says he wants to end ‘endless war’ in the Middle East is bringing us dangerously close to starting a new one,” he said.

At one of his biggest campaign events to date, a rally Saturday night in Des Moines, Biden spent much of his time recounting his foreign policy achievements. He had a few verbal stumbles, including speaking of former Iraq dictator Saddam Hussein when he meant Osama bin Laden. And he strained to recast some of his past positions — support for authorizing the invasion of Iraq, advising Obama against the mission that killed Bin Laden — as misunderstood triumphs.

As Biden took questions, one voter was skeptical, citing his Iraq vote in the Senate. Biden argued that he merely intended to give Bush a tool to get weapons inspectors into the country, not to invade it, and that he quickly grew disillusioned with the administration’s military campaign.

Times staff writer Seema Mehta contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.