Mueller report sets up legal clash over executive privilege and congressional oversight

Reporting from Washington — The Constitution does not directly say Congress has the power to conduct investigations or oversight of the executive branch. Nor does it say the president may invoke “executive privilege” to shield information from members of Congress.

But both powers — congressional oversight and executive privilege — have long been asserted and upheld by courts, with limits.

Each convinced the Constitution is on their side, House Democrats and President Trump are now testing the legal limits of those powers in a fight over the redacted parts of special counsel Robert S. Mueller III’s 448-page report as well as documents and investigative material created during the two-year investigation.

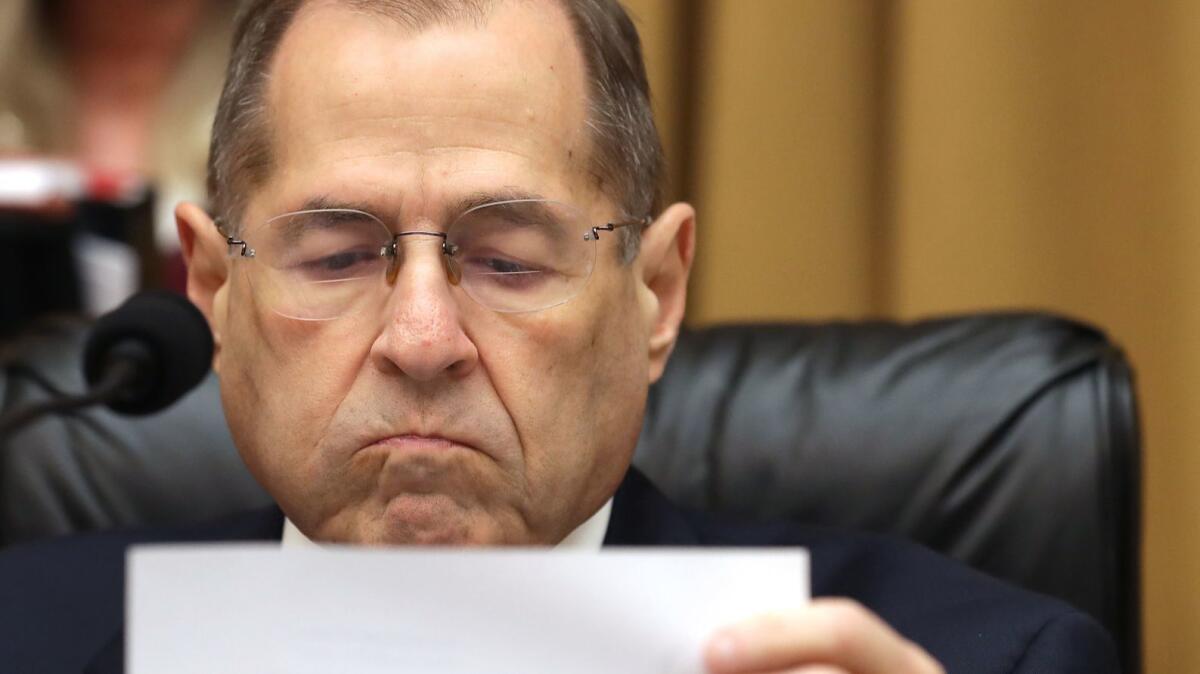

The House Judiciary Committee voted this week to hold Atty. Gen. William Barr in contempt for what Chairman Jerrold Nadler (D-N.Y.) called the “Trump administration’s blanket defiance of Congress’ constitutionally mandated duties. This is information we are legally entitled to receive, and we are constitutionally obligated to review,” he said.

A few hours before the vote Wednesday, the Justice Department said the president would invoke executive privilege to block the release of the unredacted report. In a letter to Nadler, Assistant Atty. Gen. Stephen Boyd argued that Barr’s aides said the Democrats were demanding “millions of pages of classified and unclassified documents,” including from a dozen pending cases. Prosecutors have a duty to keep secret information and interviews unless they result in an indictment, they said, and Congress has no legitimate role in “simply duplicating a criminal inquiry, which is, of course, a function that the Constitution entrusts exclusively to the executive branch.”

Both sides now seem willing to take the fight to court, but legal experts say that is not likely to result in a quick decision or a clear, resounding victory for either side. In the past, judges have been reluctant to decide disputes over documents between Congress and the executive branch, viewing them as essentially political — not legal — struggles.

Ever since the Supreme Court ruled in 1974 that President Nixon had to turn over secret tapes despite his claim of executive privilege, clashes between congressional oversight and executive privilege have usually been resolved by a compromise — without forcing judges to reach a final decision on where to draw the line.

But given today’s partisan rancor, a settlement may not be possible, leaving the courts to potentially strike a new balance.

“The reality is that no one really knows how this turns out or on what time frame,” said Margaret L. Taylor, a former Democratic counsel for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and a scholar at the Brookings Institution.

She said the law in this area is not clear, since courts have rarely acted as the referee in these highly political battles. “The case law addressing the scope of executive privilege is sparse. If this goes to court, it’s likely to be a messy and time-consuming path. My sense is that such an outcome would be perfectly OK from the president’s perspective. It seems he views it is in his favor politically to be seen as fighting the House Democrats,” she said.

Democrats could have the same motivation to be seen as defying Trump, particularly heading into the 2020 election.

In a timely reminder of how long such disputes can drag on, the Justice Department announced a settlement agreement late Wednesday, ending the 7-year-old dispute over Operation Fast and Furious, a bungled Obama-era gun-running investigation. House Republicans led by former Oversight Committee Chairman Darrell Issa were convinced top officials of the Obama administration had covered up their role, and repeatedly demanded more internal files. President Obama eventually invoked executive privilege, and then-Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr. was held in contempt by the Republican-controlled House.

Then, it was the Republicans in Congress asserting they had duty of oversight, and Democrats in the executive branch contending that some sensitive files should be withheld. Now that political control has switched--with Republicans in charge at the Justice Department and Democrats in control of the House. After years of fighting, both sides were glad to quit and walk away.

Lawyers say neither executive privilege nor congressional oversight is a winning principle if pushed too far.

“Executive privilege is personal to the president, and it’s not an absolute privilege. And it doesn’t work as a general claim of confidentiality,” said Paul Rosenzweig, a Washington lawyer who worked on independent counsel Kenneth W. Starr’s investigation of President Clinton.

In the most famous example, the Supreme Court in 1974 agreed Nixon had a “privilege of confidentiality” in his secret White House tapes. But they also said Nixon’s right was outweighed by the demands of a criminal investigation into the Watergate burglary and its cover-up.

The Watergate tapes case cut in two directions. On the one hand, it established that presidents have a privilege protected by the Constitution to keep some information secret. At the same time, it put limits on that power. Also, future presidents have been wary of invoking this privilege because of its association with Nixon’s cover-up.

Even so, most presidents since Nixon have invoked the privilege at one time or another.

Trump’s invoking of executive privilege now “strikes me as a bit of an overreach,” said Rosenzweig. “It may work as a tactic if the president wants to put off everything until after the election. It appears he thinks he can run on fighting the Democrats,” he said.

Rosenzweig also questioned the power of congressional investigators, particularly when probes are seen as highly partisan. “Congress is a weak player. They have systematically weakened themselves over time,” he said.

After Wednesday’s long debate, the Judiciary Committee voted as expected, with all the Democrats in favor of the contempt motion and all the Republicans opposed. By contrast, the House in the Watergate era was powerful and effective because Democrats and at least some Republicans agreed on the need to investigate Nixon.

In letters to Nadler, Boyd repeatedly said the Justice Department was open to a “reasonable accommodation” if the committee would point to specific areas where it needed to see the underlying interviews with witnesses. He invited Nadler and other congressional leaders to review the full Mueller report “with redactions only for grand-jury information because disclosure of that information is prohibited by law. That would permit you to review 98.5% of the report, including 99.9% of Volume II,” which dealt with obstruction of justice.

At the same time, Trump has rejected efforts to compromise or make accommodation. “We’re fighting all the subpoenas,” he said.

Nadler said the offer to see more — but not all — of the Mueller report is inadequate. “The administration has announced—loud and clear—that it does not recognize Congress as a co-equal branch with independent constitutional oversight,” he said Wednesday. In the last Congress, he said, the “department produced more than 880,000 pages of sensitive investigative material” involving Hillary Clinton.

“No person—and certainly not the top law enforcement officer in this country—can be permitted to flout the will of Congress and to defy a valid subpoena,” he said.

More stories from David G. Savage »

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.