From oil refineries to solar plants, unions bend California climate change policies in their favor

Reporting from Sacramento — No contour of California’s vast landscape inspires such passionate devotion as its coastline, so state lawmakers recoiled when President Trump announced in April that he wanted to expand offshore drilling. The outrage was channeled into a proposal for preventing any new infrastructure along the water, pipelines or otherwise, for additional oil production.

But the day before a key Sacramento committee hearing this summer, Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson (D-Santa Barbara) received some bad news about her legislation — it was opposed by a politically powerful labor group whose members’ paychecks depend on the steady flow of oil.

In a letter to lawmakers, the top lobbyist for the State Building and Construction Trades Council of California said he feared harming projects that “maintain and create new employment opportunities.” The legislation, Senate Bill 188, stalled the following day, an unceremonious defeat for a proposal announced with much fanfare months earlier.

“I was startled,” said Jackson, who represents a region with a painful history of oil spills but said she recognizes the jobs that fossil fuels provide. “I don’t think people say, ‘I love oil so much.’ It’s, ‘I have to feed my family.’”

The episode was a reminder of how an array of California unions, despite their vocal support for fighting climate change and their willingness to embrace green issues scorned by national labor groups, either bent or blocked environmental proposals during the legislative session that ended last week. At a time when the state is trying to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions, their effort to protect or create jobs threatens to conflict with goals to combat global warming.

Unions torpedoed an ambitious proposal to phase out fossil fuels for generating electricity after lawmakers refused to insert a provision limiting clean energy projects that don’t hire their workers. Another group pushed for changes that could stop the state from awarding electric car rebates to automakers involved in labor disputes.

Perhaps most notably, the building and construction trades reinforced oil industry opposition to an early version of cap-and-trade legislation shortly after they forged a new statewide labor agreement with Chevron, which operates two of California’s most productive refineries. The cap-and-trade program, which requires companies to buy permits to release greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere, was eventually extended by lawmakers in July, but on terms more favorable to oil companies.

Although the fossil fuel industry is the most obvious adversary of climate change policies, labor resistance can be an especially potent factor in a state dominated by Democrats who rely on political support from carpenters, electricians, pipe fitters and other blue-collar workers.

“I don’t think it’s a secret the influence they have,” said Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia (D-Bell Gardens), who authored the cap-and-trade legislation defeated with labor’s help.

The situation has frustrated environmentalists, another crucial Democratic constituency that often works with labor to advance green goals. The two factions have previously built alliances around landmark climate policies, such as a renewable energy mandate that protects union jobs with incentives for building new solar and wind plants in California. The building trades also support cap and trade because the sale of emission permits finances mass transit projects, including the bullet train from Los Angeles to San Francisco.

“We’re like cousins who occasionally go off in different directions, but sit down at Thanksgiving together,” said Kathryn Phillips, a Sierra Club lobbyist.

When schisms develop between environmentalists and unions, they reflect an anxiety over finding dependable jobs during a shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

“We believe that green energy is the way the world is going,” said Robbie Hunter, president of the state building trades council.

At the same time, he wants to protect the dwindling number of blue-collar jobs left in California, rattling off a list of industries — aerospace, steel, cars — that have fled the state over the years. Too many regulations have occasionally been a problem, Hunter said, and defending facilities such as oil refineries is “no different than a miner showing up trying to save his mine.”

The pressure to curtail fossil fuels has been a source of tension among progressives around the country. Last year, national trade unions harshly criticized an alliance with Tom Steyer, a billionaire donor and environmentalist from San Francisco, after he opposed building the Keystone XL pipeline, a project expected to create jobs.

Trump has directly appealed to that kind of divide, recently standing before a North Dakota oil refinery and promising to “unlock the extraordinary potential of our great American workers.”

“We’re getting rid of one job-killing regulation after another,” he said.

Kim Glas, executive director of the BlueGreen Alliance, a national partnership of unions and environmentalists, said pitting workers against the global warming fight represents a false choice. The goal, she said, is creating “an economy and a climate policy that’s more fair and equitable.”

In California, oil companies are also vying for labor’s loyalty and the clout that comes with it. During an industry conference in Kern County two years ago, a member of the audience asked a California Resources Corp. executive why the Los Angeles-based oil and gas company had signed a union agreement.

“We’re using the trades, mainly for their quality, and for the political power they bring with them,” said the executive, Robert Barnes.

This year the oil industry benefited from that political power when the building trades lobbied against Garcia’s Assembly Bill 378, which would have reshaped California’s cap-and-trade program to include more stringent regulations. A broad cross section of environmental advocates supported the proposal, but it fell short in the Assembly.

“Once labor came out against it, it killed my bill,” Garcia said.

The June vote came shortly after the building trades finished negotiating an expansive labor deal with Chevron. Initial drafts were exchanged two years ago and the agreement was finalized in May, ensuring 5 million hours of work annually for five years.

“It’s game-changing,” said Bill Whitney, who leads the building trades affiliate in Contra Costa County, home to Chevron’s Richmond refinery. “I don’t think there’s anything to come along like this in decades.”

There may not be a need for fossil fuels in the distant future, Whitney said, but until then there’s no reason to “eviscerate the goose that lays the golden egg” for middle-class workers.

Hunter said the statewide agreement with Chevron was the logical result of state law requiring refineries to hire more workers who graduate from apprenticeship programs, which “gives us a common cause” with the oil industry.

A spokesman for Chevron, Braden Reddall, said the agreement will “help further guarantee access to a qualified labor force” for the company’s refineries.

A breakdown of the cap and trade program.

The enduring value of oil jobs is a challenge for environmentalists.

“Some of these industries that are emissions intensive are also the industries where the worker protections are strongest and the wages and compensation has been the best,” said Betony Jones, director of the Green Economy Program at the UC Berkeley Labor Center.

Labor influence over climate policies occasionally made Democrats uncomfortable last week. One late addition to state budget legislation, Assembly Bill 134, directs regulators to develop a process for determining whether automakers are “fair and responsible” in their treatment of workers.

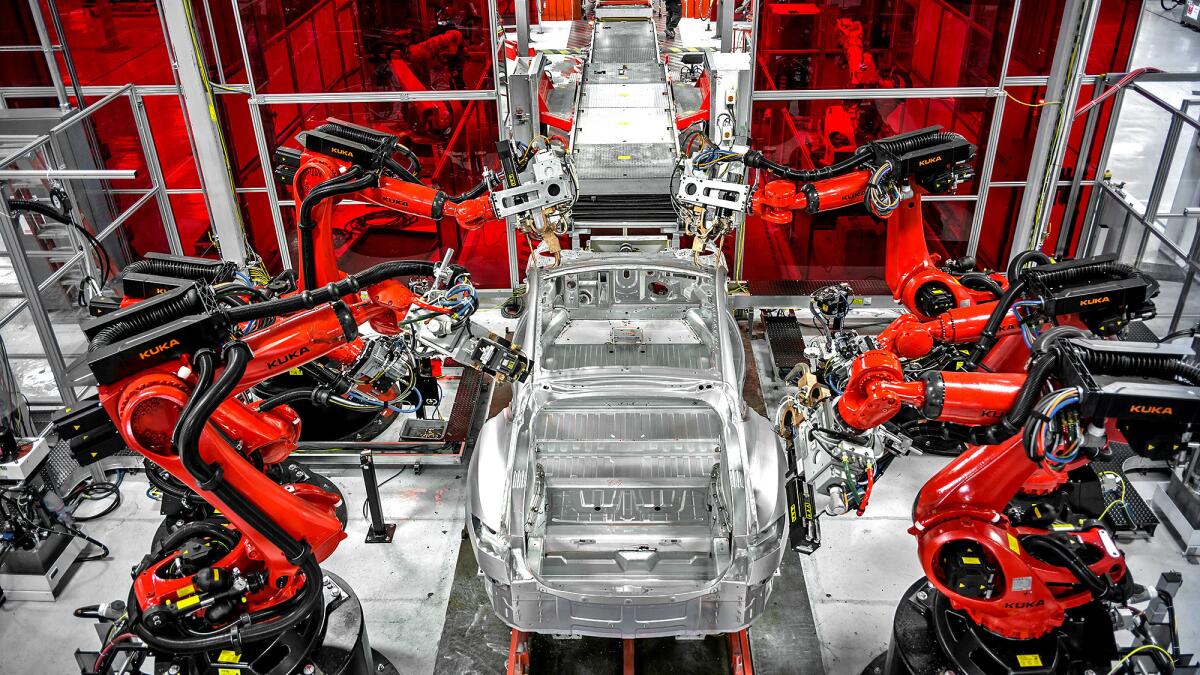

If lawmakers approve the process next year and companies fall short of that standard, their electric cars could become ineligible for California rebates that are crucial to making zero-emission vehicles more cost competitive. Tesla, the state’s only automaker, has resisted efforts to unionize the workforce at its Fremont factory.

The provision was supported by the California Labor Federation, a coalition that includes the United Auto Workers, as a way to ensure public money doesn’t flow to companies that mistreat employees. But these kinds of rules could end up “undermining our own goals” of fighting climate change with more electric cars, said Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco).

Another example of union influence came during the debate over Senate Bill 100, which would have required the state to stop using fossil fuels for generating electricity by 2045. The proposal was announced in May and appeared to be cruising through the Legislature until support within the labor community fractured.

Although the building trades, eager for jobs building new solar plants, remained supportive, unions representing electrical and utility workers announced their opposition the week before lawmakers adjourned for the year.

The unions wanted lawmakers’ help curbing the role of so-called distributed resources, such as rooftop solar panels and batteries for storing energy, that are owned and operated by private companies instead of utilities. Environmentalists view the initiatives as key tools for reducing emissions, but the unions called them a dangerous example of electricity grid deregulation that also threatens their jobs.

“We have a parochial self-interest in this,” said Tom Dalzell, business manager for the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 1245.

The legislation stalled in the Assembly, a defeat for the author, Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles). He plans to push the proposal next year and acknowledged more work will be needed to ensure environmentalists and unions are on the same page.

“It’s going to be really important in the immediate future that we bridge the gap between labor and clean energy,” he said.

Twitter: @chrismegerian

ALSO

California clean energy proposals face demise as opposition fails to yield

Updates on California politics

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.