Special Report: How do Americans view poverty? Many blue-collar whites, key to Trump, criticize poor people as lazy

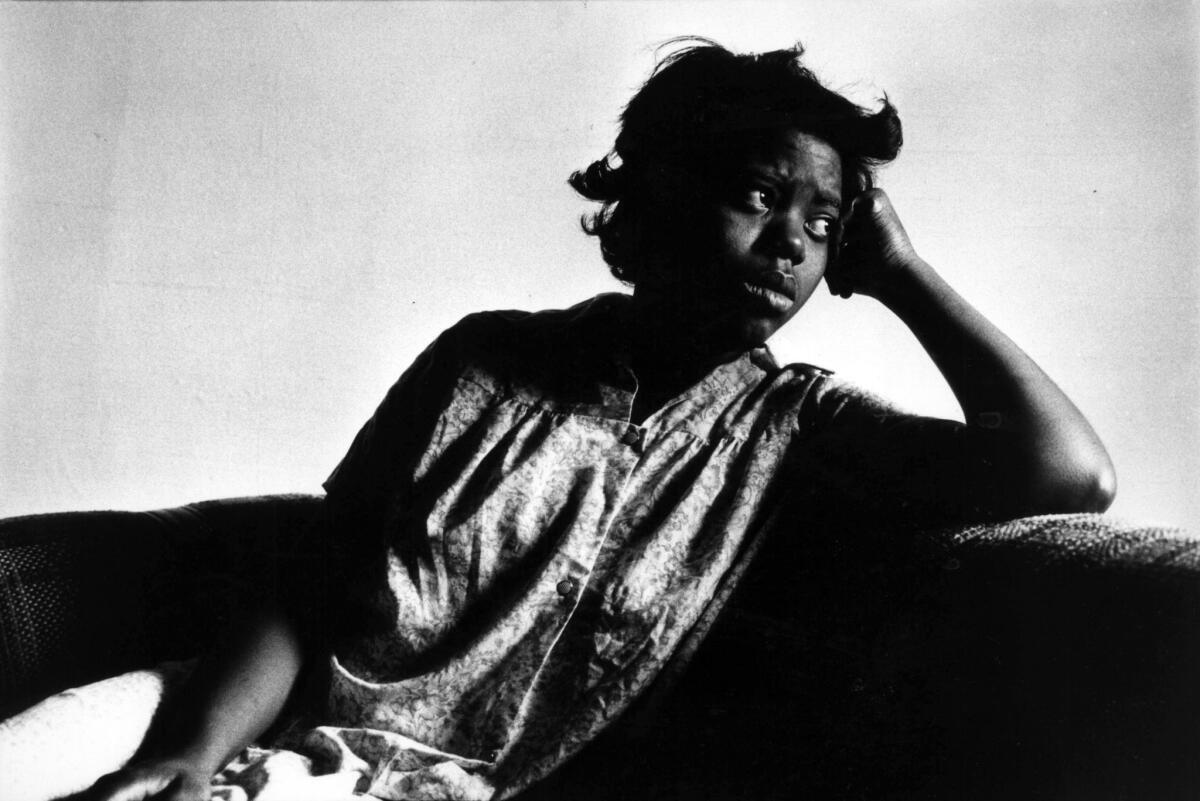

In 1985, Dorean Sewell talked to The Times about raising three children in a Baltimore low-income on her salary from a fast-food restaurant, as part of a newspaper series on American attitudes about poverty. A new poll by The Times and the American Enterprise Institute revisits those opinions.

Reporting from WASHINGTON — Sharp differences along lines of race and politics shape American attitudes toward the poor and poverty, according to a new survey of public opinion, which finds empathy toward the poor and deep skepticism about government antipoverty efforts.

The differences illuminate some of the passions that have driven this year’s contentious presidential campaign.

But the poll, which updates a survey The Times conducted three decades ago, also illustrates how attitudes about poverty have remained largely consistent over time despite dramatic economic and social change.

Criticism of the poor — a belief that there are “plenty of jobs available for poor people,” that government programs breed dependency and that most poor people would “prefer to stay on welfare” — is especially common among the blue-collar, white Americans who have given the strongest support to Donald Trump.

The opposite view — that jobs for the poor are hard to find, that government programs help people get back on their feet and that most of the poor would rather earn their own way — is most widely held among blacks and other minorities, who have provided the strongest backing to Hillary Clinton.

Roughly a third of self-described conservatives say that the poor do not work very hard, a view at odds with big majorities of moderates and liberals.

But while Americans disagree in how they view the poor, they’re more united in their skepticism of government programs.

That skepticism has held true for decades. The first Times poll of American attitudes toward poverty, in 1985, broke ground by surveying enough poor people to compare their views with those of people in the middle class.

The new survey, which was conducted by The Times and the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington think tank that is generally conservative, asked similar questions but with some updating.

Much has changed since the 1980s. Welfare got a major overhaul in the 1990s. The number of poor Americans dropped sharply in that decade, only to partially rise again, particularly during the deep recession that began in 2007.

But many attitudes have held steady, the new poll found, particularly doubts about the federal government’s ability to run its antipoverty programs, as well as their justification.

Most Americans do not believe that the government bears the main burden of taking care of the poor. Asked who has the “greatest responsibility for helping the poor,” just over one-third said that the government does. That figure has not budged in three decades.

Those who did not think the government has the main responsibility were split about who does. Just under 1 in 5 Americans said that the poor themselves bear the greatest responsibility. Family, churches and charities each got mentioned by 10%-15%.

Among Latinos, family came in second behind government; among blacks, churches took second place; Republicans were most likely to put responsibility on the poor themselves.

White Americans were less likely to call government responsible than were minorities, but the difference lay almost entirely with blue-collar whites — those without college degrees. White Americans who graduated from college were as likely to say government has the prime responsibility as were nonwhites.

Attitudes toward antipoverty programs also have not changed much since the 1980s.

In the original poll, 58% of Americans said that such efforts had “seldom” worked, while 32% said they “often” had. In the new survey, with a differently worded question, 13% of Americans said such programs have had “no impact” on reducing poverty, and 43% said they have had “some impact.” Only 5% said they have had a “big impact.”

Those living below the poverty line and those above it had largely similar views on that issue both now and three decades ago.

College-educated minorities were most likely in the current poll to say that government programs have had a positive impact on poverty, with more than 7 in 10 taking that view.

At the other end of the scale, about one-third of Americans said that government programs had made poverty worse, a view that was particularly common among conservatives, 47%, and blue-collar whites, 43%.

In both surveys, about 7 in 10 Americans said that even if the government were “willing to spend whatever is necessary to eliminate poverty,” officials do not know enough to accomplish that goal.

Blacks and Latinos were somewhat more likely to express confidence about the government’s ability to end poverty. Even among those groups, however — and among self-described liberals — majorities said the government does not know enough to eradicate poverty.

Asked why antipoverty efforts have failed, more than half of Americans said the main problem was that programs were poorly designed. Among poor people, however, about 3 in 10 said the problem was that programs had not been given enough money to succeed.

On attitudes toward the poor, divides are sharper than on opinions about government.

Blue-collar whites were much more likely than nonwhites to view the poor as a class set apart from the rest of society — trapped in poverty as a more or less permanent condition. Minority Americans, particularly blacks, tended to say that “for most poor people, poverty is a temporary condition”

A majority of whites see government antipoverty efforts contributing to poverty’s permanence, saying that benefit programs “make poor people dependent and encourage them to stay poor.”

African Americans disagreed, saying that the government help mostly allows poor people to “stand on their own two feet and get started again.” The poor themselves divided evenly on the question. Latinos leaned closer to the skeptical view about government programs expressed by white Americans.

Asked whether poor people “prefer to stay on welfare” or would “rather earn their own living,” Americans by a large majority, 61%-36%, said they believed the poor would rather earn their own way. Blue-collar whites were more closely divided on the question, 52%-44%.

That was one of several questions on which the views of minorities and college-educated whites were close to each other, while whites without a college degree stood out as different.

Nearly two-thirds of whites without college degrees, for example, said that benefits encourage poor people to remain in poverty. Among college-educated whites, about half took that view.

Blue-collar whites also took a dimmer view of President Obama’s handling of poverty than did other Americans. Majorities of blacks, Latinos and other minorities, as well as whites with college degrees, approved of Obama’s handling of poverty. But among blue-collar whites, fewer than one-third approved, and nearly two-thirds disapproved.

Not only are Americans skeptical about whether antipoverty programs work, nearly 6 in 10 said that the percentage of people in poverty has been increasing from year to year. About 1 in 4 say poverty has stayed the same, and and 1 in 8 say it has gone down.

Whether the public view of poverty getting worse is accurate or not is a tough question. A lot depends on the time frame.

Measured by the government’s official poverty line, the percentage of Americans who were poor declined during the 1960s, plateaued during the 1970s, rose during much of the 1980s, then declined again during the boom years of the 1990s, only to rise again since 2000, especially during the recession. In the last few years, the poverty rate has leveled off at about 15%.

The official poverty measure, however, does not include the value of government benefits designed to help the poor. Including those payments, the share of people who are impoverished is now considerably lower than it was in the 1960s, although slightly higher than it was at the end of the 1990s.

One question on which views have changed somewhat since the 1980s is whether poverty is a temporary or a permanent condition.

In the 1985 survey, Americans by a very large majority, 71%-21%, said that most poor people would probably remain poor. Today, that remains the majority view, but the gap has narrowed somewhat, with 60% seeing poverty as mostly permanent and 33% saying it is a temporary condition that people can move into and out of again.

The poor divide closely on that question. So do minorities.

A correct answer to that question is complex. Census figures show that in recent years, people who fell below the poverty line typically stayed poor for about six months. A lot of people, however, cycle in and out of poverty, rising only slightly above the official poverty line, then falling back.

One recent census study found that about one-quarter of poor people were in poverty only briefly — the result of a job loss or other crisis. About 1 in 7 were chronically poor, spending much of their lives impoverished. In between are many who churn in and out of poverty.

Across the board, Americans overestimate how high the government’s poverty line is and how many people live below it. Asked to estimate the poverty line for a family of four, those polled, on average, put it at just over $32,000, which is about a third higher than the actual figure of just over $24,000. The public’s figure may be more realistic, however; many poverty experts think the official level is far too low.

Those polled also estimated that about 40% of Americans live below the poverty line — far more than the actual figure of 15%. Again, though, the public may have the clearer view. Many experts on poverty say that in addition to the roughly 45 million Americans who live below the official poverty line, roughly an equal number are “near poor.”

Many federal benefit programs, including healthcare subsidies, food stamps and Medicaid in many states, are open to people earning significantly more than the official poverty threshold.

The survey was conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates, one of the country’s largest nonpartisan polling organizations. The survey was conducted June 20-July 7 among 1,202 adults aged 18 and older, including 235 who live below the poverty line. The survey has a margin of error of 4 percentage points in either direction for the full sample.

For more on politics and policy, follow me @DavidLauter.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.