Supreme Court appears set to overturn Mississippi murder case based on racial bias

Reporting from Washington — The Supreme Court justices sounded ready on Wednesday to overturn a Mississippi murder conviction because of racial bias in selecting jurors.

It marked the latest chapter in an extraordinary case involving a small-town white prosecutor who had repeatedly barred most or all black jurors from serving in six separate trials of Curtis Flowers, an African American defendant accused of killing four people.

From the opening moment of Wednesday’s argument, the Mississippi state attorney ran into sharp skepticism, not just from the court’s liberals, but from new Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh as well.

“We can’t take the history out of this case,” Kavanaugh said. The white prosecutor moved to strike 41 of 42 black prospective jurors, he noted. “How do you look at that and not come away thinking” that a blatant racial bias was at work, he asked.

The prosecutor, Doug Evans, had repeatedly used his allotted juror challenges to exclude black people. Three convictions were overturned by Mississippi’s high court because of misconduct or racial bias by the prosecutor. Two others led to mistrials after the juries deadlocked. In 2010, he won a murder conviction on all four counts — with a jury that had one African American and 11 whites.

The Supreme Court agreed to review the case of Flowers vs. Mississippi.

The argument featured a rare question from Justice Clarence Thomas. In his first question in open court since 2016, Thomas — who in the past has been skeptical of cases seeking to show racial bias in jury selection — asked whether the defense attorney in the Flowers trial had also excluded jurors, and what the race was of those potential jurors.

The history of racism in Mississippi loomed over the argument, and the only question for the justices seemed to be whether to focus narrowly on the jury in the last trial or more broadly on the pattern of racial discrimination that played out over all six.

In July 1996, four employees of a furniture store were found shot to death in Winona, Miss. Evans charged Flowers with the killings in part because he had been fired from the store a few days before.

The case made legal history in Mississippi. Not only has it resulted in six separate jury trials, but the saga was also the focus of a well-regarded podcast, “In the Dark,” that raised questions about the evidence against Flowers.

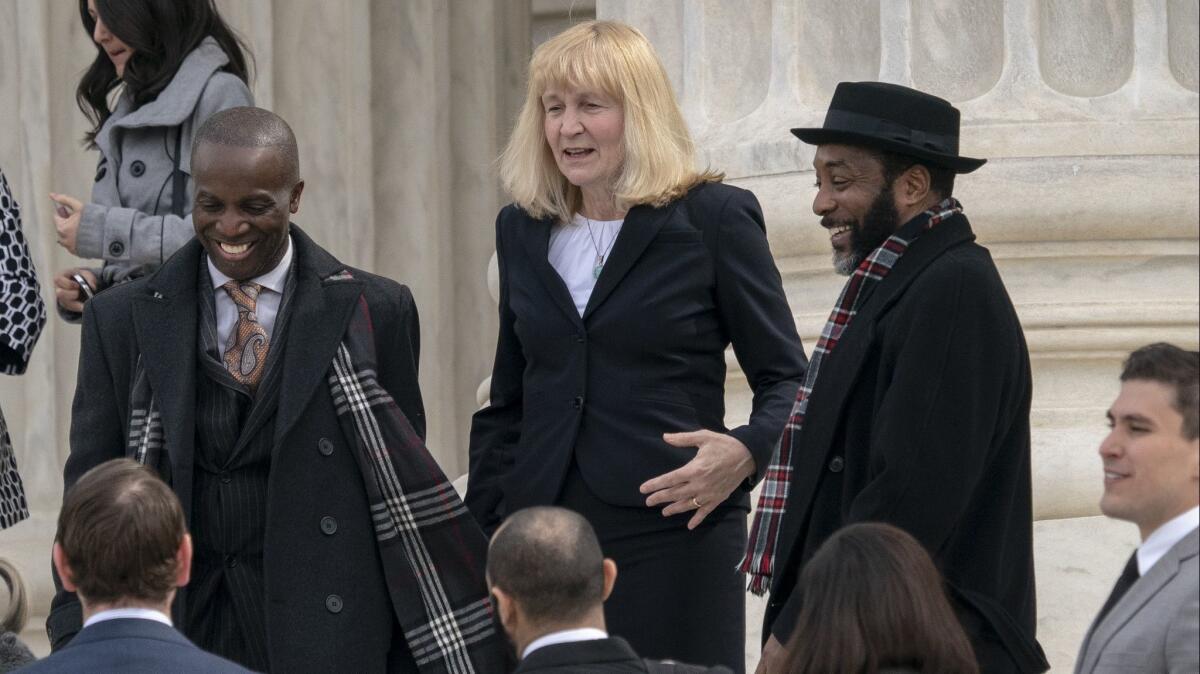

Cornell law professor Sheri Lynn Johnson, who represented Flowers, urged the justices to set aside the conviction yet again because the prosecutor has shown he will not abide by the law when it comes to selecting a jury.

“The history is relevant,” she said. It is “a history of a desire for an all-white jury, a history of willingness to violate the Constitution, and a history of willingness to make false statements to a trial court.” She argued that even if the justices focus just on the sixth trial, they should be highly skeptical of the prosecutor’s reasons for excluding black prospective jurors.

Under the 1986 decision in Batson vs. Kentucky, prosecutors are required to explain why they sought to strike a black person from a jury if there appears to a pattern of racial bias.

When selecting juries, Evans had peppered potential black jurors with numerous questions in an effort to find a nonracial reason to exclude them, Johnson said, but accepted potential white jurors after asking only a question or two.

Justice Elena Kagan agreed with the defense lawyer, citing as an example Carolyn Wright, a black woman who was struck from the jury in Flowers’ sixth trial.

“Ms. Wright is a perfect juror for a prosecutor, right?” Kagan told the state’s attorney, Jason Davis. “She strongly favors the death penalty. Her uncle is a prison security guard. Her relative is the victim of a violent crime. Except for her race, you would think that this is a juror that a prosecutor would love when she walks in the door.” But Evans excluded her nonetheless and explained that she may have owed money to the furniture store at one time.

For the high court, it is the latest of many efforts to remove race as a controlling factor in choosing jurors.

“Part of Batson was about confidence of the community and the fairness of the criminal justice system,” Kavanaugh said. “That was against a backdrop of a lot of decades of all-white juries convicting black defendants …. Can you say you have confidence in how this all transpired in this case?”

“I have confidence in this record,” the state’s attorney replied.

The justices did not sound convinced. Several asked why Mississippi’s attorney general had not stepped in and appointed a new prosecutor to try the case against Flowers. Davis agreed that idea sounded good, but he explained the state may intervene only if the local prosecutor asks for a change.

State officials may still get a chance to take over the case. If the Supreme Court overturns the conviction because of misconduct by the prosecutor, the case will go back to the state to decide whether to prosecute Flowers for a seventh time.

More stories from David G. Savage »

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.