Indian Americans, a rising political force, give $3 million to 2020 presidential campaigns

Indian Americans are a sliver of the nation’s population but a growing political force. They have contributed more than $3 million to 2020 presidential campaigns — more than the coveted donors of Hollywood.

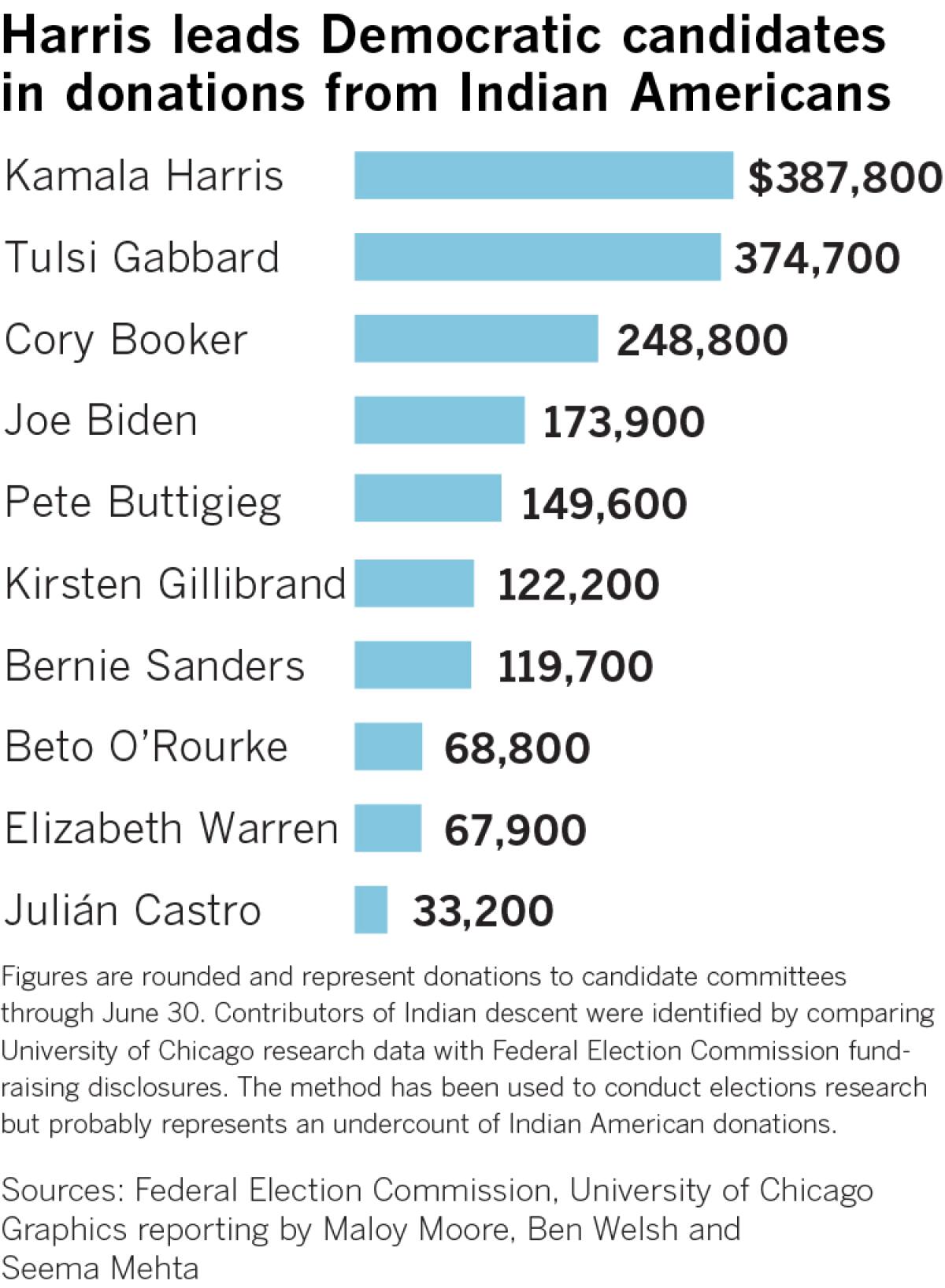

On the Democratic side, they are largely split among three candidates who have ties to their community: Sen. Kamala Harris of California, whose mother was born in India; Rep. Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii, a practicing Hindu; and New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, who counts a large Indian American population among his constituents.

The trio has targeted these wealthy donors from coast to coast. At a recent fundraiser, Harris touted her ties to her mother’s homeland as she sought donations from its descendants.

“My grandfather, having been a freedom fighter in India and a very progressive person, put my mother on a plane, a transcontinental flight, which was unheard of in those days, 1959, to go and study at Berkeley,” Harris told about 100 people in the backyard of a Washington mansion.

Harris, who is the only major presidential candidate with Indian heritage, has raised more than $387,000 from the Indian American community for her 2020 bid, more than any other Democrat in the race, according to a Times analysis of disclosure forms filed by the campaigns. But the senator, who is also of Jamaican descent, is not an overwhelming favorite of Democratic donors: Gabbard was a close second with more than $374,000.

Indian Americans represent just over 1% of the U.S. population. In recent years, they have grown increasingly politically active, donating more to candidates and running for office. Reflecting the community’s leftward tilt, two-thirds of the more than $3 million donated throughout the 2020 election cycle has gone to Democrats, according to a Times analysis of fundraising reports released July 15.

Indian Americans have also donated more than $1 million to committees supporting President Trump. The incumbent has the benefit of being able to accept six-figure checks into a joint fundraising committee with the national and state Republican parties. The Democratic candidates are limited to donations of up to $2,800 for the primary and $2,800 for the general election.

Though Indian American voters strongly trend Democratic, a vocal minority has embraced the president. They cite his positions on the economy and fighting Islamist terrorism, an issue their motherland has struggled with for decades.

“On foreign policy, on protection of industry, on creating jobs ... he has delivered on practically everything he promised,” said Shalabh “Shalli” Kumar, founder of the Republican Hindu Coalition.

The Times identified contributors of Indian descent using fundraising disclosures and a database of names compiled by Diane Lauderdale, a social scientist at the University of Chicago. The list was derived from government surveys in which people provide their last name and a country of ancestry. The method is used by top universities to conduct elections research. However, it cannot identify all Indian Americans, so The Times’ analysis probably represents an undercount.

Harris made headlines in the U.S. and India in 2016 when she was elected the first Indian American senator, but she has work to do among donors in the community, experts say.

“A fair number of Indian Americans are excited by her candidacy, but she’s still not tapping into that donor base nearly as much as she could,” said Karthick Ramakrishnan, a UC Riverside professor who studies Asian American politics.

Ramakrishnan and others note that no ethnic community is monolithic and that sharing one’s skin color, religion or language does not guarantee support.

But some in the Indian American community say Harris’ Indian descent is not as well known as it could be partly because the senator — who attended a historically black college and joined an African American sorority — has embraced her blackness in a way that overshadowed her South Asian heritage.

One example they point to was during a June debate when she confronted former Vice President Joe Biden over his past opposition to some forms of busing for school integration.

“After the episode in the debate, where she pointedly said, ‘I’m the only black person on the stage’ to Biden … there were a number of people who said, ‘What happened to the other part of her?’” said Shekar Narasimhan, chairman of the AAPI Victory Fund, a super PAC aimed at mobilizing Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

Narasimhan, who is not aligned with any candidate, said Harris had successfully raised money from Indian Americans, or Desis, during runs for attorney general of California and the Senate. But she had not been as much of a face at Indian American events until last year, while other candidates have had a more consistent presence, he said.

“People think she got elected to Senate and she forgot about us,” he said.

Harris has spoken about how her upbringing included aspects from both of her parents’ cultures, but how her mother raised her and her sister as black girls because that was how they would be viewed by society. “She was determined to make sure we would grow into confident, proud black women,” Harris wrote in her autobiography, “The Truths We Hold.”

Manan Trivedi, a physician who hosted Harris’ Washington fundraiser with his wife, Surekha, said they were drawn by Harris’ Indian heritage and her being the child of immigrants: “We have two little girls, ages 5 and 9, and I want them to able to look up to the president and relate.”

But he said they decided to support Harris because they believe she is “whip smart” and best positioned to defeat Trump. “That was the No. 1 criteria,” said Trivedi, 45.

Gabbard nearly tied Harris in donations from Indian Americans through June 30, raising almost 10% of her total haul from individual donors from the community — the highest share in the field.

Gabbard is not well known nor Indian American, but she has long been a favorite of Desi donors because of her devout Hinduism and staunchly pro-India foreign policy. She has practiced the religion since her teens and was the first Hindu elected to Congress. Gabbard is also aligned with controversial Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the ruling, Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party.

“I’ve known her for a long time,” said Bharat Barai, a Chicago-area oncologist who is a registered independent. “Putting apart religion, she has served her country well at a young age. She’s a leader from Hawaii, and she served twice in Iraq, so she’s a veteran. I think she has good social ideas on how to work for the people.”

Barai said that if Gabbard is not the nominee, he could see supporting Biden or Harris. His three daughters favor California’s junior senator, but Barai noted that the former vice president has decades-long ties to the Indian community.

Biden has made gaffes — notably telling an Indian American man in 2008 while talking about the community’s growth in Delaware: “You cannot go to a 7-Eleven or a Dunkin’ Donuts unless you have a slight Indian accent. I’m not joking.” But that moment is largely overshadowed by his efforts to strengthen the U.S.-India relationship, including fighting as a senator for a nuclear deal.

Biden, who joined the 2020 field in May, has raised more than $173,000 from Indian Americans, a number expected to rise after fundraisers last week in California, home to the largest number of Desis in the nation.

One Bay Area donor, who asked for anonymity to speak candidly, said he donated to Harris’ earlier campaigns but is backing Biden.

“The Indian community sees him as one of our leaders,” he said, recalling Biden and President Obama lighting oil lamps to celebrate Diwali, or the festival of lights, at the White House. “Kamala, on the contrary, has taken another direction. That’s her personal choice, only to highlight her African American heritage and not even show interest in her Indian heritage.”

Booker has more than $248,000 from Indian American donors. New Jersey has a large population of Desis, and Booker has long maintained relationships with the community, showing up at festivals and backing Indian American candidates.

“He’s very genuine. He talks about a unifying message,” said Sangeeta Doshi, a Booker donor and a Cherry Hill, N.J., councilwoman whom the senator endorsed.

She recalled attending an Indian American PAC’s event in Washington for newly elected Desis and Booker being the only non-Indian speaker there.

“He’s just very dynamic,” Doshi said. “Harris was an amazing speaker too but he’s our senator. I’ve had more interaction with him.”

Harris supporters are confident that as the field winnows and if she continues to gain in polls, skeptical donors will coalesce behind her.

“People are moving to her side now,” said Ashok Bhatt, co-host of a June luncheon for Harris in San Francisco. “I’m going to put on more events for her to let people know we have confidence in a woman who can hold power, hold the White House, for the first time.”

It may take a little more flattery on Harris’ part.

At her May fundraiser in Washington, which was closed to the media, a man asked her to take a pledge, according to video of the event provided by an attendee, who didn’t want to be named for fear of running afoul of the campaign.

“When you become president, we want … your first foreign visit to go to India instead of Jamaica,” the audience member said.

Harris laughed broadly but didn’t commit.

Times staff writer Ben Welsh contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.