Pelosi hopes prescription drug bill will give Democrats something to show voters in 2020

WASHINGTON — Democrats in 2018 seized control of the House of Representatives in large part because they convinced voters that they would be the party to protect Americans’ healthcare.

But now, as the 2020 presidential campaign narrows the window for passing significant legislation and dominates headlines, rank-and-file Democratic House members have little to show on healthcare, an issue that is still top of mind for voters.

Though the Democratic-controlled House put an end to Republican efforts to repeal or chip away at the Affordable Care Act, Democrats so far have failed to get any of their other healthcare promises signed into law, such as lowering costs and expanding access.

“Every chance I get to talk to leadership, I am stressing the No. 1 concern I hear back home is the cost of prescription drugs,” said Rep. Anthony Brindisi (D-N.Y.), who won a seat in 2018 that had been held by a Republican. Healthcare as a political issue “hasn’t died with the end of the 2018 election. It’s still alive and well, and will be front and center in 2020. So let’s get it done.”

Brindisi is one of several House Democrats, mostly freshmen, who are clamoring for the Democratic-led House to hold votes on legislation regarding prescription drugs, surprise medical bills and other issues.

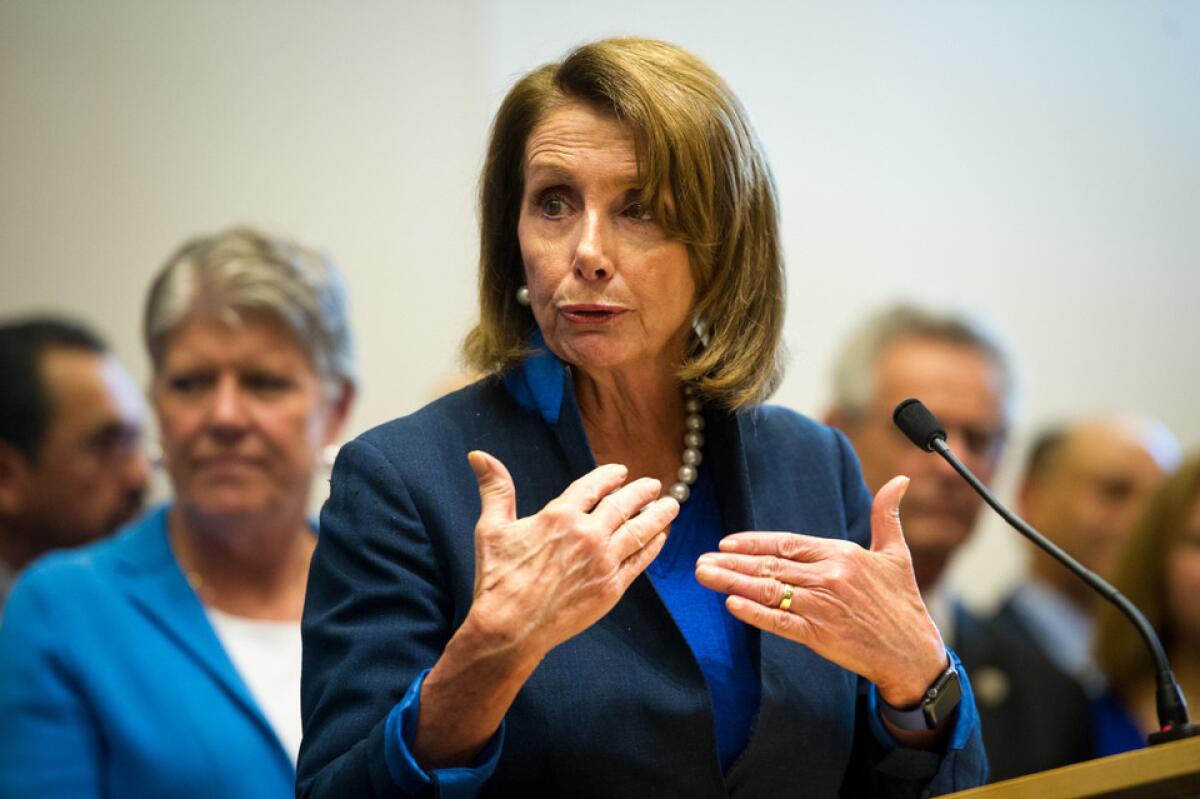

Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) released a prescription drug plan Thursday. lt is unlikely to get a vote on the House floor until later this year.

The plan requires drugmakers to negotiate prices with the government for a certain number of drugs with little competition, both in Medicare and on the private market. Pharmaceutical companies that refuse would face steep fines. The maximum price would be comparable to costs in other countries, similar to a provision the Trump administration has touted. It would also cap how much drugmakers can raise their prices in the Medicare program.

House and Senate Republicans immediately trashed the plan, particularly the government negotiation, as just another part of Democrats’ “socialist” agenda.

Progressives, meanwhile, expressed worry that the bill was not ambitious enough. Rep. Mark Pocan (D-Wis.), co-chairman of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, criticized the fact that the government would negotiate prices of only 25 drugs per year. The bill’s backers framed the 25 number as a floor, however, arguing that the maximum number is 250. “We think it could be much more robust,” Pocan said.

Moderate Democrats were more excited about the direction of the bill. Both moderates and progressives indicated they’re eager to address the issue.

“When we have caucus meetings, every single meeting, I’m like, ‘What is the plan on pharmaceuticals, on infrastructure?’” said Rep. Elissa Slotkin (D-Mich.), who, like Brindisi, will be running for reelection in 2020 in a Republican-leaning district. “Those of us who flipped districts [from Republican to Democrat] and are very close to the ground on these issues know that what people are expecting of us comes in the form of affirmative legislation.”

A key question will be how the White House responds to the House bill. Unlike high-profile House legislation proposed this year on background checks for guns, climate change, LGBTQ rights, election reform and other issues, President Trump has repeatedly signaled a willingness to engage with Democrats on prescription drug policy.

Rebuffing Republican orthodoxy on the issue, he has said he would hold pharmaceutical companies accountable and reduce out-of-pocket drug costs. He has repeatedly said he would support requiring drugmakers to negotiate their prices with the government. If he supports a Democratic plan, he is likely to bring many GOP lawmakers along with him — enough to overcome the powerful prescription drug lobby’s opposition.

On Thursday, Trump tweeted that it was “great to see Speaker Pelosi’s bill today. Let’s get it done in a bipartisan way!”

And earlier this week, Trump said he’d be willing to work on a prescription drug plan with House Oversight Committee Chairman Elijah E. Cummings (D-Md.), one of several Democrats investigating the White House. As recently as July, Trump attacked Cummings as a “brutal bully” who was failing his “rodent-infested” Baltimore district, but now the president says he looks forward to working with him. “We’re going to do much lower drug prices over the next year,” Trump said, “if we can get the help from Congress.”

That remains to be seen. Other than bills to keep the government funded, there have been no major bipartisan bills signed into law this year, and Senate Republicans are unlikely to take up any of the top-priority bills passed by House Democrats.

Prescription drugs could be one of the only exceptions, giving Democrats an opportunity to notch a legislative victory on a bill that they can argue will benefit consumers. A bipartisan agreement could also serve as fodder for the campaign trail to prove that Democrats can work with Republicans and get things done in a divided government. That will be particularly important for the many freshmen Democrats in Republican-leaning House districts with Trump on the ballot.

“These members need to show they’ve made a difference up here. It’s not just passing something out of the House,” said Rep. Kurt Schrader (D-Ore.). “You want a win? You’ve got to show you actually made a difference.”

On the flip side, some Democrats are skeptical of giving Trump a legislative victory that he too can tout on the trail. That concern is more acute in the Senate, where Democrats are trying to unseat several Republican incumbents in next year’s races.

Pelosi told a group of moderate Democrats in a closed-door meeting this week that she wants victories on both prescription drugs and the White House’s replacement for the North American Free Trade Agreement. “I don’t care if it gives the president a win,” she said, according to a Democratic lawmaker in the room.

One possible outcome is that prescription drug provisions are added to a must-pass bill to keep the government funded. Several recent changes to prescription drug policy — albeit less ambitious than what’s on the table now — have been tucked into larger bills in order to limit their exposure to political opposition.

The House is scheduled to be in session for only eight more weeks this year, adding a sense of urgency to the issue.

“The biggest concern is probably the timeline,” said Rep. Ami Bera (D-Elk Grove), citing the calendar and the fact that significant legislation rarely moves in a presidential election year. “Right now you can probably keep presidential politics out of it. ”

In recent weeks, the White House has stepped up its outreach to congressional Democrats on the issue. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar met with a group of members for lunch last week to discuss what the administration has done to address rising drug costs. He emphasized the president’s interest in the issue, saying Trump asks him about a prescription drug plan every time they see each other.

The meeting was cordial, according to lawmakers, but Democrats say they are skeptical of the man who led the agency that has, in their view, undermined the implementation of the Affordable Care Act for political reasons. They also believe they can’t be confident in what Trump thinks about anything unless they hear it directly from the president.

“I thought [Azar] was very smooth in what he said. It wasn’t clear to me that he was speaking for the president,” said Rep. Donna Shalala (D-Fla.), a former Health and Human Services secretary. “He doesn’t necessarily have the political clout. Health policy seems to be run out of the White House.”

A prescription drug plan faces steeper odds in the Republican-controlled Senate. The Senate Finance Committee, led by the bipartisan pair of Chairman Charles E. Grassley (R-Iowa) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), has approved a bill that would cap how much drug prices can go up in Medicare. The plan has the support of the White House, but several Republicans opposed it in committee and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) is loath to bring up any legislation that divides Republican lawmakers.

Grassley has positioned his plan as moderate, warning Republicans and drugmakers this summer that Pelosi and Trump could cut a deal directly on a more liberal plan. If they did so, “look at what that would do to everything that we Republicans stand for in the United States Senate.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.