Tens of thousands died due to an opioid addiction last year. With an Obamacare repeal, some fear the number will rise

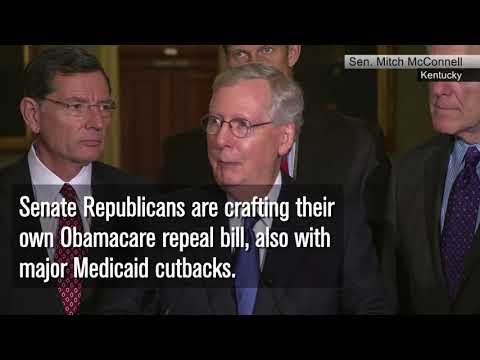

Senate Republicans are crafting their own Obamacare repeal bill, also with major Medicaid cutbacks. (June 21, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

Reporting from Cincinnati — There weren’t always strollers jamming the lobby of First Step Home, one of this city’s growing number of drug treatment centers.

But as the opioid epidemic has swept through Ohio, mothers with babies and small children have flocked to an aging block of brick homes just outside downtown Cincinnati. “It’s been breathtaking,” said Margo Spence, president of First Step Home, which nearly tripled the number of mothers it treats since 2013.

Now the future of this care is in doubt as Congress moves to roll back the Affordable Care Act and slim down or terminate health coverage for millions of Americans.

“I would 100% be on the street or dead without the health insurance,” said Stephanie Neeley, a 33-year-old mother who has Medicaid coverage through the healthcare law. Neeley came to First Step Home in March with her 2-year-old daughter seeking help for a decade-long addiction to pain medications and heroin.

President Trump and Republican congressional leaders insist their push to repeal and replace Obamacare won’t pull the rug out from Americans who rely on the law for vital health protections.

And the president has repeatedly pledged to bolster federal efforts to tackle the opioid crisis, promising during an address to a joint session of Congress in March that “we will expand treatment for those who have become so badly addicted.”

But along the front lines of the drug epidemic, there is growing fear that the rush to scrap Obamacare could deepen a crisis that last year claimed more than 50,000 lives. The GOP campaign to repeal the current healthcare law and deeply cut Medicaid would devastate efforts to help tens of thousands of patients in need of treatment, say many of those whose job it is to combat the epidemic.

“It would essentially write off a generation,” said Dr. Shawn Ryan, president of BrightView Health, a network of drug treatment clinics in Cincinnati. “It would be catastrophic.”

Underscoring the urgency of the crisis, a report from the federal government released Tuesday showed that opioid-related visits to hospital emergency departments nearly doubled between 2005 and 2014.

Medicaid’s role in the opioid crisis has become one of the most fraught issues in the current healthcare debate, as many states most affected by the epidemic, including Ohio, have Republican senators whose votes will be key to the repeal effort.

Repeal legislation passed by the House in April would slash more than $800 billion in federal aid to state Medicaid programs that insure low-income Americans, many with substance abuse issues.

And the White House is seeking even deeper reductions, calling in the next budget for an additional $600 billion in Medicaid cuts over the next decade.

Senate Republicans, who are currently crafting their own Obamacare repeal bill, are also discussing major Medicaid cutbacks, though they may implement the cuts more slowly.

Medicaid, which now insures some 70 million low-income Americans, historically covered primarily poor children, pregnant mothers and the low-income elderly.

But in recent years, the safety-net program has emerged as one of the most important tools in the opioid crisis, as Obamacare funding allowed states to open Medicaid to poor, working-age adults, a population traditionally not eligible for coverage.

In Ohio, more than a third of the approximately 700,000 people who enrolled in Medicaid after the expansion began in 2014 reported some drug or alcohol dependence, according to a recent study by the state.

The vast majority did not previously have health insurance.

That meant that Ohio, like most states, for years had to rely on a patchwork system of treatment programs funded by a mix of government grants, private donations and charitable efforts.

The system was poorly coordinated, funding was unpredictable and patients were often left on waiting lists to get methadone, buprenorphine and other medication-assisted treatments recommended for patients seeking to end their dependence on heroin or prescription painkillers.

Medication alone typically costs at least $300 a month. A year of treatment, including medications, medical appointments and counseling, can cost tens of thousands of dollars or more.

Such high costs once discouraged many patients from even seeking care.

Neeley was so desperate when she called First Step Home three months ago that she was stealing from local stores to pay her bills and finance her addiction.

Her drug dependence began a decade earlier while she was studying healthcare administration in Chicago. Diagnosed with lupus, a painful immune disorder, Neeley was prescribed pain medications.

Within a few years, she was seeking pills on the street. She then switched to heroin, which is often cheaper and more readily available than prescription drugs.

Neeley would ultimately lose custody of her two oldest daughters. Six months ago, her husband, an electrical engineer whom she met after the two children were gone, died of a drug overdose.

This spring, as she stood in a Wal-Mart parking lot with her youngest daughter, preparing to steal again, Neeley decided she had to stop. “I thought, ‘I’m going to end up dead or in prison, and my daughter will get sent to foster care,’ ” she recalled. “I had already lost two kids. I knew losing a third would break me.”

She took out her phone and searched the Internet for treatment centers that accepted children. First Step Home popped up.

Because Neeley qualified for Medicaid through Ohio’s Obamacare expansion, her inpatient treatment at the center is fully covered, as is the addiction medication she gets from a nearby clinic.

“That’s saving my life right now,” she said.

The Medicaid expansion has also allowed Ohio and other states to move beyond the old patchwork and begin building more comprehensive systems to care for patients addicted to heroin and other opioids, bringing together medical care, counseling and medication treatments.

“It just makes more sense to do this through coverage because you can connect people to the full array of services they need to deal with substance abuse,” said Greg Moody, who helps lead Ohio’s effort as head of the governor’s Office of Health Transformation.

Thanks to the extra Medicaid funding, the state in recent years has also opened new treatment programs in jails and prisons and new courts to focus on defendants with substance abuse issues.

“These are addressing longtime gaps in our system,” said Tracy Plouck, who directs Ohio’s mental health and substance abuse programs.

In Cincinnati, where hospital emergency rooms are still seeing close to 200 drug overdoses a month, treatment options are also expanding.

BrightView Health has opened three clinics in and around Cincinnati in the last four years, and Ryan and his partners plan to open a fourth soon.

There are encouraging signs across Ohio that the efforts are bearing fruit, as patients like Neeley get into treatment.

Nearly three-quarters of new Medicaid enrollees with a substance abuse disorder reported better access to care after getting coverage, according to the recent state study.

But significant gaps remain, researchers found, with just 1 in 5 of those with an opioid addiction getting recommended medications.

Many experts caution that the gains are tenuous.

“We have never before had a sustained effort to confront substance abuse,” said Ryan, in between seeing patients at one of his clinics. “We are just beginning to get some momentum to change the whole paradigm for patients.… Without Medicaid coverage, we couldn’t continue.”

If Republican healthcare legislation rolling back Medicaid is enacted, states like Ohio would be faced with either scaling back Medicaid coverage for people suffering from substance abuse or cutting other government services to continue the effort to control the opioid crisis.

For her part, Neeley shudders at the thought that First Step Home would have to turn away mothers like her.

“They gave me back my life,” she said, as she held her 2-year-old daughter. “There are miracles that happen here. I’ve seen women reunited with their children … and I think maybe someday that could be me.”

ALSO

Column: Why does a California senator want to make it harder to catch bad doctors?

Ohio officer suffers accidental overdose from powder on shirt after drug arrest

Trump taps Chris Christie to lead fight against nation’s opioid addiction crisis

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.