Small donors don’t cut it for many Democratic candidates. Back to the rich

WASHINGTON — After all the promises that fundraising-as-usual was behind them and that charming the wealthy over canapes would take a backseat to chatting with regular human beings, Democratic presidential candidates spent a lot of time this summer in the Hamptons.

Martha’s Vineyard, Brentwood, and the well-manicured estates of Silicon Valley, too.

For the record:

1:42 p.m. Sept. 5, 2019A Sept. 4 article that mentioned Joe Biden’s attendance at a fundraiser hosted by Nelson Cunningham referred to Cunningham’s “lobbying firm.” Some members of the firm are lobbyists; Cunningham is not a registered lobbyist.

Paying the bills without paying regular visits to the seaside homes and penthouse apartments of rainmakers turns out to be a lot harder than many candidates hoped.

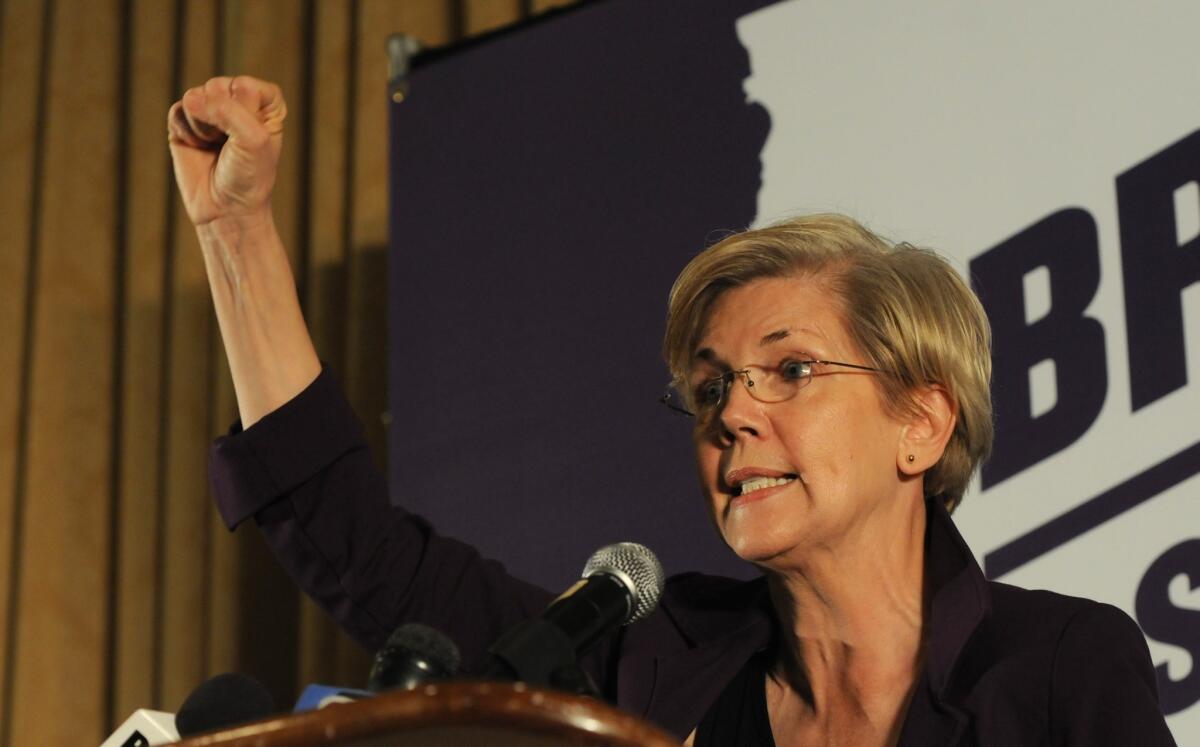

Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont has twice funded robust presidential campaigns almost exclusively with small online contributions. Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts has largely succeeded, as well. The others, not so much.

“A lot of them had a big burst of online fundraising at the beginning and thought they were going to be able to keep it going,” said Joe Trippi, who managed the 2004 presidential campaign of Howard Dean, an early phenom at grass-roots fundraising. “They hired beyond their ability to sustain it. Several had to pull back.”

Trippi said he saw a similar pattern with Dean. Small donors can be less forgiving and reliable than big-dollar contributors who grow invested in a candidate’s success. With small donors, success can breed success, but a falter on the trail can touch off a cash crisis.

A number of candidates whose launch gave the appearance of Sanders-like momentum with small donors have seen their online cash machines sputter. Some have nearly flatlined.

Former U.S. Rep. Beto O’Rourke, for example, built his name motivating grass-roots donors when he unsuccessfully ran last year for the Senate in Texas. He rocketed into the presidential race with more than 120,000 new donors his first week. Most weeks since, he has strained to bring in a few thousand.

O’Rourke’s plan not “to do large-dollar fundraisers” gave way by the end of the spring to plans for several such events. By May he was in New York holding a private reception for “hosts” who raised $25,000 or more for the event.

He is hardly alone.

Sen. Kamala Harris was in the Hamptons in August, where she took shots at Sanders’ Medicare for all proposal. That drew a rocket from the Vermont senator.

“I don’t go to the Hamptons to raise money from billionaires,” he scolded over Twitter. “If I ever visited there, I would tell them the same thing I have said for the last 30 years: We must pass a Medicare for All system to guarantee affordable health care for all, not just for those who can afford it.”

Harris’ fundraising was in the spotlight again a few days later when she hedged on whether she would join rivals at CNN’s Climate Crisis Town Hall on Wednesday. She had fundraisers scheduled that night. After activists took to social media to call her out, Harris accepted the CNN invitation.

As her experience shows, high-dollar fundraising can make for awkward optics, especially at a time when candidates have put political reform at the top of their agendas. At least seven presidential contenders have taken the “Reform First” pledge demanded by a coalition of groups led by the nonprofit End Citizens United, which promises strict new fundraising rules and ethics reform as the first bill they would push from the White House.

Most of them also took pledges to refuse help from lobbyists or super PACs. But the reformer image can be tough to project when candidates faced with a small-donation shortfall turn to intimate gatherings organized by corporate titans, or partners in big law firms, with considerable business before the federal government.

When an African American church-based political group brought thousands of young black Christians to a presidential forum in Atlanta this summer, some prominent candidates were absent due to “scheduling conflicts.” On their schedule: trolling for donors.

Joe Biden was making a pitch at the time to donors who noshed on mini crab cakes in the resort town of Rehoboth Beach, Del., where he owns a $2.7-million vacation home. Harris was in the seaside playground of Martha’s Vineyard, where donors feted her at the home of director Spike Lee. The co-chairs for that event each had to raise at least $10,000.

Sanders and Warren, meanwhile, were at the Black Church PAC event.

A few days later, organizers of a large Native American presidential forum were irked by the absence of Biden and Harris. The former vice president was in Washington’s Georgetown neighborhood, being toasted by donors at the home of Nelson Cunningham, whose lobbying firm represents several of the world’s largest corporations. Harris was scheduled to be in Los Angeles raising cash with the help of Hollywood execs. She patched into the Native American forum by Skype.

Both Biden and Harris have netted impressive numbers of small donors online. The same is true for South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg, who is also spending significant time on the big-money fundraising circuit.

Each has found, however, that building a small-donor movement is one thing; building a small-donor movement big enough to bankroll an entire national campaign is quite another.

The political price of spending all that time with establishment donors is not always clear.

“A lot of it has to do with the image the candidate puts out to the world,” said Sarah Bryner, research director at the Center for Responsive Politics. “Biden never made any claims to be a person like Bernie Sanders. He was vice president. He is a Washington insider. He hasn’t sworn off the same donations others have. … The people who are supporting him I just don’t think care that much.”

Much the same, she said, holds for Buttigieg. The calculus is more complicated for candidates like Harris and O’Rourke, who fashion themselves as political reformers.

Poor image isn’t the candidates’ only worry. All that hobnobbing with the elite is also a serious time suck.

“It really warps the candidate’s schedule,” said Jeff Weaver, Sanders’ senior adviser. “Your time is eaten up by other people with these donor calls and small events and traveling to these places to raise money. … Bernie Sanders spends more time talking to voters and packing town halls and rallies. The more voters hear him, the more small donors come. The more donors come, the more people come out to hear him. It becomes a system which builds on itself.”

Warren has been to 128 town halls. Her campaign’s selfie-taking machine is now legendary, logging 52,000 snapshots with voters. She has time to hang around after events that candidates darting off to fundraisers don’t. In Seattle last week, she stayed snapping selfies for four hours.

There has been no other presidential primary in recent history where two of the top three candidates run their campaigns by swearing off bundlers and private fundraisers with wealthy donors. That makes this election cycle a milestone for anti-corruption activists.

But they acknowledge big money keeps finding its way in, and not just in the form of a front-runner — Biden — who is unabashed about cozying up to big donors.

The Democratic super PAC Priorities USA is raising tens of millions of dollars for the general election using legal loopholes to accept unlimited amounts and keep the identities of many of its donors secret. Other groups on both sides of the aisle are using the same types of tactics. And the Democratic National Committee is requiring candidates who want to tap into its voter file, a key tool for campaigns, to show up at big-ticket fundraisers.

That led Warren to a rare uncomfortable place a week ago. On the stage at the party’s “I Will Vote” gala dinner in San Francisco, she spoke forcefully about rooting out corruption.

Among those in the audience? VIP donors who paid $50,000 for a table and entrance to a private reception.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.