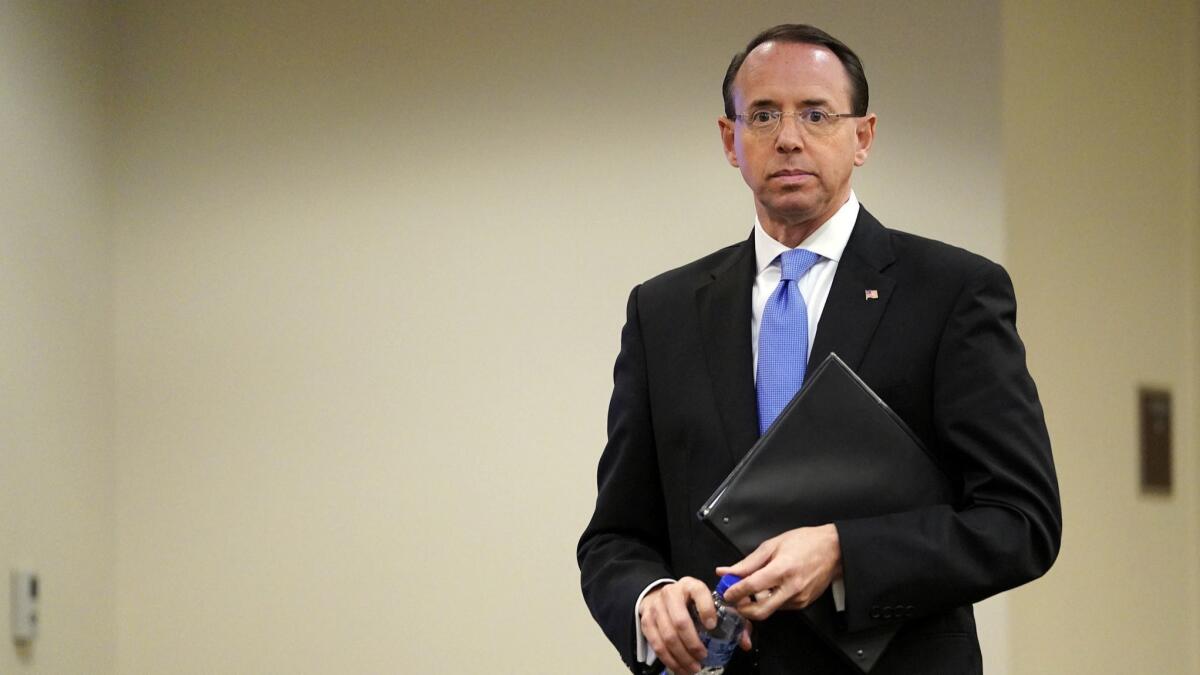

As Mueller report nears, Rod Rosenstein prepares to exit

Reporting from Washington — After President Trump picked Rod Rosenstein two years ago for the second-highest job at the Justice Department, his daughter asked if his picture would appear in the newspaper.

“I said, ‘No,’ ” Rosenstein later recalled. “I told her, ‘The deputy attorney general is a low-profile job. Nobody knows the deputy attorney general.’ ”

For the record:

9:15 a.m. Feb. 25, 2019An earlier version of this article said a photo hanging in Rosenstein’s office of his family and the president was taken at Rosenstein’s swearing-in. The photo was taken Jan. 2.

Instead, Rosenstein’s role overseeing the Russia investigation made him a household name, the target of political attacks and a key figure in a sprawling counterintelligence and criminal investigation that has ensnared some of Trump’s top former aides.

Now his tenure is coming to an end. The White House announced late Tuesday that Trump would nominate Jeffrey A. Rosen, the deputy secretary of Transportation, to replace Rosenstein as the day-to-day manager of a department with more than 100,000 employees and a $28-billion budget.

A taciturn former prosecutor, Rosenstein was thrust into the limelight when Trump fired FBI Director James B. Comey in May 2017. Jeff Sessions, then attorney general, had recused himself from supervising Comey’s investigation of alleged ties between the Trump presidential campaign and the Kremlin, leaving the job to his deputy.

Amid a public uproar after Comey’s ouster, Rosenstein appointed Robert S. Mueller III, a former FBI director, as special counsel to ensure a degree of independence from the White House. Mueller would report directly to him.

Since then, Mueller has filed criminal charges against 34 individuals, including 25 Russians and several of Trump’s former top advisors, including his campaign chairman, national security advisor and personal lawyer.

Mueller’s investigation is said to be wrapping up, and his report now will go to the new attorney general, William P. Barr, who was confirmed by the Senate and took office Thursday. Rosenstein had previously signaled that he would step down after Barr, whom he admires, takes over. He is expected to stay until mid-March.

In a statement, Barr said Rosen’s “years of outstanding legal and management experience make him an excellent choice to succeed ... Rosenstein, who has served the Department of Justice over many years with dedication and distinction.”

Rosenstein had a rocky relationship with Trump, however. He staunchly defended Mueller even as the president repeatedly denounced his investigation as a “witch hunt” and a “hoax,” and once tweeted a photograph depicting Rosenstein behind bars.

Despite the attacks, Rosenstein keeps a framed photo on his office wall of his family and the president in the Oval Office taken in January. Rosenstein declined requests for an interview.

Rosen spent nearly 30 years at Kirkland & Ellis LLP, an international law firm with powerful connections in the White House.

Its alumni include Barr, Supreme Court Associate Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, national security advisor John Bolton, Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar, Secretary of Labor Alexander Acosta and other senior administration officials.

Rosen joined the Trump administration as general counsel for the White House Office of Management and Budget, and later served as general counsel at the Department of Transportation. A graduate of Northwestern University and Harvard Law School, Rosen has not previously worked as a prosecutor.

The Senate confirmed Rosen as undersecretary of Transportation in May 2017 by a vote of 56 to 42. Only three Democrats, including the two senators from his home state of Virginia, supported his nomination.

Rosenstein is one of the rare high-ranking Trump administration officials to leave on his own terms, a distinction all the more notable for his often fractious relationship with the president.

He was also one of the few administration officials who was previously a political appointee in a Democratic administration. He served as U.S. attorney in Maryland under Presidents George W. Bush and Obama.

He was expected to resign or be fired last fall after news reports said he had discussed wearing a wire to secretly record his conversations with Trump, or trying to remove him from office via the 25th Amendment, in the tumultuous days after the president fired Comey.

The 25th Amendment allows the vice president and a majority of the Cabinet to start the process of ousting a president if they determine he is “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.”

Although Rosenstein angrily denied the reports, Andrew McCabe, who was fired last March as deputy FBI director, repeated the allegations in recent days as he was promoting a book about his career. That provoked furious new tweets from the president and Republican calls for Senate hearings.

In response, the Justice Department said Rosenstein “again rejects Mr. McCabe’s recitation of events as inaccurate and factually incorrect.”

It said that “based on his personal dealings with the president,” Rosenstein saw “no basis to invoke the 25th Amendment” and was not “in a position” to do so.

The president was not mollified. On Monday, he tweeted that Rosenstein and McCabe were “planning a very illegal act, and got caught.”

Rosenstein grew up outside Philadelphia and, after attending Harvard Law School and clerking for a federal appeals court judge, rose through the ranks at the Justice Department.

He worked on the independent counsel investigation of the Whitewater real estate investments by President Clinton and his wife, Hillary — neither was charged in the case — and became a federal prosecutor in Baltimore.

Rosenstein served as U.S. attorney in Maryland from 2005 until Trump, who praised his focus on violent crime, nominated him as deputy attorney general in January 2017. He was confirmed in the Senate with overwhelming bipartisan support.

In May 2017, Trump asked Rosenstein and Sessions to lay out a case for firing Comey, who was then heading the Russia investigation.

In a lengthy letter, Rosenstein sharply criticized Comey for his handling of the FBI investigation into Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server when she was secretary of State. The White House initially cited the letter to explain Trump’s decision.

But Trump later told a TV interviewer that he had previously decided to fire Comey because of what he called “this Russia thing,” raising questions about whether the president had sought to improperly shut down or influence a federal investigation. Trump warmly greeted two senior Russian diplomats in the Oval Office the day after he fired Comey, a meeting first disclosed by Russian-government media, not the White House.

Days later, Rosenstein appointed Mueller as special counsel and gave him broad authority to investigate whether Trump’s team conspired with Russians to influence the 2016 presidential election or committed other crimes. Prosecutors are also examining whether Trump obstructed justice.

The decision infuriated Trump because it ensured the investigation would continue to cast a cloud over the White House. Rosenstein also became the target of persistent attacks from congressional Republicans, who accused him of withholding documents they had subpoenaed to determine whether the inquiry was being properly run.

Although it has uncovered a raft of other crimes, the special counsel’s office has yet to file a case accusing Trump or his aides of conspiring with Moscow’s effort to steal and release Democratic Party emails and target U.S. voters with false information, the initial focus of the investigation.

Twitter: @chrismegerian

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.