A tale of two rallies: Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have similar ideas but competing paths to 2020 victory

FRANCONIA, N.H. — For progressive voters like Richard Poulin, the 2020 Democratic presidential primary offers an agonizing choice between two heroes of the left, Sens. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts.

Poulin, a New Hampshire store owner, was a devoted supporter of Sanders’ unsuccessful 2016 campaign. Now, he wonders whether Warren is in a better position to beat President Trump than Sanders.

“The most important thing to me is to get rid of Trump,” said Poulin. “It’s like choosing between two desserts.”

But for all their ideological similarities, Sanders and Warren are in many ways as different as ice cream and petit fours — one a reliable, simple classic; the other, a less familiar, refined taste.

A pair of rallies last week by the two candidates, only 11 miles apart on consecutive days in New Hampshire’s mountainous North Country, showcased their differences of style, tone and potential paths to the Democratic nomination.

Sanders spoke at a small-town opera house in Littleton to about 300 supporters, including many from his 2016 following who are crucial to his ability to win. Warren went to a splashier setting — a tony estate in Franconia with a spectacular view of the White Mountains — to address an audience of 700, which included not just die-hard supporters but also curious voters checking her out for the first time.

Their overarching messages were similar in calling for sweeping changes in the economy and political system — an agenda that some Democrats fear makes both of them too radical to win in a general election.

“What this campaign is about is not only defeating Donald Trump,” Sanders said. “What this campaign is about is transforming the government and the economy of the U.S. so that it works for all of us and not just the 1%.”

Warren’s take: “We’ve got an economy right now that just keeps working better and better for the bigger and bigger — the giants who have taken over one field after another — big ag, big tech, big pharma, big banking.”

Some progressive voters attended both rallies, and said their biggest fear is that Warren and Sanders will split the left-wing vote and clear the way for the more centrist Joe Biden, the former vice president who is widely regarded as the front-runner for now.

“Both Bernie and Elizabeth say they can beat Trump, and I believe that,” said Nancy Strand, a Sanders supporter in 2016 from Bethlehem who is now inclined to back Warren. “But somebody has to beat Biden first. If they split the progressive vote, Biden gets through.”

While both Warren and Sanders are targeting voters on the left, they are drawing support from very different demographic groups, early polling by Morning Consult suggests.

Warren’s coalition is older, better educated and more affluent. Sanders has stronger appeal to young voters, people without a college degree and the less affluent. That puts Sanders in competition with Biden for blue-collar voters.

The debate over reparations for slavery is getting new attention through the 2020 presidential race. For the descendants of slaves in South Carolina, it’s personal.

Warren has been steadily gaining on Sanders in polls over the last several months, but the rivals — who describe themselves as friends — have not taken potshots at each other. They were notably companionable when they appeared on the same stage in the second round of Democratic candidate debates.

New Hampshire is a key battleground because it holds the first primary, on Feb. 11, after Iowa holds the first nominating caucuses. Biden leads in most polls in New Hampshire, but it is the narrowest lead of all the early voting states.

Sanders and Warren hold a home field advantage because they come from neighboring states. But Sanders has the biggest advantage — and the burden of high expectations — because he won the New Hampshire primary in a blowout last time. His long-shot bid took off after he beat Hillary Clinton here, 60% to 38%, setting up a bruising contest through the primaries.

In Littleton, Sanders took the podium to loud chants of “Bern-ie! Bern-ie!” from adoring fans. The event had the feel of a revival meeting, with some call and response from an audience that had heard the Sanders sermon before.

Speaking about “Medicare for all,” Sanders asked, “Does that sound like a radical idea?” “No sir!” the crowd shouted back.

He asked about the goal of the healthcare system. “To make money!” the crowd roared.

Although Sanders has complained lately about polls and media coverage, he cited some survey results he liked: general election matchups that show him beating Trump.

Sanders’ audience included retirees with canes and young people with long, unruly hair. “That’s what my hair looked like a few years ago,” joked Sanders, who is balding at age 77.

For fans who wanted a selfie with their hero, it was not easy. Sanders, who clearly does not relish this staple of modern campaigning, took a few photos after the speech while shaking hands and working his way to the exit.

One of the lucky ones was Katie Malgioglio, a college student who drove four hours from Connecticut to see him.

“Bernie Sanders is the reason I’m so into politics,” Malgioglio said. “I would not be the person I am if not for Bernie Sanders.”

Warren’s crowd in Franconia the next day was more than twice as big, but she was not preaching only to the converted.

“I’m a fan but still undecided,” said Melissa Davis, a Plymouth lawyer who supported Sanders in 2016. “I’m a little torn. All the candidates are using his talking points and using his ideas. That’s what is making it difficult to pick someone.”

Warren sprinted across the manicured green lawn to the podium, a show of athleticism that belies her age — 70 — at a time when Biden’s age, 76, has been a campaign issue.

While Sanders’ rhetoric was often hortatory and broad, Warren’s speech began with a deeply personal account of her upbringing in Oklahoma and the financial insecurity her family faced — introducing autobiography in a way that Sanders rarely does.

Warren’s yarn culminated in her view of government as a force for good for middle-class Americans — at least until it came into the grip of special interests.

“It is 25 years of corruption in Washington that has brought us to this place,” she said.

She ticks through some of the many detailed plans that have been her campaign’s hallmark. She took fewer questions than Sanders after her stump speech but ended as she almost always does: She gave a selfie to every voter who got in a line that snaked across the grounds. According to her campaign, Warren spent an hour taking photos with about 400 people. They estimate she has taken nearly 45,000 selfies in total.

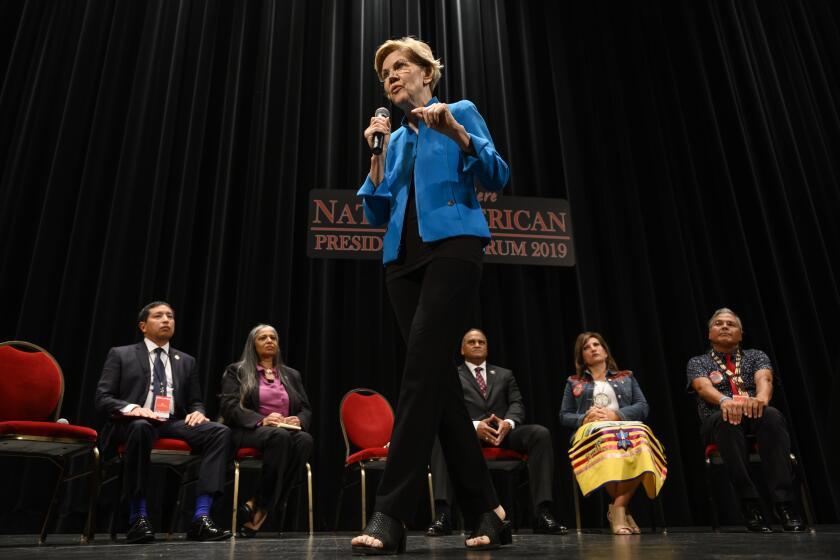

Sen. Elizabeth Warren offered a public apology over her past claim to tribal heritage, tackling a political liability in the 2020 presidential election.

The combination of Warren’s personal touch and policy detail was enough to win at least one convert in Franconia. Sue Manah Buteau — a strong Sanders supporter in 2016 — attended both rallies with her husband, unsure whom to back in 2020. They were both swayed by Warren.

“What I liked best about her is she shared her personal story, her roots, her own struggles growing up,” said Buteau, a retired teacher from Lancaster. “She has the kind of energy that could really carry her through the campaign.”

What’s more, she said, Warren is more likely to win support from the Democratic Party establishment than Sanders, who is still an independent and has often criticized the party.

That remains a sore point with Sanders supporters who believe the Democratic National Committee skewed the 2016 primary competition in favor of Clinton and against Sanders.

Kate Goldsborough, an actress and stylist in Littleton who also attended both rallies, considers Warren too “mainstream” for her taste, and is worried Sanders will get undercut again by the party establishment.

When she asked Sanders about the prospect at his Littleton event, he tried to focus on his campaign message.

“I’m looking forward, not backward,” he said. “I’m not naive. We are taking on the entire establishment. I need your help.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.