Capitol Journal: Gov. Brown travels the globe talking about climate change. He should focus on this basic program at home

Reporting from In Sacramento — Gov. Jerry Brown traipses all over the world trying to save the planet from global warming. But he needs to salvage one basic environmental program here at home.

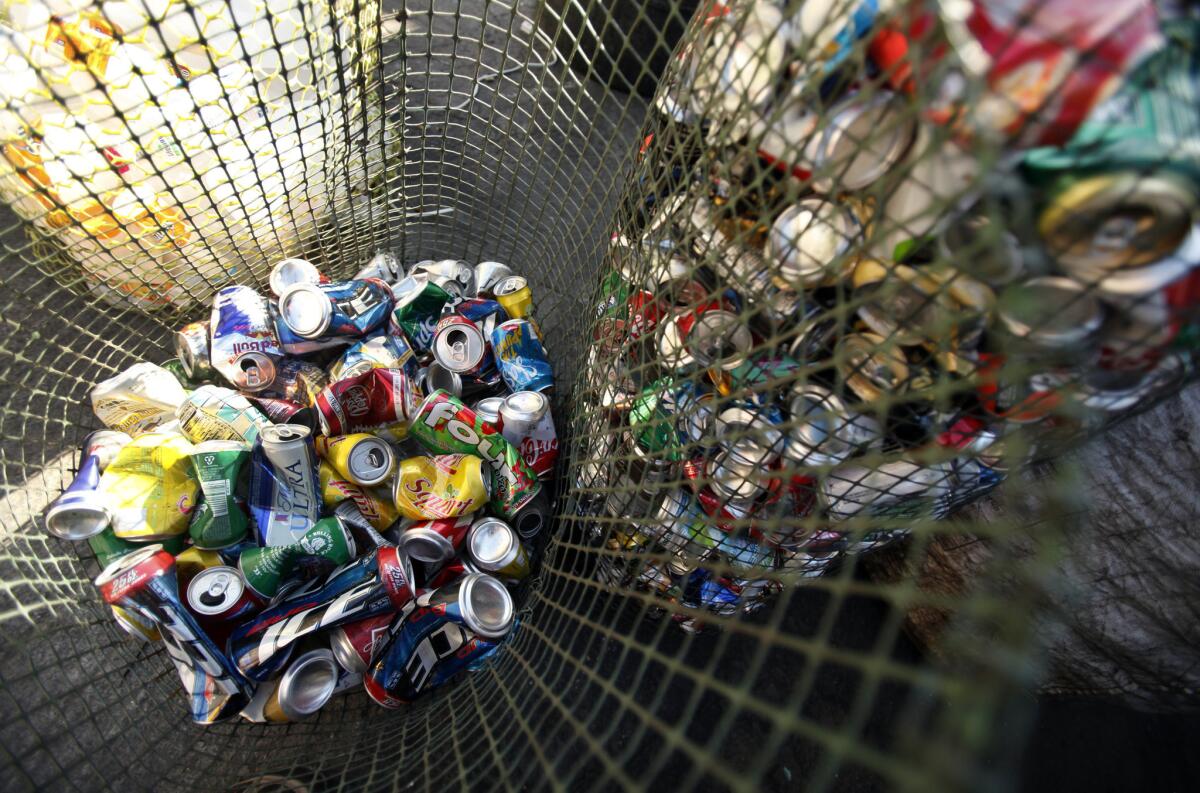

That’s the widely popular beverage container recycling program. People use it and feel good about themselves, particularly younger generations that have grown up separating recyclable cans and bottles.

Leave the containers in a bin on the curb for trash haulers. Or cart them to a recycling center and collect the nickel a piece — maybe a dime for larger ones — that was deposited when the beverage was bought at a store.

This is the old Bottle Bill that the Legislature fought over for 20 years until it passed a complex, convoluted compromise in 1986.

Generally, the bill has been a huge success over the years. Supporters say it has prevented nearly 1 million tons of plastic, glass and aluminum from being littered or tossed into landfills. Californians recycle more than 50 million containers a day.

But the program itself needs some recycling. It’s not generating enough money, in many cases, to make recycling pay.

The way it works is rather byzantine: The beverage distributor pays the nickel to the state, then recovers it by passing the cost onto the store. The store recoups the nickel by adding it to the product’s price.

The state uses the distributor’s money to pay a nickel to the local government or private operator for each container it collects at curbside — or reimburses the recycling center that gives the consumer back his deposit.

Because not all containers the state receives nickels for wind up in recycling, the state builds up a surplus. It’s supposed to be used to cover the handlers’ red ink when recycling doesn’t pencil out.

And it’s not penciling out now, primarily because scrap value has dropped for plastic and glass. With oil prices down, it’s cheaper to make new plastic bottles than to recycle old ones. Aluminum still brings a good price, but fewer cans are being made from it. Plastic dominates.

The state isn’t covering everyone’s red ink, however, even if its recycling fund has a $250-million surplus. The state says it doesn’t have the flexibility to dip in without legislation. Recycling activists blame a state calculating snafu.

That’s the problem in a nutshell.

Roughly 560 recycling centers have closed in the last 15 months. That’s 25% of the total. Recycling rates have dropped from 85% of containers to less than 80%, still pretty impressive. More than 1,000 employees have been laid off.

“It means that 2 million more containers are littered or landfilled every day, including more than 1 million plastic bottles,” says Mark Murray, executive director of the activist Californians Against Waste.

“The Pacific Ocean does not need any more plastic pollution. This is insane,” says Jared Blumenfeld, who once ran San Francisco’s recycling program.

This is not earth-shattering. With all the problems in California and the country, a bottle tossed here or there isn’t going to ring alarm bells.

But if state government can’t make a core environmental program work right, what hope is there for its high-profile efforts to get off fossil fuel and rely more on renewable energies — and to help stop the polar icecaps from melting?

Brown acknowledges that recycling is a tool in fighting global warming.

“Combating climate change requires strategies to reduce the amount of landfilled waste and increase recycling,” the governor stated in his budget proposal in January.

“Recycling reduces greenhouse gas emissions by lessening the need for natural resource extraction” — pumping the oil used in plastic, for example — “saving energy in the manufacturing of new products and minimizing landfill emissions.”

But the recycling program “faces significant challenges,” Brown continued. It “requires comprehensive reform.”

OK, recycling boosters ask, where’s the governor’s reform proposal?

They tried to pass a simple bill last year to patch up the program, but Brown warned he’d veto it. He called for major reform.

“The governor told us to wait,” recalls Assemblyman Richard Bloom (D-Santa Monica). “So we waited and waited and waited. And he hasn’t been forthcoming.”

The governor did issue a paper in January outlining his recycling goals. For one thing, he’d like to include wine and liquor bottles in the program. Now only beer and soft drinks require deposits. Sure, why not? Well, the winemakers and booze distillers don’t want to be bothered, for one.

Brown doesn’t have any actual legislation in print.

Bloom is pushing a bill that, among other things, would eliminate a requirement that grocery stores pay $100 per day or take back the old containers themselves if there isn’t a nearby recycling center. They don’t want those old filthy bottles and cans anywhere near their food.

State Sen. Bob Wieckowski (D-Fremont) has a bill that basically would junk the whole program and create a new recycling system. And he’d include wine and liquor bottles.

Murray says everyone is thinking too much. Just take $30 million from the recycling surplus, he urges, and fix the current problem.

“Consumers are paying a nickel and can’t find a recycling center,” he says. “I’m concerned there might be a consumer rebellion. This is not a time the state should be trusting the public’s faith.”

Much of the public doesn’t care what Brown says about global warming in China or France. But many do care about getting their nickels back near home.

Follow @LATimesSkelton on Twitter

ALSO

While California spends liberally, the governor talks like a penny-pincher

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.