Will billionaire Tom Steyer’s big bet on young voters pay off in midterm election?

Tom Steyer made his fortune as a hedge fund manager taking risky bets in volatile conditions. In this year’s high-stakes midterm election, the billionaire turned political activist is making another costly wager on one of the most historically unreliable groups of voters: young people.

Steyer, whose advocacy group NextGen America has pledged $33 million to engage young voters in 11 states — $3.5 million alone in California — insists that his is no quixotic venture. He and others believe that the only hope Democrats have of taking control of Congress is to inspire new and infrequent voters to cast ballots as a check on President Trump.

Steyer, 61, roamed the Cal State Fullerton campus recently — clipboard in hand, shirt sleeves rolled up. He approached 18-year-old Marina Lieu, who told the graying man in front of her that voting didn’t interest her.

His head drooped. He heaved a sigh.

Then he leaned in close and lowered his gravelly voice to a near-whisper. “You can change this world, or it can be run by a bunch of arrogant, entitled, rich white old men.”

Democrats, angling for the 23 seats they must net on Nov. 6 to take back the House, are pinning their hopes in part on young voters, and for good reason. Millennials, those born between 1981 and 1996, lean harder left than older generations. They’re more racially diverse, less likely to approve of Trump, and are due to become the country’s largest bloc of eligible voters in a matter of months.

But they tend not to vote.

“If the House stays Republican, I think we’ll consider this year a failure,” Steyer says.

If history is a guide, success is at best uncertain.

Voters aged 18 to 34 have cast ballots at lower rates than any other age group in every midterm election for the last 40 years, according to census data. Fewer than 1 in 4 young adults voted in 2014, the last midterm election.

Want to vote in the Nov. 6 elections? Here’s how to register »

Young people are highly mobile, making them harder and more expensive to reach. For campaigns, “That’s a pretty low return on investment,” says Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, a Tufts University expert on the youth vote. “Once that perception is settled, it’s really hard to change strategies around it.”

Her research center has ranked the top 50 congressional districts where a surge in youth voters could make a difference in close races. Eight are in California.

The picture here has been even more grim. In 2014, only about 15% of California’s 1.8 million registered young voters bothered to turn out in November, according the California Civic Engagement Project.

“Is that a problem or is that an opportunity?” Steyer said in an interview. “It’s the most diverse group in American history, biggest group, most progressive...and they don’t vote, so let’s ignore them? Really?”

Steyer is probably better known for his $40-million petition campaign to impeach Trump, which 6 million Americans have signed. He says he considers the youth vote problem an existential crisis akin to climate change, his signature issue. “If you don’t solve it, you don’t have a democracy,” he said.

NextGen has been on the ground in California’s most competitive congressional districts for months and has hired dozens of organizers, many of them students, to take on the Sisyphean task of convincing college-age adults that their voices matter.

Unlike the slick “Rock the Vote” campaigns or Taylor Swift’s viral call-out on Instagram, NextGen’s efforts to boost participation are built on direct contact: peers reaching out in the quad or making appeals in classrooms. Steyer has organizers on more than 400 campuses nationwide; 20 are in California, where they’ve registered more than 27,000 voters.

He bills it as the largest youth mobilization effort ever, and no group on either side of the aisle appears to be matching his efforts.

Related: See the results of the most recent USC Dornsife/L.A. Times polls »

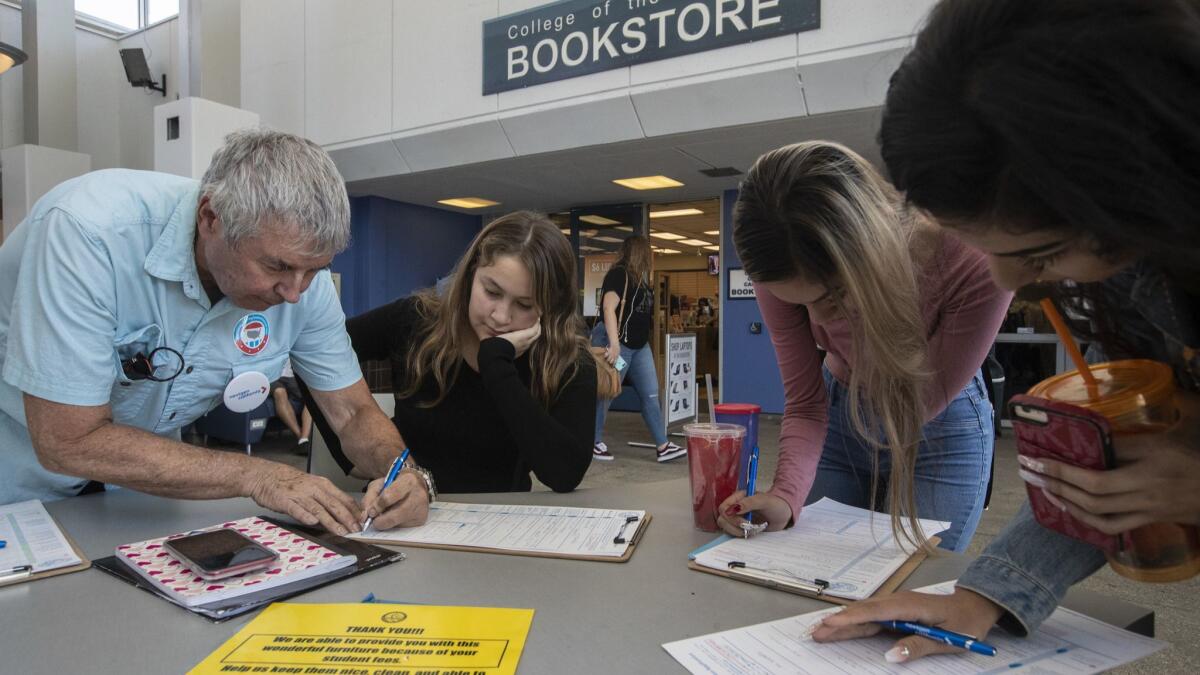

Daniel Nieto, 18, is one of his foot soldiers. On a warm afternoon recently, Nieto stood outside the bookstore at College of the Canyons in Santa Clarita, a few miles down the road from GOP Rep. Steve Knight’s office, beckoning his classmates with free swag and voter registration forms.

“When in doubt, fill it out,” was his frequent refrain to students unsure if they were registered.

Nieto, who works part time as a NextGen fellow, says the apathy he sees from classmates is familiar. “A lot of them have the same attitude that I used to have, and I can see they don’t think anything affects them,” Nieto said.

These days, he knows how to tailor his elevator pitch for democracy, pointing out the low number of congresswomen to female peers and talking about his struggle with tuition costs. If someone is in a hurry, he offers to walk them to class.

Jordan Stadler, 21, didn’t need much convincing that day. She bypassed NextGen’s photo booth stocked with Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump masks and put down her art portfolio to fill out a registration form.

A political science class she took taught her the importance of the midterm election. She plans to vote for the first time in November and favors Katie Hill, a millennial Democrat who’s challenging Knight. She wants to send a message to politicians that “things need to change.”

Stadler’s friends often tell her there’s little point to voting. “In a way, that’s true because one single vote isn’t really going to tip the balance to either side,” Stadler said. “But if a large group of us votes, I think that could make a difference.”

There are indications that young people like Stadler are more tuned in this year.

In the most recent survey of young voters by Harvard University’s Institute of Politics, 37% of those younger than 30 said they’d “definitely be voting” on Nov. 6, a jump from 2014, when just 23% said the same. An analysis by Democratic data firm TargetSmart suggested an uptick in young voter registration nationwide since this year’s school shooting in Parkland, Fla., launched a wave of youth protests demanding stricter gun laws.

In tight congressional contests, the sole focus of NextGen’s efforts in California, interest seems to be even higher.

A Times analysis of state voter data provided by Political Data Inc. shows that while voter turnout overall in the 2018 primary was up 50% over 2014 levels, turnout among youth aged 18 to 34 more than doubled. In the four Orange County congressional districts deemed some of the most competitive in the country, the figure tripled.

Another NextGen fellow, 20-year-old Kennedy Wilson, spent 15 minutes in front of a criminal justice class at Cal State Fullerton.

A politician’s entire job is to get reelected, Wilson told about 100 students. “If they realize that our voting bloc really cared...they would have to listen to us.”

She collected 30 voter registration cards.

While Wilson spoke, Miguel Santiago scrolled CNN’s website on his laptop to read about competitive House and Senate races, and looked up the definition of “toss-up,” a term to describe contests that are virtually tied. He registered last year, on his 18th birthday.

When Trump was elected president, Santiago was too young to vote. “It wasn’t my choice,” said Santiago, who lives in an immigrant-heavy neighborhood in GOP Rep. Dana Rohrabacher’s coastal Orange County district.

The oldest of six children, Santiago says he works about 40 hours a week at two jobs to help his family but makes time to prod his friends to register and vote, asking for screenshots as proof. Most of them aren’t interested.

On the day he visited Cal State Fullerton, Steyer recited to any teen who would listen the number of days until the election — 27 — and in a bid to relate, added his children’s ages: 24, 26, 28 and 30.

Most brushed him off, claiming they were already registered. Steyer wasn’t so naive as to believe them all.

“It’s a pain in the ass,” he said of the work. Running a youth turnout program takes resources, personnel and training, he added, and even then some conversations can be “profoundly unsatisfying. But that’s the way it goes.”

Still, he had planted the seeds for small victories he may not have been aware of.

Lieu, the skeptical student Steyer had approached, said later their encounter had stuck with her. She now plans to vote. Lieu said Steyer opened her eyes to how old, rich, white men were making decisions for her generation.

She was surprised to learn that Steyer himself was one of them.

Coverage of California politics »

Will California flip the House? The key races to watch »

For more on California politics, follow @cmaiduc.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.