Deval Patrick enters Democratic presidential race

WASHINGTON — Former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick launched a late-entry bid for the Democratic presidential nomination on Thursday morning, joining an already crowded field with a campaign that will aim to position him as a pragmatist well-positioned to take on President Trump.

“I admire and respect the candidates in the Democratic field. But if the character of the candidates is an issue in every election, this time is about the character of the country,” he said in a video launching his candidacy.

In an interview with his hometown newspaper, Patrick did not minimize the long odds against his candidacy.

“I recognize running for president is a Hail Mary under any circumstances. This is a Hail Mary from two stadiums over,” he told the Boston Globe.

The newly minted candidate officially filed for New Hampshire’s primary on Thursday. He plans to fly to California for appearances on Saturday and Nevada on Sunday, according to a person familiar with his plans. The California Democratic Party is holding a convention in Long Beach this weekend, and Nevada Democrats have a candidate forum scheduled for Sunday.

In an interview with “CBS This Morning,” Patrick offered thinly veiled criticisms of two of the current leading candidates, former Vice President Joe Biden and Patrick’s fellow Massachusetts politician, Sen. Elizabeth Warren.

“We seem to be migrating to, on the one camp, sort of nostalgia — let’s just get rid, if you will, of the incumbent president and we can go back to doing what we used to do,” he said. “Or, it’s our way, our big idea, or no way.”

“Neither of those, it seems to me, seizes the moment,” he said.

In case anyone thought the implied criticism was accidental, Patrick repeated the same comment after filing in New Hampshire.

Asked on CBS about a couple of major issues in the campaign, Patrick said he opposes “Medicare for all” but supports a “public option” that would allow people to enroll in a government-sponsored health plan rather than private insurance. And he said he supports higher taxes on the richest Americans, but not necessarily the wealth tax that Warren has backed.

“I don’t think wealth is the problem, I think greed is the problem,” he said.

Patrick is the only African American to be elected Massachusetts governor. A gifted orator, he impressed voters during his two terms with a personal story that took him from an impoverished childhood in Chicago to the prestigious Milton Academy outside of Boston on scholarship and then Harvard University and Harvard Law School. In addition to serving as governor, he headed the civil rights division of the Justice Department during the Clinton administration.

He has close ties to President Obama and his allies.

But, as he acknowledged, Patrick faces tough odds in the presidential race. His resume is laden with the type of corporate jobs that are out of style with today’s Democratic electorate. Since 2015, he has been on the payroll of Bain Capital, the private equity firm Democrats pilloried when its founder, Mitt Romney, who served as Massachusetts governor before Patrick, ran as the GOP nominee for president in 2012. He stepped down from Bain earlier this week in preparation for running, an aide confirmed.

And he is entering the race at a time when other candidates have already been in the field for many months, building their organizations and spending time with voters. Several prominent hopefuls have already dropped out, and voters have given no indication they are looking for alternatives to the candidates already running: Most polls that have asked show a large majority of Democratic voters satisfied with their existing choices.

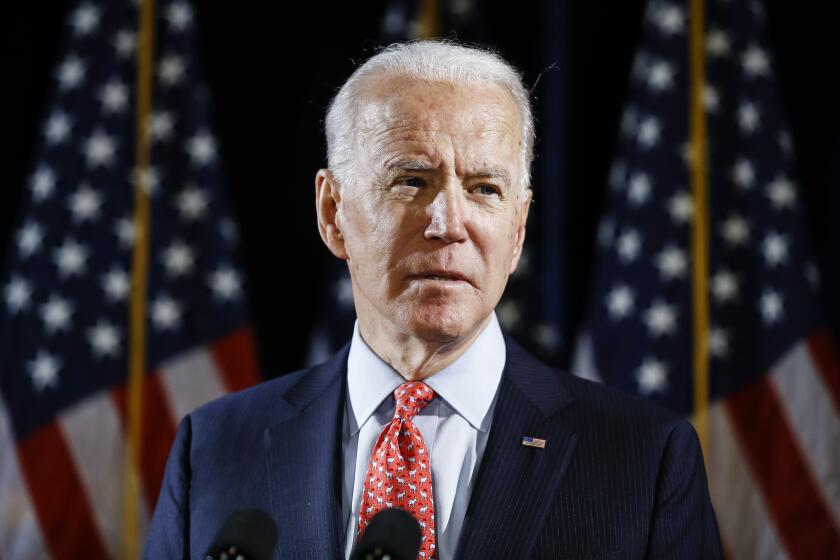

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

Patrick will also be hard pressed to find experienced staff to run his operation. Experienced operatives who worked with him in the past joined other candidates when Patrick announced earlier this year that he would not be joining the race.

He had prepared carefully for a possible candidacy, but bowed out in December, citing the “cruelty of our elections process.” Patrick has two grown daughters and a wife — attorney Diane Patrick — who has publicly discussed the effects of the political process on her depression.

Although Patrick appeared to have won his family’s blessing this time, his late announcement this week caught even some of his closest political confidants off guard. But Patrick has long been nostalgic about his underdog status when he entered the 2006 gubernatorial primary in Massachusetts as a relative unknown, facing off against the state’s sitting attorney general.

His decision to enter the race now comes as some establishment Democrats worry that Biden, the leading moderate in the race, is losing ground to more progressive rivals. Biden’s sometimes unsteady performance on the stump has left some voters questioning whether the 78-year-old is up to taking on Trump.

Patrick, 63, will likely try to position himself as a more viable alternative to Biden than Pete Buttigieg, a 37-year-old whose political experience is limited to serving as mayor of the city of South Bend, Ind., which is roughly the size of Burbank, but who has risen in polls to become a leading candidate.

Patrick’s record as a trailblazer for African Americans could position him to connect with black voters, a mainstay of Biden’s support, but a group with whom Buttigieg has done poorly so far.

Yet Patrick will find himself up against two other prominent black candidates who have also made racial justice a central focus of their campaigns, California Sen. Kamala Harris and New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker.

And his launch comes as another centrist with deep political experience — and far deeper pockets — is flirting with making his own late entry into the race. Should billionaire and former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg jump in, he would immediately be in Patrick’s lane, and have a lot more resources for his campaign.

Patrick has long been friends and political allies with Obama, sharing political advisors, speaking styles and vacation time on Martha’s Vineyard. He gave a rousing speech at the 2012 Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, N.C., bringing delegates to their feet as he told Democrats “to grow a backbone and stand up for what we believe.”

Patrick was also an important ally for Warren, delivering a key endorsement in her initial race for U.S. Senate when she was under attack for her thin claims of Native American ancestry. The endorsement came during the 2012 Democratic primary and was coupled with a spirited speech at the state Democratic convention that helped turn the race for Warren against the Republican incumbent, Sen. Scott Brown.

But Patrick has always been uncomfortable with the anti-corporate rhetoric of Warren and other progressive Democrats. He served as an attorney for both Texaco and Coca-Cola before he made the move to politics, and he did not join fellow Democrats in attacking Bain during the 2012 presidential campaign.

He said Thursday that he had spoken with Warren before making his announcement. It was “kind of a hard conversation for both of us,” he told reporters in New Hampshire.

Patrick’s service on the board of the parent company of Ameriquest, a subprime lender, was a liability when he initially ran for governor in 2006 and would likely come up again if his candidacy for president gains traction. After leaving office in 2015, he took the job with Bain, surprising many top Democrats who worried the position would kill any aspirations for higher office.

A transformational figure in his state’s politics — Patrick was the only African American governor in American history to win two terms — he will seek to leverage his popularity in neighboring New Hampshire, a crucial state in the primary contest because of its early position on the calendar.

But he will face steep competition there. Warren and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders already have deep networks and strong voter support in New Hampshire, where they, too, are well known to locals.

In Massachusetts, Patrick came from outside his state’s insular political machine and clashed with old-line Democrats in the state Legislature when he first sat in the governor’s traditional corner office in the statehouse. But by the time he left office, he had formed a working relationship with many of the state’s power brokers.

As governor from 2007-15, he reorganized the transportation system that was scarred by billions of dollars in debt incurred from the so-called “Big Dig” project that buried the interstate overpass that went through the center of Boston. He raised the state sales tax and implemented the healthcare law that had been enacted under Romney, which vastly expanded access to insurance and became the model for the federal Affordable Care Act.

He promoted the state’s large biotech industry and signed legislation allowing casino gambling. Along the way, controversies plagued the Patrick administration. There were lapses in the child welfare system, and the courts overturned thousands of convictions during his tenure after a rogue chemist in the state crime lab admitted to falsifying evidence.

He hopes that political record will now help propel him forward in a long-shot race that will test his moderate message.

Although acknowledging the long odds, he said in the CBS interview that he had decided the gamble was worth taking, saying: “You can’t know if you can break through if you don’t get out there and try.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.