Rubio enjoys a moment in the sun -- now the hard part starts

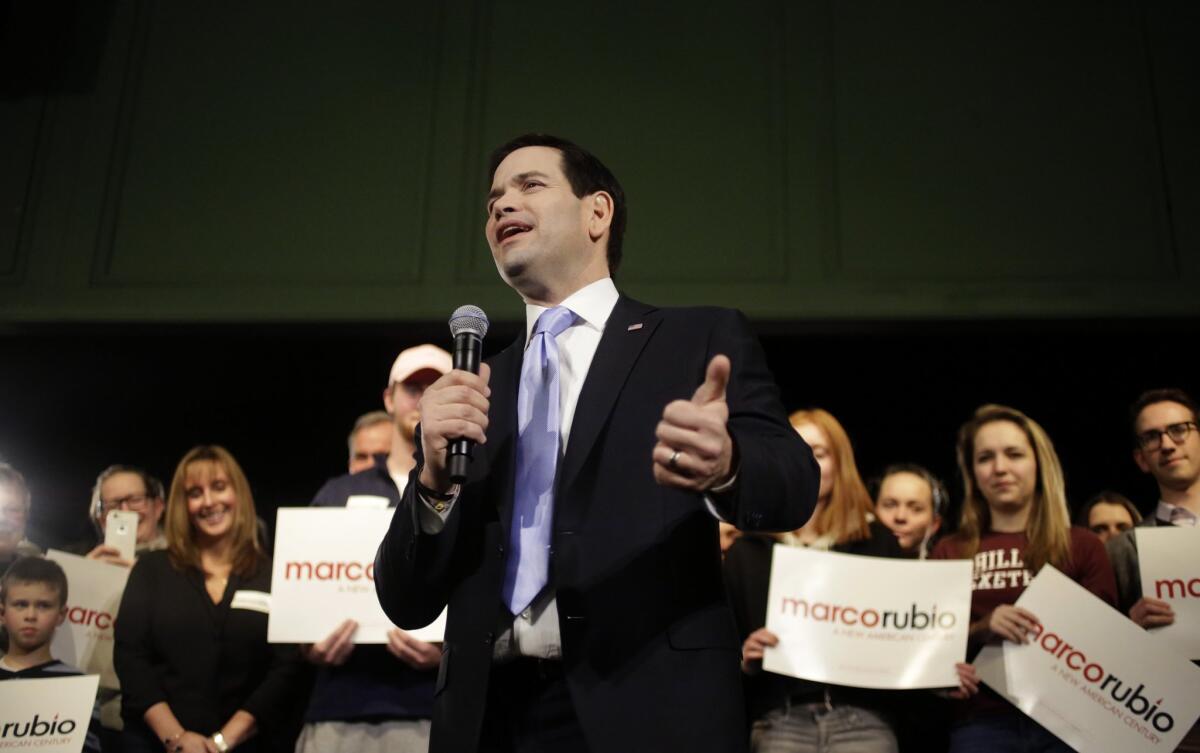

Marco Rubio campaigns in Exeter, N.H., on Tuesday, one day after finishing third in the Iowa caucuses.

Reporting from Exeter, N.H. — In the nine months in which he has run for president, Marco Rubio’s ambitions have been confounded by contradictions.

He is the self-styled candidate of the future many of whose policy prescriptions draw from the 1950s. He is the candidate of sunny aspirations in a race that has glowered with anger. He was the candidate who wanted immigration reform until he didn’t, angering all sides. He was too young, too impatient, too thirsty, too profligate with other people’s money — and then there were those much-mocked high-heeled boots.

And now? Marco Rubio is the presidential campaign’s newest sensation, the target of laser-like attention Tuesday after his surprising third-place finish in the Iowa caucuses, opening his New Hampshire campaign with the hope that Midwestern momentum will propel him past all those who doubted.

In the graceful old town hall in Exeter, he began his pitch to voters Tuesday night — one familiar to those who have followed him, but now being watched by a new, broader audience. It also is full of contradictions, harsh and apocalyptic warnings about the future of the country merging with lyrical optimism.

He blistered President Obama, Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, popular culture, Obamacare, fellow Republicans, efforts to impinge on the 2nd Amendment and circumstances that he said led to a country that “is slipping away.”

When he is elected, he said, “I am going to repeal every single one of Barack Obama’s unconstitutional executive orders. That means that all these crazy EPA rules that are destroying jobs in America — on my first day in office they’re gone. This executive order that undermines the 2nd Amendment; on my first day in office it’s gone.... On my first day in office any work to impose Common Core stops — on my first day in office.”

But he leavened the tough talk with a kind of personal appeal that few in the Republican field can emulate, repeating the evocative personal story of his bartender father and his mother, a maid. It served to connect his life experiences to voters for whom siding with a candidate named Rubio is an unusual leap.

“What makes America special is not that we have rich people … but what makes us special are the millions of people that know they’re never going to be rich, and that’s not what they want,” he said, lauding nurses and teachers and firefighters. “They want to be happy.”

Rubio’s words appeared to take hold; many of the 700 people on hand left bearing Rubio signs. But now the hard part begins.

Throughout the campaign, Rubio has pushed the notion that he is best equipped to take on the Democratic nominee in November, and voters in Iowa responded to that message. Of the 21% of voters in that state’s caucuses who said November was uppermost in their minds, Rubio won 44%.

Until Monday night, he had been caught in a tight quartet of single-digit candidates on the establishment side of the GOP spectrum, a group that included Ohio Gov. John Kasich, former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie. Rubio moved swiftly Tuesday to redirect the party’s establishment money to him alone.

“My opponents are going to try to ignore my showing in Iowa,” he wrote in a fundraising missive. “They will increase their relentless attacks in the hopes that we will not put up a fight and fade into the distance. And that could not be further from the truth.”

Indeed, Rubio has been under sustained assault in New Hampshire, particularly from the well-financed allies of Bush, who saw Rubio as the impediment to his own upward mobility.

Bush’s allies have asserted in ads on New Hampshire television that Rubio is “just not ready to be president.” Bush in a Monday night speech in Manchester called Rubio and Iowa winner Ted Cruz “backbenchers that have never done anything of consequence in their lives.” Both men are first-term senators, a circumstance that Bush and other candidates have argued is too reminiscent of Obama during his presidential quest.

Rubio has returned fire with an ad, opening with sepia-toned pictures of Clinton and Bush, calling them “two names from the past, tied to the past, with ideas from the past.”

“It’s time for a new generation of leadership,” Rubio said, words that were echoed in radio advertisements in New Hampshire.

His challenges are many. On the financial front, Rubio is competing with Donald Trump, who can finance the campaign out of his wallet if need be, and Cruz, who has amassed a broad donor base amid impressive early fundraising.

Rubio may benefit from a deep well of establishment conservatives in New Hampshire, although a substantial showing would require him to cut significantly into Trump’s double-digit lead here. After New Hampshire, the terrain gets even more complicated.

On Tuesday, he picked up the support of Republican Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina, which holds the first GOP contest after New Hampshire on Feb. 20. Scott reiterated the campaign’s theme: “We have one shot in 2016 to beat Hillary Clinton and that shot is Marco Rubio, and with him as our candidate, we win.” Yet Rubio faces stiff competition in a state known for hardball politics.

Matt Moore, chairman of the South Carolina GOP, said Cruz had been in the state often “and that matters.” Trump, he said, has been greeted with “gigantic crowds.”

The Palmetto State’s Republicans, he suggested, require some dexterity.

“You can’t be a one-trick pony in South Carolina,” Moore said. “You have to be liked by a broad spectrum in the state.”

Nevada, the fourth Republican contest, offers some hope for Rubio, given that he spent part of his childhood in Las Vegas. But he has lagged in polls there. After that come the Southern primaries, which are dominated by evangelical voters who have rallied to Cruz’s side this year and formed the base of his Iowa victory.

Part of the promise of Rubio’s candidacy is that as a young senator of Cuban descent, he can put a fresh face on the Republican Party and attract voters who may have been put off by the older, white, male candidates of the past. But Rubio’s policy views may stunt any such growth.

Key targets of an expansion of the Republican presidential base would include women, Latinos and Asian voters. But Rubio opposes abortion without exceptions and would defund Planned Parenthood, a position opposed by many women who are not conservative.

His immigration history — he first proposed and then objected to a plan that would allow a path to citizenship for those in the country illegally — is likely to lead Latinos and Asians to be skeptical. And he favors the immediate repeal of Obama’s healthcare plan, which is immensely popular among those groups.

His candidacy would be a test of image over policy, both during the Republican primaries and, if he is successful, in the general election.

In New Hampshire, however, he seemed to be carrying his Iowa momentum with him. Although some at the Exeter event grumbled that he took no questions in what was advertised as a town hall, he also drew some rave reviews. Two women walking out said they’d come to the event tossing over their options and left as Rubio voters.

“It’s like Kennedy versus Nixon,” one said of Rubio against the rest of the GOP field. “And he’s Kennedy. He has the vitality.”

Twitter: @cathleendecker

Twitter: @lisamascaro

Decker reported from Exeter and Mascaro from Washington.

ALSO:

Marco Rubio’s childhood in Las Vegas shaped his politics

A farm town’s debate over immigration yields surprises

Marco Rubio’s strategic gamble

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.