Can a federal government scientist in California convince Trump that climate change is real?

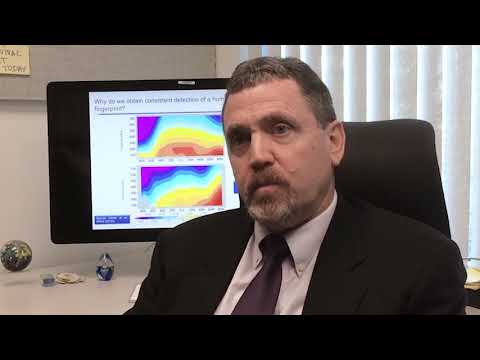

Ben Santer at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory east of San Francisco has become more vocal over the years in hopes of beating back claims that climate change isn’t real.

Reporting from Livermore — In the two decades since Ben Santer helped write a landmark international report linking global warming and human activity, he’s been criticized by politicians, accused of falsifying his data and rewarded with a dead rat on his doorstep.

He describes it as “background noise,” and he tries to tune it out as he presses forward with his research from a dim office the size of a walk-in closet at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory east of San Francisco. But the presidential election could crank up the volume for Santer and his colleagues: As federal government scientists, their new boss will be President-elect Donald Trump, who once described global warming as a hoax.

“Imagine, if you will, that you devoted your entire career to doing one thing. Doing it as well as you possibly can,” Santer said. “And someone comes along and says everything you’ve done is worthless.”

Trump’s victory sent shockwaves through the environmental community, but fears are particularly heightened among scientists who are employed by the federal government or rely on the data it generates. There are concerns that younger generations may avoid working for U.S. agencies or decide not to focus on climate change because they don’t see a future working in the field.

The election may have already had a chilling effect: Some working in national laboratories declined to speak about the impact the next administration could have on research they consider to be crucial to the fate of the planet.

Santer has responded differently. Although he’s soft-spoken in person, the 61-year-old scientist has become more vocal over the years in hopes of beating back claims that climate change isn’t real. Noticing the grim mood in his office after the election, Santer wrote an essay that he forwarded to friends to post online.

“This is not the time for despair,” wrote Santer, who is as meticulous with his words as colleagues say he is with his research. “It’s time for leaving the sidelines and entering the public arena.”

Perhaps, he said, incoming officials can still be convinced of the science to which he’s dedicated his life.

“Maybe there are people in the new administration who are willing to sit down and be educated and have a conversation,” Santer said. “I have to hope that there are those people.”

While Trump has pledged to keep an “open mind” when it comes to addressing climate change, he’s also expressed doubt about the scientific consensus on the topic. His choice to lead the Department of Energy, which oversees national laboratories like the one where Santer works, is former Texas Gov. Rick Perry, who once suggested abolishing the department altogether. He’s also described climate science as a “contrived phony mess.”

Scientists have viewed other actions by the Trump transition team with alarm, such as a request for the names of department employees who have worked on climate issues.

“They can do a lot of damage in a short period of time,” said Andrew Rosenberg, director of the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists. The organization is working on a secure channel for government employees to report alleged attempts by the incoming administration to interfere with their research.

Scientists also worry they’ll lose critical information streams from federal agencies such as NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, where Trump and congressional Republicans will manage personnel and determine funding.

“In the current administration there is support ... for climate science, and a respect for its findings,” said Michael Mann, a professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University. “I fear both will simultaneously evaporate in an anti-science presidential administration.”

A spokesman for Trump’s transition team did not respond to a request for comment about whether or how the federal government will support climate change research under the new administration.

National laboratories could prove to be a flashpoint in the brewing tug-of-war between California and Trump. Although Livermore is better known for its nuclear weapons research, there are also 50 researchers, computer scientists and software engineers focused on climate change, with $16 million in federal funding backing them.

“They’re concerned that they could be blacklisted,” said Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-Dublin), whose district includes Livermore. Swalwell wrote a letter with 26 congressional colleagues pledging to protect scientists in national laboratories, perhaps with legal action.

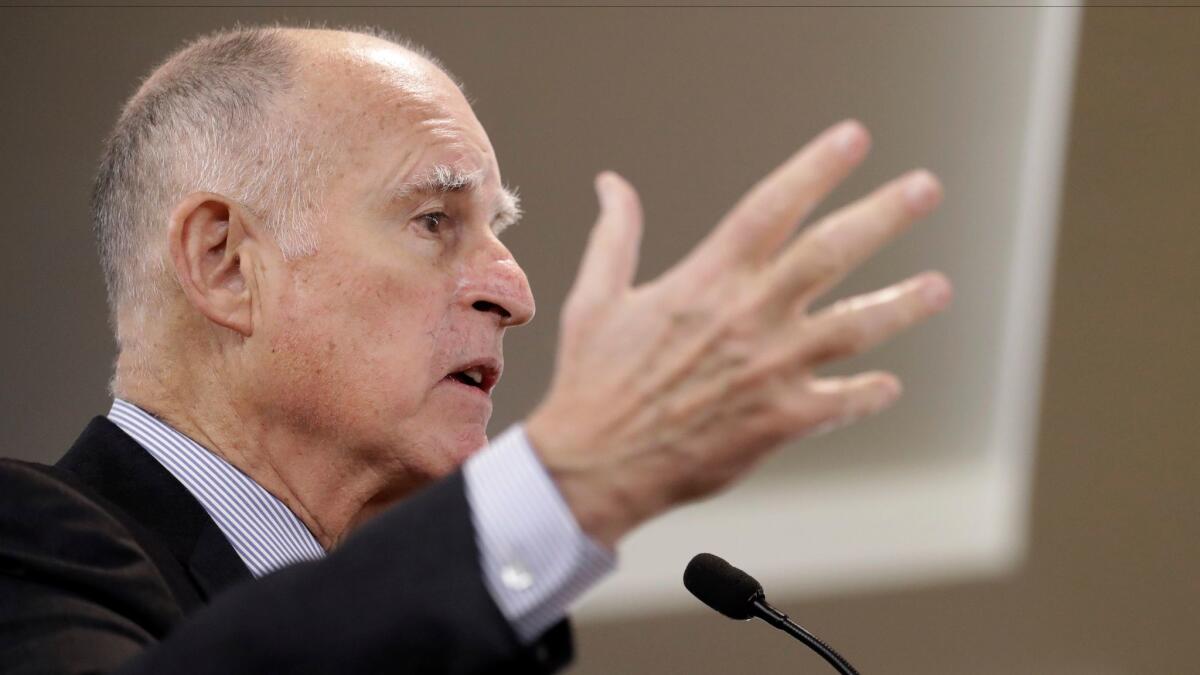

Because the laboratory is managed in a partnership with the University of California, Gov. Jerry Brown has promised to protect their work as president of the Board of Regents.

“I am going to say, ‘Keep your hands off. That laboratory is going to pursue good science,’ ” Brown said in a Dec. 14 speech at a science conference in San Francisco.

“And, if Trump turns off the satellites, California will launch its own damn satellite,” he added. “We’re going to collect that data.”

Santer has spent years examining that data. His specialty is “fingerprinting,” or identifying the causes of global warming. For example, an increase in the sun’s output could increase the planet’s temperatures, but in a different way than greenhouse gas emissions from cars and factories.

The ultimate prize, he said, is “the sense that maybe once or twice in your scientific career, you got one tiny piece of the puzzle that nobody else in the world has.”

Santer went to Madrid in 1995 to help write the second report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which said that “the balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate.”

“That sentence changed my life,” Santer said. He went on to become a MacArthur fellow and a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

Santer also became a target, as industry-backed groups attacked his research.

The goal of these campaigns is to “create the appearance that there’s still a ‘scientific debate’ over the existence of global warming,” said Erik Conway, the co-author of “Merchants of Doubt,” which chronicled attempts by industry to undermine scientific findings. “And that debate has been over within science since the 1990s. What the fossil fuel lobby doesn’t want is the public debate to shift from science to solutions, because solving man-made global warming means the end of their current business models.”

It was a disorienting experience for Santer, who remembers his first time testifying before Congress as terrifying.

“It did not feel comfortable or natural for me to be in public settings,” he said.

But instead of retreating, Santer decided to speak out more, viewing that as part of his responsibility as a climate scientist. He said he tailored a research paper to combat attempts by Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) to cast doubt on whether the planet was significantly warming.

But Santer knows the playing field is uneven. While his research gets published in scientific journals, politicians are invited on popular late-night shows, like when Cruz chatted about climate change with Seth Meyers in March 2015.

“I would love to have set the record straight on Late Night with Seth Meyers,” Santer deadpanned.

Santer said scientists need to push against misinformation, even if it comes from the federal government that issues their paychecks. And communication is key, he said.

“Why do you think ‘Make America Great Again’ worked?” Santer said. “My theory is the repetition. A simple message, repeated again and again and again.”

He added, “There’s an important lesson there for climate scientists. Somehow we’ve got to find an equally effective way of communicating the message again and again and again.”

Follow @chrismegerian on Twitter

ALSO

Trump brings Koch network’s green-energy foes from the fringe to the center of power

Trump seems ready to fight the world on climate change. But he’s likely to meet resistance

Updates on California politics

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.