Trump announces partial deal with China, but comprehensive solution still looks far off

WASHINGTON — Facing a slowing U.S. economy, growing complaints from farmers and political pressure over impeachment, President Trump on Friday announced a partial, tentative trade agreement with China despite his long-standing insistence that he would only strike a tough, comprehensive deal with Beijing.

Trump said the agreement, which came after a resumption of high-level trade talks in Washington this week, would include a “tremendous” increase in Chinese purchases of U.S. farm goods. He said that Beijing also would address American concerns about intellectual property, technology transfer, financial services and currency, although there was little specificity disclosed on most of these issues and Trump noted that this “Phase 1 deal” was an agreement in principle “subject to being papered” in the next few weeks.

In exchange, Trump agreed to put off a relatively small step-up in tariffs on $250 billion of imports from China that was to take effect Tuesday. He left on the table the threat of new 15% tariffs on tens of billions of dollars of China-made cell phones, laptops and toys on Dec. 15, though Trump’s chief trade official, Robert Lighthizer, suggested that those duties also would be suspended if the agreement is finalized.

All in all, the tentative deal marked progress after a breakdown in talks in May led to further escalation of tariffs, heightened tensions in bilateral relations, consternation in financial markets and pain for domestic manufacturers. “Finally, a ray of hope for the U.S.-China trade relationship,” said Myron Brilliant, head of international affairs at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Yet in many ways, the agreement did little more than bring negotiations back on track to where the two sides were before spring. Significantly, there was no indication that Beijing was prepared to give ground on key structural issues, including industrial policies supporting Chinese tech companies, matters of cyber-security and market access for sensitive areas like cloud computing.

“The deal seems to feature mostly issues that are politically safe for both sides,” said Michael Hirson, head of the Eurasia Group’s China practice. “The really tough issues that are needed to reach a broad deal are getting kicked down the road.”

Moreover, he said, “I think of this as being a truce, but we shouldn’t be overly confident that this deal can be sustained, and there are real limits in the ability to improve broader U.S.-China relations.”

For Trump, it was far from a major breakthrough or the kind of sweeping deal that he has promised in order to re-balance trade and address long-standing American concerns about China’s unfair economic practices.

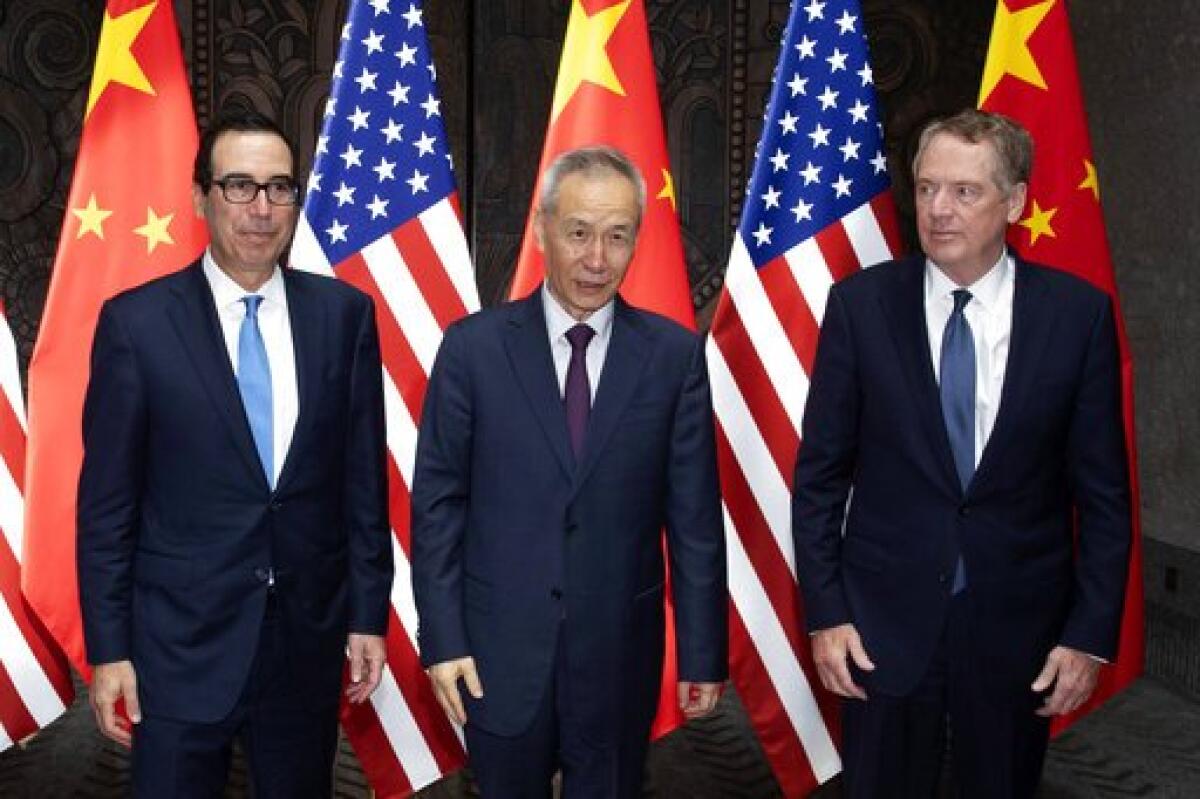

In remarks in the Oval Office, where he met with China’s top trade envoy, Vice Premier Liu He, Trump repeatedly highlighted the Chinese farm purchases, indicative of his desire to shore up support from farmers in key states where the trade war has hammered a core constituency as Beijing targeted retaliatory tariffs on soybeans and other farm goods.

Trump said China had agreed to boost U.S. agricultural purchases to $40 billion to $50 billion, from an annual high of $16 billion. He said half-jokingly that American farmers are going to have to “immediately buy more land and get bigger tractors.”

But it wasn’t clear over what time period the Chinese would make those imports or even whether China had the capacity to boost purchases by that much. There was nothing in writing issued Friday, and Liu, who spoke briefly after meeting with Trump, provided no specifics about farm purchases or any part of the agreement, saying only that “we have made substantial progress in many fields.”

U.S. businesses and stock markets, which went up sharply Friday, are hoping that the agreement could open the way for a bigger deal, but it also could turn out to be another short-lived truce in Trump’s unpredictable trade war with China, which has seen a gradual escalation of tariffs.

David Loevinger, a former senior Treasury Department official on China affairs, said that even a “super-skinny deal” was better than a deepening trade war. But given the off-and-on nature of Trump’s trade war with China and a widening of tensions with Beijing, especially over technology competition, he asked: “Will this turn into an actual agreement? And how long will it stick?”

He noted that China’s pledge to buy more U.S. soybeans and other agricultural goods is something they offered to do earlier this year.

“Agreeing to import more ag products is no big concession for the Chinese,” said Loevinger, who’s now an analyst for TCW Emerging Markets Group in Los Angeles. “They have to eat, and they’re running out of pigs,” he added, referring to a staple of the Chinese diet lately threatened by an outbreak of disease.

Derek Scissors, a China expert at the American Enterprise Institute, said that at one point during the past couple of years of sporadic negotiations, Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin had talked about $1.2 trillion in Chinese purchases.

“Today the president was bragging about $40-$50 billion,” Scissors said, adding that Trump could come under fire from critics, particularly his political opponents. “The Democrats can start by saying the Trump administration took years just to end up downsizing a key part of the deal by a trillion dollars,” he said.

Trump did not roll back any of the existing tariffs he has imposed on some $360 billion of Chinese goods, a politically popular move with China hawks, and his supporters who have applauded his get-tough strategy.

Scissors noted, however, that as much as Trump likes tariffs, the president has good reason to back away from imposing more taxes on Chinese goods, especially ordinary consumer products.

Trump’s planned Dec. 15 tariffs are significant in that they will add 15% taxes on some $160 billion of mostly consumer goods, including cell phones and computers — something that businesses warn will pinch American households and risk a further slowing of economic growth, which would almost certainly hurt Trump’s reelection bid.

“Nobody right now wants those tariffs,” said Scissors, who regularly talks with administration officials.

With or without tariffs, a comprehensive trade deal appears to be a long way off. And it may not be possible at all, given that the U.S. confrontation with China has escalated far beyond trade.

“Whatever kind of deal it is, it’s not a solution, not an answer,” said Clyde Prestowitz, president of the Economic Strategy Institute and a former trade negotiator in the Reagan administration. “It will become increasingly difficult for China and the U.S. to live together in the way we have been living together,” he said, noting that the fundamental problem is trust and the difference in values.

Ahead of the talks this week, the Trump administration cited human rights violations in restricting visas for some Chinese officials, and it put more Chinese entities — in addition to the telecom giant Huawei — on a U.S. blacklist that would prevent prominent tech firms from buying crucial American components.

The administration also is reportedly considering a range of other measures to clamp down on China, including restricting Chinese access to U.S. capital markets and blocking American pension funds and universities from Chinese investments. Technology is a key battleground.

“The Chinese are coming more and more to the view that tariffs are really a second-order consideration in the overall economic relationship,” said Nicholas Lardy, a China economy expert at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “I think the evidence is very clear that those people in the Trump administration that want a technology decoupling have gained the upper hand and they’re moving on every front possible to reduce the flow of U.S. technology to China.”

Trump previously has said that Huawei could be a part of the trade negotiations, and news reports in recent days have indicated that Trump was prepared to approve some licenses that would allow for nonsensitive U.S. components to be exported to Huawei. Lighthizer said Huawei wasn’t discussed during the talks.

Huawei recently rolled out its new Mate 30 mobile phones in Europe, but with the U.S. export prohibition, Google’s Android apps, including Google Play, Maps and YouTube, are not installed and won’t work on the phones.

“If you’re going after a premium handset market in Europe, but you don’t come with those apps, who’s going to spend money on a Huawei phone?” said Samm Sacks, an expert on cybersecurity policy and China’s digital economy at New America, a nonpartisan think tank.

Beijing and Chinese companies have been racing to become less dependent on foreign and particularly American firms and develop their own tech capabilities. But in some cases, that could take years.

In the meantime, Chinese firms had been stocking up on U.S. chips and other components. Even so, Sacks said that there are limits to that. Even Huawei executives have told her, she said, “You can stockpile gear, but you can’t stockpile apps.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.