A pipeline cutting through the iconic Appalachian Trail sparks a fight over natural gas expansion

The stretch of Appalachian Trail through the Blue Ridge Mountains here is prized by hikers from around the world for its open ridgelines, spectacular geologic formations and challenging slopes.

But one of the country’s most iconic viewsheds could soon be changed forever to make room for an energy project favored not just by fossil fuel industry boosters like

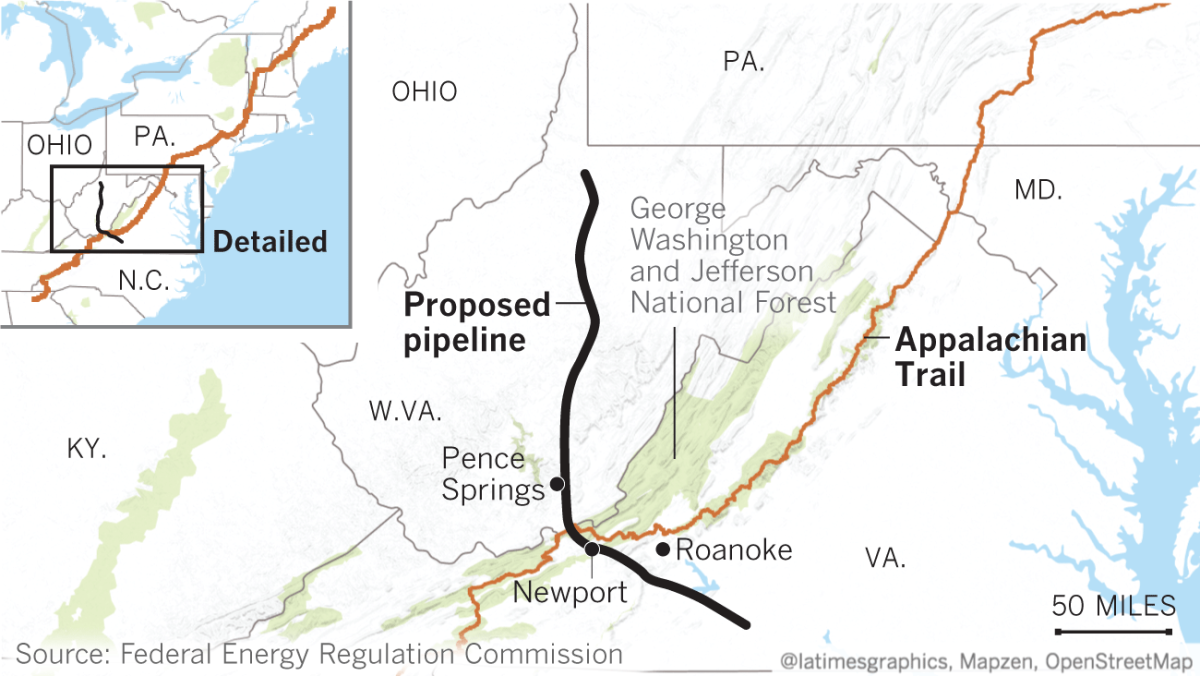

A natural gas developer with some powerful political allies is nearing final approval to plow a pipeline corridor as wide as 150 feet, tracking the trail for dozens of miles and burrowing through it at one point.

Amid the nation’s ongoing boom in natural gas production, federal rules have made pipeline construction an extremely lucrative enterprise, even in markets where the need is hotly debated.

To many, the Mountain Valley Pipeline has become a symbol of the building frenzy. Concern stretches all the way to California, where climate activists worry that such projects are undermining their efforts. Leaders of the Pacific Crest Trail Assn. fear that gas companies feel increasingly emboldened to impose an ever bigger footprint on protected lands.

“Everybody, not only in the East, but around every national scenic trail, should be concerned about this,” said Andrew Downs, regional director with the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, the 90-year-old nonprofit organization entrusted by the National Park Service decades ago with the task of managing the trail. The conservancy has never found it necessary to get involved in a pipeline fight in this way, but times have changed. “We’ve never seen pipelines of this size and magnitude,” Downs said.

The conservancy is joined by preservationists deeply concerned that the pipeline route would cut through seven historic districts. Those include the picture-postcard village of Newport, a place where generations of families have picnicked by the 100-year-old covered bridge and gathered at the 164-year-old church in the center of town. The pipeline has pushed Newport onto the list of “most endangered historic places” compiled by the group Preservation Virginia.

The same glut of natural gas that helped the U.S. substantially cut its greenhouse gas emissions is now also threatening efforts to fight climate change. In communities being rattled by the rush to lay pipe, the natural gas projects are drawing the kind of rancor usually associated with more imposing and disruptive oil pipelines.

With some 9,000 new miles of pipeline in the planning stages nationwide, natural gas expansions are threatening to undermine greenhouse gas emission reduction goals already agreed to by Virginia and other states hosting the projects.

“Gas helped this country get off coal, but now deep decarbonization requires getting off gas,” said Michael Wara, an energy law scholar at Stanford University. “If we build all this gas capacity, we will have a strong incentive to use it for its useful life, which extends well into 21st century. That will blow our climate goals.”

The benefit the Mountain Valley Pipeline would bring to those living along its 303-mile route is a point of intense disagreement and opinion does not cut neatly along partisan lines. There are local

“With the reserves we have right now on the East Coast, we are able to bring that energy to homes and business at reduced rates,” said Natalie Cox, a pipeline spokeswoman. “The availability of natural gas typically attracts manufacturing facilities. It is good for businesses.” Company officials said advocates were exaggerating the negative impacts on the Appalachian Trail.

Critics, including several national environmental organizations, say the benefits won’t be reaped by residents along the route, but by investors angling for a windfall. Those investors are permitted to collect an impressive 15% return on the project under federal rules left over from a time when domestic gas was not so plentiful and policies were designed to aggressively promote its discovery.

“The regulators are not looking carefully at which of these projects are appropriate and which are not,” said Thomas Hadwin, an area opponent of the pipeline and former utility executive with deep experience in permitting multibillion-dollar energy projects.

Pipelines are getting way overbuilt. We have a glut of them.

— Thomas Hadwin, Mountain Valley Pipeline opponent and former utility executive

It is not just pipeline opponents raising red flags. The Environmental Protection Agency in the final days of the Obama administration pushed federal energy regulators to more thoroughly investigate whether such projects are needed. It warned during the environmental review of the Mountain Valley Pipeline that the group building it had failed to explain why the project as proposed was essential, raising “the possibility of overbuilding, unnecessary disruption of the environment and unneeded exercise of eminent domain.”

Soon after, Norman Bay, the outgoing chief of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which oversees pipeline permitting, surprised the gas industry and activists by cautioning that the federal approval process for gas pipelines was full of shortcomings, creating a risk of overbuilding. In a six-page essay filed as part of a commission proceeding, Bay, long an ally of the industry, opined that regulators are not paying enough attention to legitimate concerns about the long-term viability of the projects, their impact on global warming and the hardships they can cause for communities along their routes.

The White House is hardly embracing such warnings. President Trump is vowing to step up the nation’s natural gas production, and he is working with the gas industry to substantially boost exports of American gas abroad, an issue he emphasized on his recent trip to Europe for the G-20 summit. Environmental groups suspect that much of the gas shipped through the Mountain Valley Pipeline will ultimately end up abroad, despite assurances from the developer and the Federal Energy RegulatoryCommission that the project is not designed for that.

The boom in gas pipeline construction was helped along in large part by the Obama administration, as it pursued an “all of the above” energy strategy. But Obama’s action on climate change in his final years in office sought to slow things down. The Clean Power Plan, Obama’s signature policy for addressing global warming, placed limits on the amount of natural gas that energy-producing states could use to meet federal emissions targets while transitioning from coal. The administration’s hope was to deter states from locking themselves into generations of reliance on gas, and instead prod them to leave room for a more robust expansion of renewable energy as its cost drops.

In March, Trump ordered the dismantling of the Clean Power Plan. But while the prevailing sentiment from Washington now more heavily favors pipeline investors, gas companies are finding their projects increasingly a tougher sell in the rest of the country. The local disruption the Mountain Valley Pipeline threatens along its route in Virginia and West Virginia has touched off an intense backlash.

Carolyn Reilly wasn’t an activist when she moved to the Blue Ridge Mountains four years ago. She was a home-schooling mom from suburban Florida, lured there by a bucolic patch of land and visions of launching a sustainable farming business. Now she finds herself rallying her neighbors to fight and calling the police every time pipeline surveyors try to access her property.

The easement the Mountain Valley Pipeline is seeking on Four Corners Farm, her family’s business in the hills outside Roanoke, cuts right through a peaceful pasture where a handful of cows were recently meandering. If given final approval, the pipeline company could use eminent domain to get it, and then set about tearing a pathway as wide as 150 feet with heavy machinery so that a 3½-foot diameter gas line could be buried underneath. Reilly worries about grazing patterns being disrupted, pesticides used to control vegetation on the corridor drifting into her crops and the property’s pristine water getting contaminated. “We believe this pipeline would destroy our business,” she said.

Some 130 miles away on a recent night, a group of West Virginians along the pipeline route gathered beside the Greenbrier River to build a large bonfire, fueled by copies of the pipeline construction application. “What they say in this is totally not true,” said longtime local resident Ashby Berkley, pointing to the charred documents.

Pipeline promoters say such grumbling is the exception and that they enjoy the support of a quiet majority in the area. They point to strong support from business leaders and chambers of commerce, as well as a poll they commissioned showing that 62% of Virginians support the project. Activists say the poll is bunk because poll-takers told those surveyed that the project was needed to meet the region’s energy needs. Three-quarters of landowners in the path of the pipeline have signed easement agreements, according to the pipeline company.

For now the project is in a holding pattern because the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission lacks enough sitting members to approve it. Trump’s nominees to fill those commission seats are awaiting congressional approval.

Meanwhile, opponents are preparing lawsuits and lobbying Congress.

“They thought we were just a bunch of hillbillies that they could roll right over,” said Diana Christopulos, president of the Roanoke chapter of the Appalachian Trail Club, as she walked along the trail recently. “They were wrong.”

Main photo: Danny Moody, 22, of Maine is hiking the entire Appalachian Trail with his dog Daisy. The view from the trail from the Mountain Lake Wilderness in Virginia will be changed forever if the Mountain Valley Pipeline project is approved.

ALSO

Winter's snow is disrupting this Sierra Nevada summer

Man confesses to killing 4 young men who went missing in Pennsylvania

In rebuke to Trump, federal judge in Hawaii expands travel ban exemptions

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.