Dramatic improvements in campaign technology reshaped the midterm election; the presidential race awaits

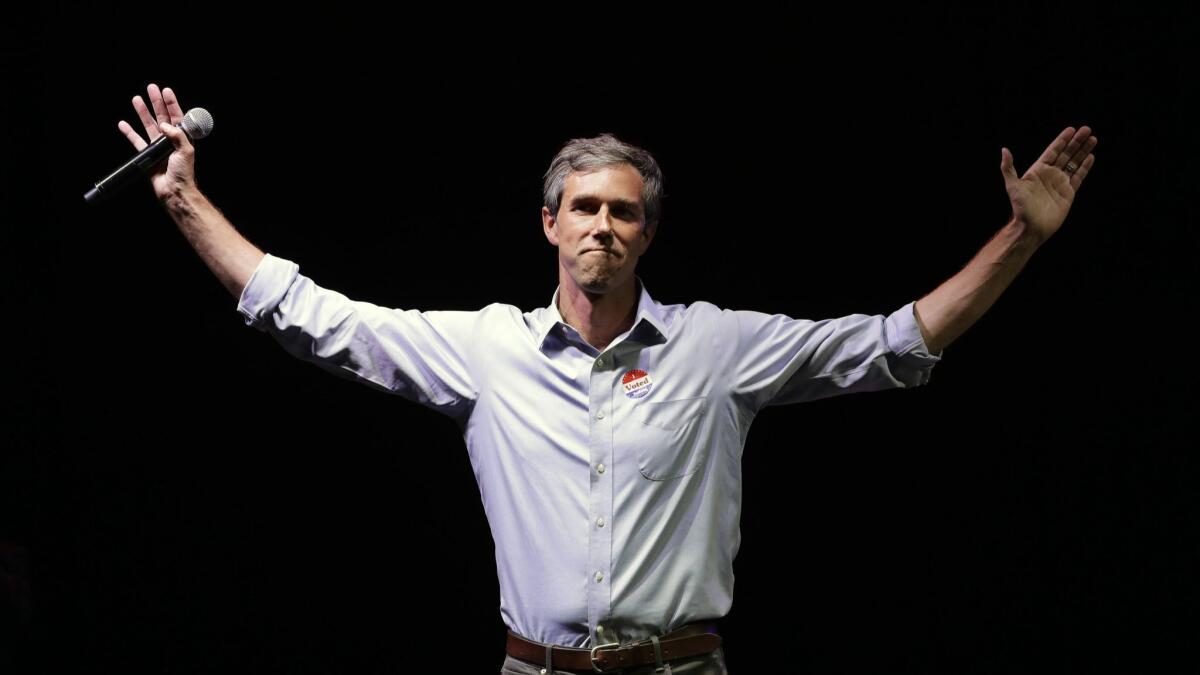

Reporting from Washington — Beto O’Rourke launched his Senate campaign with low name recognition, crumbs in the bank, and a widespread belief among pundits and operatives that he would finish his long-shot bid to unseat Sen. Ted Cruz where he started: in obscurity.

He ended up coming closer to victory in Texas than any Democratic challenger in 40 years.

More than charisma and a charged electorate enabled the Texas congressman to get close. Like dozens of other once-obscure Democratic candidates in the last election, he was able to catapult from also-ran to electoral phenom in part by raising record-shattering amounts of small-donor cash and mobilizing unprecedented armies of volunteers. Technology played an outsized role.

“Things are possible that weren’t really possible before,” said Alfred Johnson, co-founder of MobilizeAmerica, a platform widely used by groups on the left to organize volunteers in this election cycle.

Now, the online platforms that reshaped the midterm elections are likely to do the same to the presidential race, as some two dozen hopefuls prepare for a frenzied and prolonged Democratic primary.

The new technologies could give fresh-faced candidates with appeal to grass-roots donors a major advantage over older, more established names.

They could also allow multiple candidates to keep their campaigns alive deep into the primary season, much as Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) did in 2016 with his challenge to Hillary Clinton — a prospect that worries some Democratic strategists.

A candidate like former Vice President Joe Biden traditionally would be considered a favorite because of his ties to long-standing big-money donors. But in the new campaign landscape, it could be Biden who is at a disadvantage.

“I don’t know that Joe Biden has successfully raised money online, ever,” said Nicco Mele, director of Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy. Mele helped lead one of the first tech-savvy primary campaign efforts in 2004.

“Beto has a list. He could send an email out January 1st and potentially raise $100 million in 100 days,” Mele said. “Joe Biden, to my knowledge, does not. Biden has to build the list and engage the community. That could take a year.”

The ability to raise large sums from small donors online could matter even more than usual for 2020 because of the nature of the calendar, especially California’s move to hold its primary in early March.

The cost of campaigning in California is immense, and candidates will have to move fast to build an enthusiastic network of small donors and volunteers to sustain their operations or risk having their campaigns end almost at the beginning.

Conversely, those who do successfully build such an operation may find, as Sanders did, that small donors will stay with them more patiently after losses than major donors traditionally have.

Whether that is healthy for the party is an open question.

“Tons of candidates are going to be staying in for a long time,” said Tim Lim, a Democratic strategist and founder of Blue Digital Exchange, a trade association for progressive digital professionals. “We will see what that means for the Democratic Party.”

These changes are coming about because advances the Democrats have made in campaign technology have forged a path for the most unlikely of candidates to quickly build and deploy infrastructure long accessible to only a select few.

“We made bigger strides forward in campaign tech over the past two years than we have in any cycle since I have been in politics,” said Betsy Hoover, who helped direct digital operations for Barack Obama’s reelection and now is a partner at Higher Ground Labs, an incubator for progressive political tech.

“Even smaller campaigns with smaller footprints were able to reach massive numbers of people,” Hoover said.

That’s a lesson for the next round, said Adam Bozzi, a spokesman for End Citizens United, the campaign finance advocacy group that raised millions to propel a select group of candidates.

“What we saw is you didn’t need to be a national brand name to build a strong grass-roots fundraising network,” he said. “You didn’t even need to be someone people would perceive would catch fire.”

“There is an opportunity for any number of candidates to engage with voters in the right way and run a viable campaign.”

After the predominantly liberal tech industry was rattled by Trump’s electoral victory, engineers and entrepreneurs stepped up efforts to optimize the left’s campaign machinery. They scrutinized the infrastructure, including fundraising, polling and voter engagement. New funding streams were tapped to expand the universe of political tech start-ups.

The Democrats started from a strong foundation — ActBlue, the fundraising powerhouse that propelled Sanders’ campaign by enabling small donors to give again and again with the ease that Amazon Prime gives customers reordering shampoo.

This campaign season, a handful of new off-the-shelf tech tools helped candidates and the grass-roots organizations backing them ramp up the amount of money flowing through ActBlue to double the 2016 level — stunning Democratic operatives.

“The growth has been exponential,” said Erin Hill, ActBlue executive director. “It changes the kind of campaign you can run.”

Whoever jumps into the presidential contest will likely move fast to leverage new tech tools that enabled candidates in the midterms to accelerate the flow of small-donor funds. Those tools helped candidates boost the effectiveness of their online messaging, target the right donors and persuade those donors to keep giving.

Firms such as Change Research drove down the cost and improved the quality of online polling, allowing scores of candidates access to valuable targeting and messaging data that was once out of reach for all but the most well-heeled campaigns.

The start-up Swayable used analytics developed with the input of thousands of online survey participants to track how voters and potential donors were responding to different variations of progressive online messaging.

Other platforms enabled candidates to move quickly whenever a potential fundraising moment emerged. The White House Rose Garden celebration after House Republicans voted to repeal the Affordable Care Act, for example, enraged progressives and moved them to dig into their pockets.

Trump’s outbursts on Twitter, his unrestrained attacks on political opponents and special counsel Robert S. Mueller III, and the scandals dogging several of his agencies trigger such fundraising opportunities each week.

Candidates are also able to harness the energy cultivated by big, national grass-roots groups — some of which sprouted only after Trump was elected — in ways that were not previously possible. Groups such as MoveOn, Swing Left and Indivisible leaned on MobilizeAmerica to bring out record numbers of volunteers to knock on doors, staff phone banks, and text voters and potential donors.

The company was founded by two entrepreneurial Democrats who did a deep examination of the energy progressive groups were harnessing that was getting lost in the clunky bureaucracy of campaigns. They came up with a formula for luring potential canvassers and other volunteers in, signing them up for shifts and nudging and encouraging them through the process so that they showed up.

MobilizeAmerica seamlessly guided hordes of volunteers from grass-roots groups to phone banks and canvassing events for their favored candidates without the process getting gummed up by balky efforts by campaigns to register and track them using clunky databases.

The platform may have tipped the outcome in the Central Valley race in which Democrat T.J. Cox prevailed over Rep. David Valadao by just 591 votes. Canvassers enlisted for Cox through MobilizeAmerica knocked on 28,500 doors in the district, according to data shared by the company.

The large grass-roots organizations that used MobilizeAmerica and ActBlue to help House candidates will likely play a different role in the presidential primaries, but they will still loom large.

Many of the groups won’t make endorsements until the field has narrowed, if at all. But they have become so effective at grabbing the attention of masses of activists that even an email blast or a telephone town hall that lays out where all the candidates are on an issue presents a rich opportunity for candidates to raise money and build supporter lists.

“There are a lot of smart and thoughtful people out there who just don’t have a lot of time,” said Ethan Todras-Whitehill, co-founder of Swing Left. The group doesn’t raise money for primary candidates, but its surprising success raising millions of dollars online for general-election races in advance of the primaries has made it a fundraising pioneer that candidates are studying closely.

“You can’t sell them snake oil,” Todras-Whitehill said. “But if you do some smart thinking and put something together that is easy to do and really impactful, that is exactly what they looking for.”

The latest look at the Trump administration and the rest of Washington »

More stories from Evan Halper »

Twitter: @evanhalper

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.