Trump wants to keep his tax returns private, asks courts to stop California law

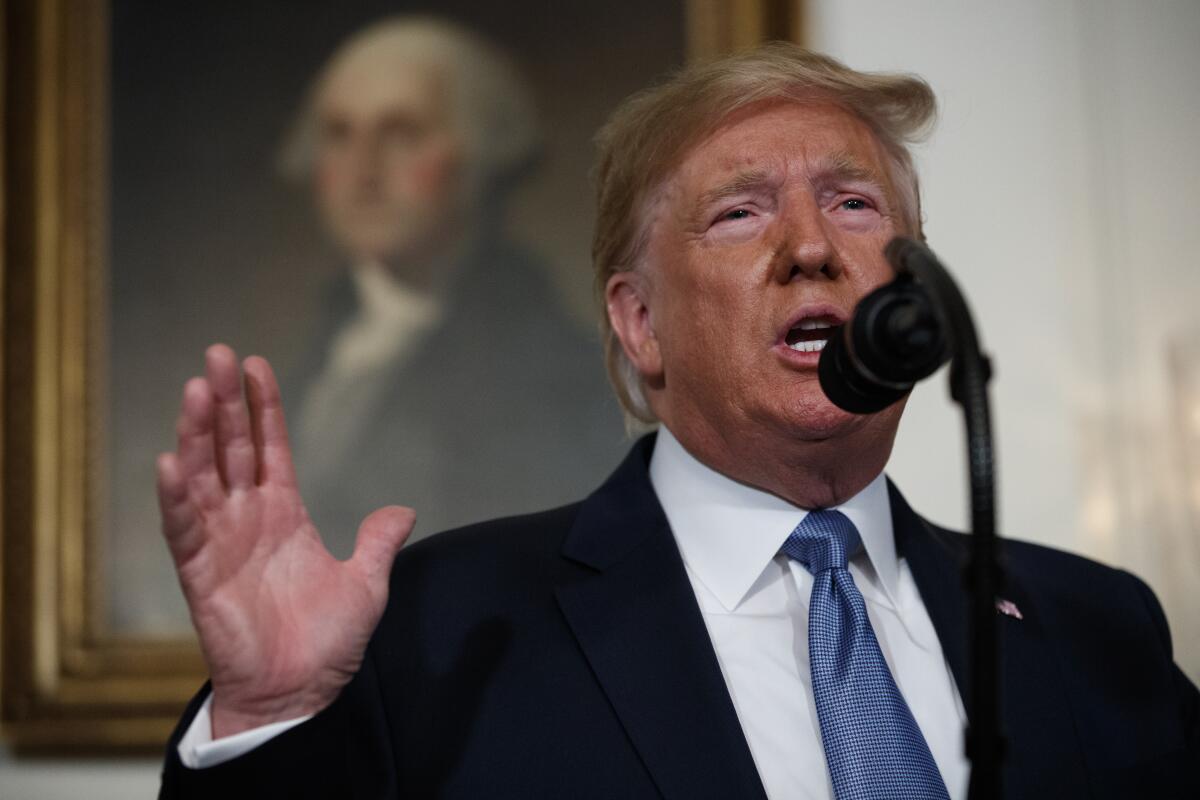

SACRAMENTO — California’s first-in-the-nation law requiring presidential primary candidates to release their tax returns or be kept off the ballot was challenged in federal court Tuesday by President Trump, the man who inspired its passage and whose attorneys argued that state Democratic leaders had overstepped their constitutional authority.

The lawsuit, filed in Sacramento, came exactly one week after Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the legislation. Two other legal challenges preceded the one by Trump and his 2020 reelection campaign. A separate effort by the state and national Republican parties and several California GOP voters was also filed in federal court on Tuesday. All of the lawsuits struck a similar theme by insisting California cannot impose limits on ballot access for presidential hopefuls.

“The issue of whether the President should release his federal tax returns was litigated in the 2016 election and the American people spoke,” Jay Sekulow, an attorney for Trump, said in a written statement. “The effort to deny California voters the opportunity to cast a ballot for President Trump in 2020 will clearly fail.”

The president has steadfastly refused to offer the public a glimpse of his annual income tax filings with the Internal Revenue Service, frequently insisting — without any proof — that he cannot do so while the returns were the subject of an IRS audit. Most of the Democrats now vying for their party’s nomination to challenge Trump next fall have already released some of their tax returns, though not all have met California’s standard of producing five years’ worth of information.

The Trump campaign and Republican Party sued California on Tuesday over a new law requiring presidential candidates to release their tax returns to run in the state’s primary.

Senate Bill 27, which passed the California Legislature on a party-line vote last month, took effect as soon as Newsom signed it. It imposes the tax disclosure rule on presidential and gubernatorial candidates, and stipulates that only the names of candidates who comply will be printed on the statewide primary ballot. Because the state has moved up its presidential primary to early March, the deadline for submitting the tax documents is in late November.

The 15-page court filing alleges five counts of illegal action by California officials in enacting the tax returns law. Trump’s attorneys contend state can only issue “procedural regulations” governing its election for president. Even if the state did have a role, the attorneys wrote, California’s law “does not serve a compelling state interest and, in any event, is not narrowly tailored to that interest.”

National and state Republicans called the California law “a naked political attack against the sitting President of the United States” in their lawsuit. They wrote that SB 27 “effectively disenfranchises voters by denying their right to associate for the advancement of political beliefs and effectively cast a vote for the otherwise qualified candidate of their choosing.”

The author of SB 27, state Sen. Mike McGuire (D-Healdsburg), worked with a group of constitutional scholars when drafting the bill. He derided the lawsuits as “frivolous” and unlikely to prevail.

“It comes as no surprise that President Trump would freak out at the prospect of presidential transparency and accountability, but he will need to get used to it,” McGuire said in a statement.

Newsom, who provided access to his tax returns in the 2018 election and has routinely criticized the Republican president for his failure to do the same, said Tuesday that a lawsuit was unnecessary.

“There’s an easy fix Mr. President — release your tax returns as you promised during the campaign and follow the precedent of every president since 1973,” Newsom said on Twitter. The governor’s statement overlooks that President Ford refused to release his tax returns in 1976, though every other president in the intervening years has, until Trump.

Two other lawsuits have challenged the California law on similar grounds to the GOP-led effort. One was filed Monday on behalf of a handful of state voters by the conservative-leaning group Judicial Watch. The other was filed last week by Roque “Rocky” De La Fuente, a California businessman who has run several low-profile campaigns for president.

The four separate federal lawsuits were joined Tuesday by a challenge filed in the California Supreme Court by Jessica Millan Patterson, chairwoman of the California Republican Party. In that challenge, Patterson argues that the state’s own Constitution requires elections officials to include any candidate on the presidential ballot who meets national criteria — a process strengthened and made more transparent by a different law Newsom signed last week.

Assemblywoman Melissa Melendez (R-Lake Elsinore), a staunch supporter of Trump and one of those who filed the federal lawsuit with GOP officials, said Newsom chose politics over the advice of former Gov. Jerry Brown, who vetoed a similar measure in 2017 and raised concerns about its legality.

“Gov. Newsom doesn’t seem to care,” she said. “This is not how America works. ... It’s still kind of shocking that this is the point we’re at now.”

Legal scholars have offered mixed opinions as to the constitutionality of SB 27. Some suggested that because state legislatures are given wide berth by the U.S. Constitution in choosing presidential electors, the law could be seen as a logical extension of that power. Others, however, said the law could be thrown out on the same grounds as previous efforts in other states to link a congressional incumbent’s ballot access to how many terms the person had already served in the House. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected such restrictions in a 1995 ruling.

Action on Trump’s legal challenge could be swift, when measured against other complex cases filed in the federal courts. Richard L. Hasen, a UC Irvine election law professor, said the best that plaintiffs could hope for in the current presidential election cycle is a preliminary injunction that stops the law from taking effect this fall. “I think these are complicated issues,” he said. “The final question might not be sorted out for a couple of years.”

Hasen noted that the lawsuits raise multiple issues -- from constitutional power to the rights of political parties and voters -- and that taken as a whole, they pose a daunting challenge for state officials in the coming months.

“If I had to bet, I’d think that one or both of those arguments could convince a court to strike it down,” Hasen said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.