Column: Trump’s plaintive but welcome message to Iran: Can we talk?

Reporting from Washington — You know we’re in trouble when President Trump looks like the adult in the White House.

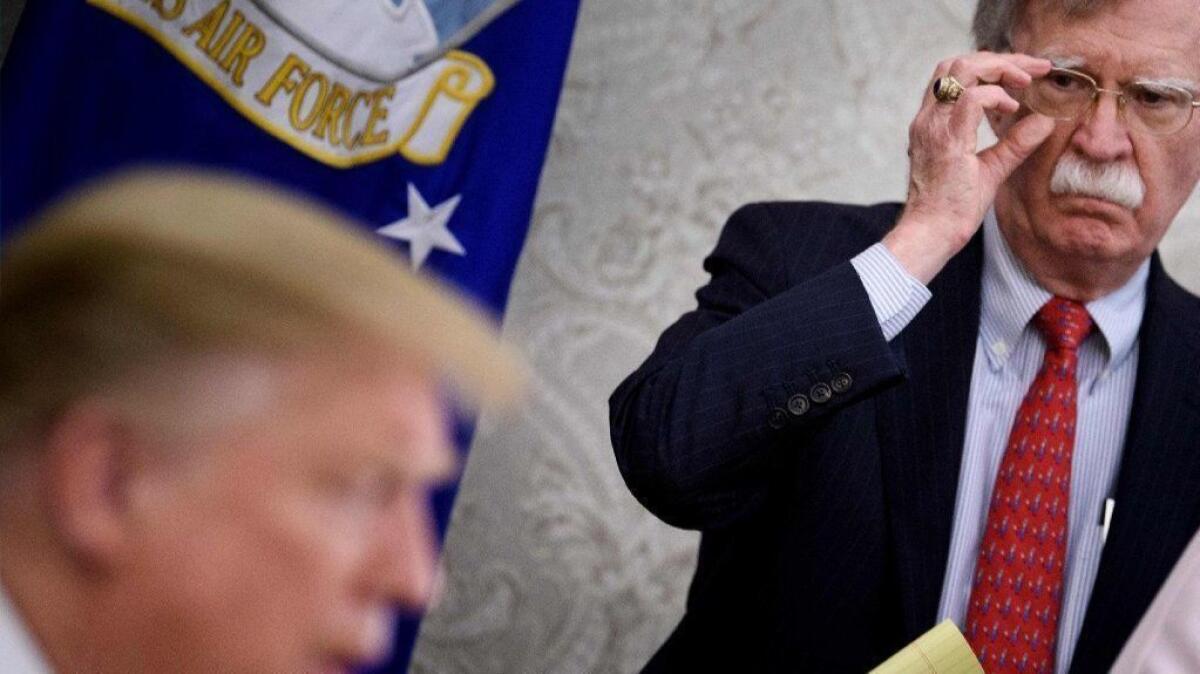

Starting on May 5, Trump’s hawkish national security advisor, John Bolton, dramatically escalated pressure on Iran — announcing the deployment of an aircraft carrier and B-52 bombers, ordering up contingency plans to send 120,000 troops, warning against allegedly threatening behavior.

Trump finally intervened, saying he’s not interested in launching a new war in the Middle East. He sent Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo to reassure allies that he wants negotiations, not airstrikes.

That shouldn’t be a surprise. Trump campaigned for the presidency on a promise to end America’s long, costly wars. He enjoys thumping his chest — remember when he warned North Korea of “fire and fury like the world has never seen” — but the bluster is intended to jump-start negotiations, a pursuit at which Trump believes he has no peer.

So it has been with Iran. After all the tough talk and menacing warships, Trump’s basic demand of the ayatollahs was almost plaintive: Can we talk?

“What they should be doing is calling me up,” the president said on May 9. “We can make a deal, a fair deal.”

The mini-crisis with Iran wasn’t the first time Bolton’s efforts to put the U.S. on a war footing has conflicted with Trump’s preference for deal-making. That difference has produced a remarkable string of public disagreements between the president and his chief national security advisor.

On North Korea, Bolton has argued that the United States will never persuade Kim Jong Un to give up nuclear weapons, and that Trump should consider military strikes instead. Trump disagrees, and even removed Bolton briefly from his negotiating team.

In Syria, after the Islamic State lost its self-declared caliphate, Bolton said U.S. troops would stay in the country until the last Iranian went home. Trump overruled him and ordered the troops out. (He later relented, but still insists the troop commitment will be brief.)

In Venezuela, Bolton was the administration’s leading champion of a U.S.-backed coup attempt against the autocratic regime of Nicolas Maduro. When the coup collapsed, Trump was furious, reportedly raging that Bolton had misled him about the chances of success.

In Iran, Bolton has long promoted regime change as his goal. Earlier this year, on the 40th anniversary of Iran’s revolution, he posted a taunting video message to the country’s leader: “I don’t think you’ll have many more anniversaries to enjoy.”

That’s not Trump’s message.

“We’re not looking to hurt Iran,” the president told reporters. “I want them to be strong and great.”

All those collisions raise a question: Why does Bolton still have his job?

After last week’s war scare, Washington’s gossip mill went into overdrive. Insiders traded stories of Trump’s annoyance with his national security advisor, especially over the perception that Bolton, not the president, was making key decisions.

Officials insist that Bolton’s job is not in serious danger. In past similar instances, when Trump has decided to fire an aide, he has aired his frustration on Twitter and floated the names of possible replacements.

That hasn’t happened to Bolton yet. Instead, Trump has joked about his advisor’s hawkishness, making it sound as if he enjoys playing the good cop to Bolton’s bad cop.

“I actually temper John, which is pretty amazing, isn’t it?” he told reporters. “I have John Bolton and I have other people that are a little more dovish than him. And ultimately I make the decision.”

In any case, Bolton isn’t the root of the problem between the United States and Iran. The two countries have clashed since Islamic revolutionaries overthrew the U.S.-backed shah in 1979, stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and held 52 Americans hostage for more than a year.

In the current round, the Trump administration accuses Iran of supporting militants in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen. Iran accuses the White House of trying to destroy its economy and topple its leadership. Both sides are essentially correct.

Trump raised tensions a year ago when he pulled out of the 2015 nuclear agreement and imposed stiff new economic sanctions, including a move to choke off Iran’s oil exports.

But on May 2, when the White House threatened to punish China, India and six other countries unless they cut their Iranian oil imports to zero, that got Tehran’s attention — and raised fears that Iran might seek to retaliate through terrorist attacks or Iranian-backed militant groups.

A week later, U.S. officials were alarmed by intelligence indicating that Iranian security forces had loaded short-range missiles onto vessels heading into the Persian Gulf. It was unclear whether Iran was preparing to strike an outside target or reacting defensively to what they saw as a growing U.S. threat.

The two countries were falling into a dangerous spiral: reading each other’s actions as aggressive, but seeing their own responses as defensive. That’s a situation that makes accidental or inadvertent escalation more likely.

For Trump, the solution is simple: direct negotiations with Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, much like the two summits he has held with North Korea’s Kim.

“I’m sure that Iran will want to talk soon,” the president tweeted Thursday.

So far, Iran’s supreme leader has refused to reopen the nuclear deal, the main issue Trump wants to discuss. His foreign minister, Mohammed Javad Zarif, says he has offered to engage in talks on other issues at a lower level, but the Americans haven’t replied.

So there are no direct channels of communication between Washington and Tehran, another factor that makes it easy for each side to misinterpret the other’s moves.

Trump likes to start crises as a way to force adversaries to talk. With Bolton’s help, he’s succeeded at the first step. Now can he find a way to take Step 2?

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.