As the next debate nears, trailing candidates soldier on in obscurity

MANCHESTER, N.H. — Bill de Blasio bounded into New Hampshire with a turnaround plan for his floundering presidential campaign: opposition to robots.

The New York mayor predicted that a newfound focus on protecting American workers against automation through imposition of a “robot tax” could lead to his electoral salvation.

For the record:

10:55 a.m. Sept. 11, 2019An earlier version of this article reported that former Colorado Sen. Gary Hart surged from relative obscurity to become a top-tier candidate during the presidential campaign of 1988. Hart rose to national prominence in 1984.

“People are responding to it,” he said to a smattering of reporters over the weekend, noting that the issue even allowed him to find common ground with an archenemy, Tucker Carlson of Fox News. “That is the kind of thing that causes a lot of people to pay attention.”

So it goes for the dozen or more presidential candidates whose place on the campaign trail straddles obscurity and oblivion. With donor money drying up, poll numbers going nowhere and the media losing interest, candidates struggling with single-digit (or even zero-digit) voter support are reassessing, rejiggering and relaunching.

A senator, one governor, one ex-governor and two congressmen have already quit the race. Many of those who haven’t are facing regular indignities on the trail, traveling repeatedly to states with early primaries only to find voters who wouldn’t recognize them standing in line at Dunkin’ Donuts.

Half of the remaining field of 20 fell short of the Democratic National Committee’s threshold to be on the debate stage Thursday, a potential death blow to their chances. Even several who do have spots on stage seem stalled in a contest dominated by the top few.

Yet the also-rans soldier on — even when staying in the race threatens to damage their future political prospects — fueled by a great engine of political campaigns: irrational hope.

“Virtually every presidential nomination turns up a surprise candidate,” said former Colorado Sen. Gary Hart, who became that candidate in 1984. He was at the New Hampshire Democratic Convention last weekend to give a boost to a fellow Coloradan, Sen. Michael Bennet.

Bennet takes comfort in the fact that Hart was nowhere at this point in his run. Because Bennet is nowhere. Not even at 1% in the average national poll, and no better in the surveys of early-voting states.

“The voters in Iowa and New Hampshire are just beginning to look,” Bennet argued after Hart stepped away from the microphone. He didn’t let Hart step away for long.

“Come back, Sen. Hart. Come back,” Bennet said, savoring the rare burst of national media attention Hart drew to the campaign.

Bennet mapped out a path to victory: Voters will ultimately recognize him as distinct, he said, because he offers practical solutions and an ideological bridge building rather than the kind of polarizing politics that could deliver President Trump another term.

That’s a common refrain from the large number of also-ran candidates who are centrists, all of whom are watching Joe Biden’s uneven performance on the stump and waiting for lightning to strike the front-runner.

“I call them the understudies,” said Mike Murphy, a Republican strategist who helped the late Sen. John McCain orchestrate a comeback. “They are all waiting for Biden to crumple.”

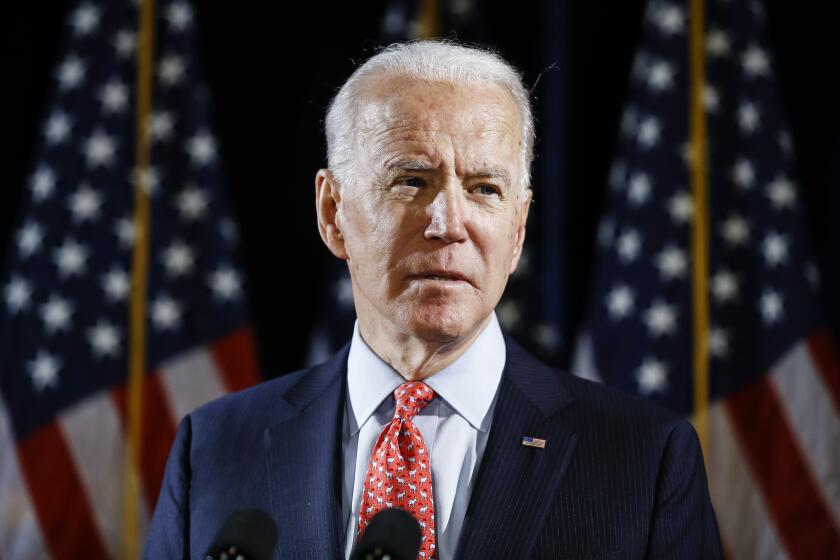

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

Among those he includes in that category is Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota. When she launched her campaign in a snowstorm in February, donors filled her coffers with $1 million in 24 hours. It’s been slow going since. In some national polls, she’s in Michael Bennet territory.

After giving a talk to a few dozen voters in New Hampshire on Friday, Klobuchar joked in an interview about recapturing the energy of the launch.

“It’s going to snow again,” she said. “Then we can really bring out those photos.”

The Klobuchar campaign plans to build on the platform of the debates (she qualified for this week’s event) and the one place the candidate is getting a little traction — Iowa, next door to her home state.

Her team is bulking up organizing and seizing on the advantage of the senator being from the region to spur grass-roots momentum. That sort of strategy, heavy on building an organization in one or two early contests, worked for candidates like Hart and McCain, and also Jimmy Carter and John F. Kerry. All were written off by the national media as also-rans but came roaring out of early-state victories that they built by wearing down their shoe leather in Iowa or New Hampshire.

“Nobody in my lifetime who has led in the polls this far out has gone on to be president in our party,” said Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey, another in the army of the stalled, as he talked with a small gaggle of reporters after an event in Goffstown, N.H. “In fact, if you are leading in the polls right now, you should worry.”

Some who have been through the pain of a floundering run say hanging in there makes perfect sense.

Michael Meehan, who was an advisor to the 2004 Kerry campaign, recalls the talking heads on the Sunday shows didn’t even bother to mention his candidate in their predictions for Iowa a week before the caucus.

Kerry won Iowa. And eventually, the nomination.

“Even if you finish second in Iowa but had no money in the bank, with today’s fundraising tools, you could make 20 million bucks in one day,” Meehan said. “That is enough to put gas in the plane to get you to New Hampshire. It is lightning in the bottle, but it is totally doable.”

Of course, only one candidate, at most, can be the surprise of the year. And Murphy takes a dimmer view of this year’s crop.

He recalled a 2 a.m. meeting with a flailing McCain late in 2007. The bar had already closed for the night, leaving the two of them to drag chairs over from another room. McCain was considering dropping out. Murphy, who was backing another candidate, said he advised the senator to hang in there. McCain was getting no traction in Iowa, but his popularity in New Hampshire, where he had been all the rage in 2000, could still be his ace, Murphy said.

“I told him, ‘Why on Earth would you drop out when you haven’t played that card?’”

McCain focused exclusively on the Granite State, and his win there propelled him to the 2008 nomination.

But Murphy questions whether some candidates in the current race have any card to play. Stubbornness, he warns, can come at a cost.

“If you start to look like a loser on the national stage, it takes a toll back home,” Murphy said. Former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke’s remarkable plunge in popularity on the national stage, for example, could threaten his future viability as a statewide candidate.

Klobuchar’s long-held reputation as a workmanlike problem solver has been battered by presidential politics. Thanks to national media scrutiny, voters now associate her with allegations of serial mistreatment of underlings.

Others, though, have little to lose. South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg rocketed from unknown to national celebrity with a campaign promising youth, diversity, pragmatism and intellectual appeal. He is vacuuming in enough campaign cash to launch television ads and open new offices throughout early voting states. He easily qualified for this week’s debate.

Buttigieg may never break into the top tier. But he has clearly raised his national profile, which is important for a Democrat stuck in an increasingly Republican state.

Hawaii Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, who fell short of earning a spot at this week’s debate, but might yet qualify for October, is building another kind of momentum. The campaign has enabled the combat veteran to build a swelling movement of anti-interventionist, anti-establishment activists.

“People who have supported Bernie Sanders in the past are coming to my campaign now,” Gabbard said in an interview, just before Harvard professor and progressive activist Lawrence Lessig hosted her at a well-attended “Democracy Town Hall” in Dover, N.H.

“So long as this foreign policy establishment retains its power and the status quo is continued, we will never have the resources we need to serve those urgent needs of people here at home,” she added.

De Blasio is aiming to spark his own movement with robots. One glaring roadblock: Another candidate got there first. Entrepreneur Andrew Yang has been talking about robots from Day One, and he’s been successful, building a campaign that is more popular and durable than those of several veteran politicians.

The odds of De Blasio taking the reins as the robot-apocalypse candidate are long. Yang qualified to be on the stage Thursday night.

De Blasio didn’t come close.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.