Trump has turned the suburbs into a GOP disaster zone. Does that doom his reelection?

MESA, Ariz. — For decades, there was an unvaried rhythm to life in America’s suburbs: Carpool in the morning, watch sports on weekends, barbecue in the summer, vote Republican in November.

Then came President Trump.

The orderly subdivisions and kid-friendly communities that ring the nation’s cities have become a deathtrap for Republicans, as college-educated and upper-income women flee the party in droves, costing the GOP its House majority and sapping the party’s strength in state capitals and local governments nationwide.

The dramatic shift is also reshaping the 2020 presidential race, elevating Democratic hopes in traditional GOP strongholds like Arizona and Georgia, and forcing Trump to redouble efforts to boost rural turnout to offset defectors who, some fear, may never vote Republican so long as the president is on the ballot.

Even as Republicans worry about Trump’s mercurial presidency and its impact down ballot in 2020, Democrats remain in a high state of anxiety about their own party’s prospects. The result is a rare chapter in American politics when members of both political parties seem wracked with insecurity about their future.

Emily Romney Sanchez is one of them.

The GOP has “gone from defending conservative principles” like free trade and a muscular stance against Russia and North Korea “to defending [Trump’s] latest Tweets,” said Sanchez, a life coach and mother of five in this prosperous desert community. (She is a distant relative of Republican Utah Sen. Mitt Romney.)

Sanchez considers Trump “reprehensible as a human being” and the Republican Party morally bankrupt. “I couldn’t be a part of it anymore,” she said, and as a result, at age 40 the newly registered independent is weighing her first-ever Democratic vote for president.

In an emailed statement, a spokeswoman for the Trump campaign, Sarah Matthews, said “over the next year, our robust ‘Women for Trump’ coalition will continue working to mobilize supporters across the country and share the President’s record of success.”

The erosion of support among suburban women began during the 2016 campaign — for many the breaking point was the “Access Hollywood” video, in which Trump boasted of grabbing women by their genitals — and increased dramatically in the 2018 midterm election, costing Republicans control of the House.

The trend continued in the recent off-year elections, in suburbs from Wichita, Kan., to northern New Jersey to DeSoto County, Miss. Democrats won two of three gubernatorial contests, in Kentucky and Louisiana, in good part because of their strength in those Republican redoubts.

The sentiment extended down ballot as well. Outside Philadelphia, Democrats took control in Delaware County for the first time since the Civil War. In suburban Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C., the party won every state House seat in Fairfax County, a shift nearly on a par with the 2018 Democratic sweep of congressional seats in Orange County.

“It’s amazing the change, in just the last few years,” said Q. Whitfield Ayres, a pollster who has spent decades strategizing for Republican campaigns and causes. “It’s not any one place. It’s everywhere.”

That includes Arizona, where in 2018 Kyrsten Sinema, a congresswoman from the Phoenix suburbs, became the first Democrat in 30 years to win a U.S. Senate seat. She ran as a centrist focused on bipartisan problem-solving, a direct appeal to pragmatic suburban voters, and her success is seen as a model for turning the state from red to blue in 2020 — or at least making Arizona competitive in a way it has not been in decades.

With 11 electoral votes, Arizona is a bigger prize than Wisconsin — a Midwestern battleground both parties view as a key to the election — and the Grand Canyon State is expected to draw lavish attention and a fortune’s worth of advertising over the next year. Visiting last month, Vice President Mike Pence said he and Trump “are going to be in and out of Arizona a lot.”

The ancestral home of conservative icon Barry Goldwater and John McCain, the 2008 Republican nominee, Arizona has undergone a slow but steady transformation as the growing Latino population and a flood of newcomers from places like California erode Republicans’ long-standing hegemony.

The movement has been accelerated by Trump and his alienation of voters in typically Republican suburbs like Scottsdale, Gilbert and here in Mesa, which has grown from a far-flung satellite of Phoenix into the state’s third-largest city.

Of course, the president has plenty of supporters amid the sere landscape and red-tiled rooftops of the region’s sprawl-to-the-horizon suburbs, including some like Sarah Roork who came around after initial skepticism.

She has more work, Roork said, thanks to the percolating economy, and brings home more pay as a result of the tax bill Trump signed into law. “Actually, I’m pleasantly surprised on policy,” said the 43-year-old flight attendant.

Sandy Wong said the reasons she reveres the president are almost too many to list.

“Sure he has a so-called unpredictable, so-called un-presidential manner of speaking,” said the 65-year-old retired healthcare executive, who does part-time Web design from her home in Ahwatukee, a family-oriented enclave of Phoenix in the foothills of South Mountain.

“But his very explosive rhetoric is very effective to stop this toxic metastasizing political power that Democrats, even more left of [President] Obama, represent at this time,” Wong said.

That, however, is a distinctly minority view; surveys have consistently shown most suburban women have little regard for Trump.

The exodus stems not so much from his policies — many of which are standard GOP fare, like cutting taxes and regulations — but rather the president’s behavior: the bullying, belligerence and ad hominem insults.

“Sometimes I want to print out every single one of his Tweets and tape them to people’s doors,” said Christie Black, a 35-year-old stay-at-home mom who abandoned the GOP and voted independent in 2016 rather than support Trump. “I want them to see in writing that these are the things he’s saying. Those are worth tax cuts to you?”

“Yeah,” her brunch companion, Kaija Flake Thompson, chimed in sarcastically. “We have no moral compass, but, hey, we have conservative judges!”

(Thompson’s brother, former Arizona Sen. Jeff Flake, is a prominent Trump critic. But Thompson, a 41-year-old nurse, said her feelings about the president have nothing to do with his attacks on her kin; others in the family strongly support Trump, making for some lively discussion.)

Neither lapsed Republican has decided on a 2020 candidate, though both like Pete Buttigieg, the youthful mayor of South Bend, Ind. Black, a self-described conservative, said she could even vote in good conscience for Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, with her vision of a vastly expanded federal government.

“We would still have our checks and balances,” Black said, which she fears are steadily eroding under Trump. “I think right now the most important thing is to get those principles of democracy tied down, get that return to regular order, and then we can worry and get back to squabbling about conservative versus liberal.”

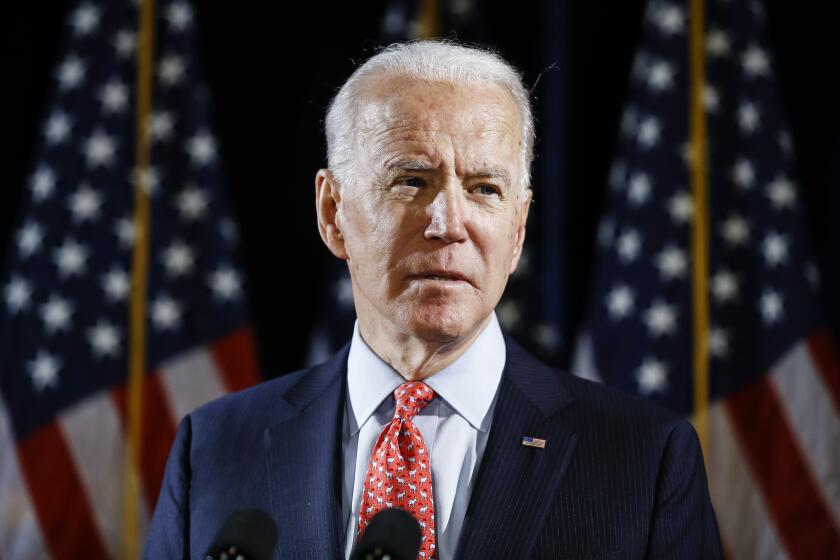

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

Trump is not ceding the suburbs. While relying heavily on massive rural support to win reelection, the president and his political team hope to win back many disaffected women by leaning into the strong economy and promoting issues like paid family leave, school choice, female entrepreneurship and aggressive efforts to secure the border with Mexico.

Perhaps most crucially, Trump and GOP strategists are counting on Democrats fielding a nominee whom women voters, whatever their feelings toward the president, will find even more off-putting.

“If the Democratic nominee wants to get rid of ICE” — Immigration and Customs Enforcement — “decriminalize the border, give free healthcare and eliminate the private option, and believes there’s more than two genders ... they’re not going to win here,” said Chuck Coughlin, a veteran Republican consultant in Phoenix, who is unaffiliated with Trump’s campaign.

Courtney Davis, for one, remains open to persuasion.

With a real estate business and four children ages 5 to 16, she has little time for politics and hasn’t paid much attention to the 2020 campaign. She voted for Trump in 2016, Davis said, “as the lesser of two evils” because she couldn’t abide Democrat Hillary Clinton.

While Davis, 39, doesn’t care much for Trump’s behavior — “I don’t love his tactics. I don’t love his approach” — she remains a registered Republican and can see voting for him again.

It all depends, Davis said, on whom Democrats present as the alternative.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.