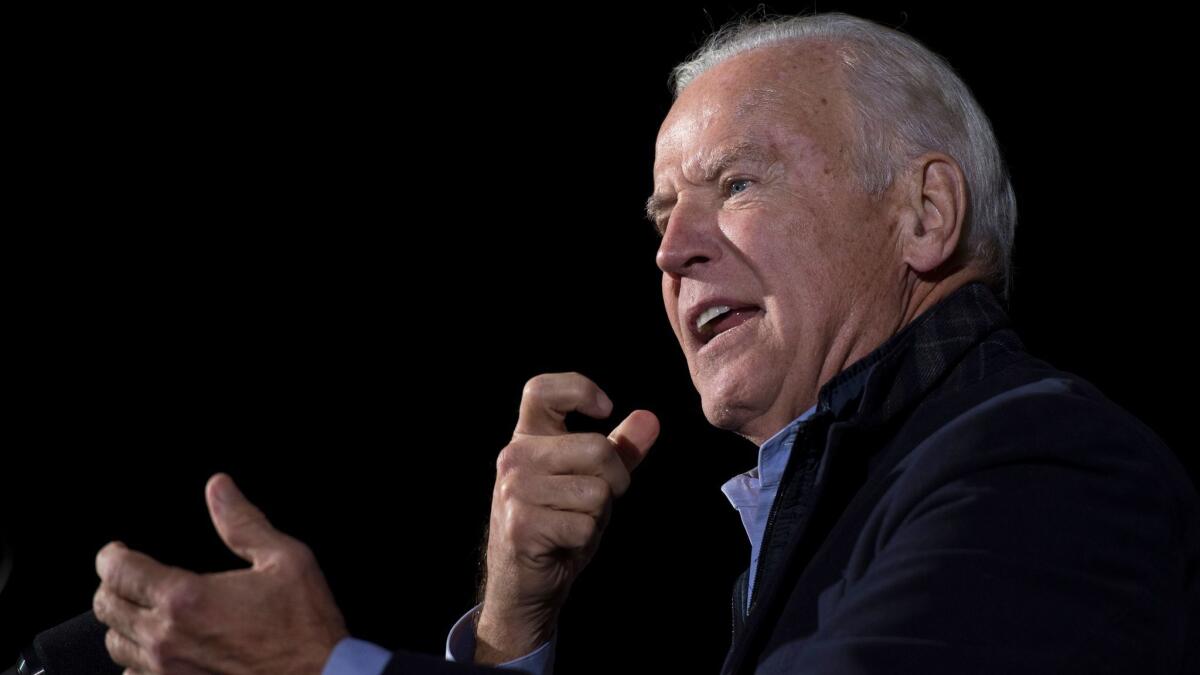

As Democrats ponder their future, Joe Biden makes a plea for a focus on the middle class

Washington — Over a career in elected public office lasting more than 46 years, Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. has seen campaigns from the rudimentary, family-run effort that first launched him unexpectedly to the U.S. Senate as a 29-year-old to the sophisticated, data-driven juggernaut that helped elect him and Barack Obama twice to the nation’s highest offices.

But rarely has he trusted anything as much as his own gut instinct, attuned to the middle- and working-class sensibilities of his former neighbors in towns like Scranton, Pa., and Claymont, Del.

And so as he sat in his office one day in October and watched footage of a Donald Trump rally in Wilkes-Barre, Pa., not far from his childhood home, Biden sensed trouble.

“Son of a gun. We may lose this election,” Biden said, recalling his reaction during an interview in his West Wing office.

“They’re all the people I grew up with. They’re their kids. And they’re not racist. They’re not sexist. But we didn’t talk to them.”

They’re all the people I grew up with. They’re their kids. And they’re not racist. They’re not sexist. But we didn’t talk to them.

— Joe Biden, vice president

Now, as the Democratic Party struggles to understand what went wrong in an election that left them with the least power in state and federal offices in decades, that same instinct leads Biden to offer a diagnosis and a prescription for what he sees as a more successful approach, one which pushes back, if ever-so-gently, against a powerful current in Democratic politics.

It begins, in typical Biden fashion, with a reference to family wisdom.

“My dad used to have an expression. He said, ‘I don’t expect the government to solve my problems. But I expect them to understand it,” Biden said.

“I believe that we were not letting an awful lot of people — high school-educated, mostly Caucasian, but also people of color — know that we understood their problems.”

There’s “a bit of elitism that’s crept in” to party thinking, he worries, setting up what he sees as the false impression that progressive values are inconsistent with working-class values.

“What are the arguments we’re hearing? ‘Well, we’ve got to be more progressive.’ I’m not saying we should be less progressive,” he said, adding that he would “stack my progressive credentials against anyone” in the party.

“We should be proud of where the hell we are, and not yield an inch. But,” he added, “in the meantime, you can’t eat equality. You know?”

He also distinguishes what he describes as the middle-class agenda that President Obama has put forth from the more populist, anti-Wall Street message that helped power Bernie Sanders’ rise in the Democratic primary.

“I like Bernie,” Biden said, adding he agrees with the Vermont senator on many issues. “But I don’t think 500 billionaires caused all our problems.”

::

It was election eve, and Biden had just concluded the last of 83 campaign events he would headline on Hillary Clinton’s behalf. Something once again didn’t feel right.

Stepping off the stage after an at-times sentimental appearance in northern Virginia with Sen. Tim Kaine, the man he hoped would succeed him, the vice president shared a nagging concern with aides: Any enthusiasm among the crowd of several thousand was not about the party’s presidential nominee.

“You didn’t see any Hillary signs,” Biden recalled. “Every time I talked about Hillary they listened. But …”

Biden’s speech that night mirrors his message to Democrats now.

“God willing we’re going to win this, but there’s a lot of people who are going to vote for Donald Trump,” Biden told the crowd. “We’ve got to figure out why. What is eating at them? Some of it will be unacceptable. But some of it will be about hard truths about our country and about our economy. A lot of people do feel left out.”

Speaking weeks later beside a crackling fireplace in his West Wing office, Biden was more blunt.

“I was trying to be as tactful as I could in making it clear that I thought we constantly made a mistake of not speaking to the fears, aspirations, concerns of middle class people,” he said.

In the campaign, “you didn’t hear a word about that husband and wife working, making 100,000 bucks a year, two kids, struggling and scared to death. They used to be our constituency.”

When Biden considered running himself in 2016, he and his aides envisioned a campaign that would combine the continued popularity of the Obama administration in which he’d served with his reputation as a middle class warrior and his affable — often blunt — persona.

In a memo to Biden’s vast network of former staff and supporters, a top aide wrote that a Biden campaign would be “optimistic,” a “campaign from the heart” — and, naturally, “it won’t be a scripted affair.”

If Biden entered the race, former Sen. Ted Kaufman wrote in the memo, which quickly became public, it would be because of “his burning conviction that we need to fundamentally change the balance in our economy and the political structure to restore the ability of the middle class to get ahead.”

Biden, of course, did not run. The emotional toll of the death that spring of his eldest son, Beau, made a campaign an impossibility.

But the clarity of Kaufman’s memo contrasts notably with Biden’s critique of Clinton’s campaign. In the interview, Biden pointed to questions that came even from members of Clinton’s inner circle, revealed in emails made public by WikiLeaks, about whether the Democratic front-runner had figured out why she was running.

“I don’t think she ever really figured it out,” Biden said. “And by the way, I think it was really hard for her to decide to run.”

Clinton’s decision to run did not reflect raw ambition or a desire to move back to the White House, he said, calling those characterizations of her unfair. Instead, he said, he saw her decision to run as ultimately stemming from a sense of duty and her belief that her victory “would have opened up a whole range of new vistas to women” in a similar way that Obama’s had for African Americans.

“She thought she had no choice but to run. That, as the first woman who had an opportunity to win the presidency, I think it was a real burden on her,” he said.

It was one of several times Biden went out of his way to emphasize that he doesn’t see Clinton as singularly responsible for the November defeat. It was, rather, the result of a combination of factors that includes the unique candidacy of the president-elect.

The core of the Democratic agenda is popular with the American people, Biden said, but was not always communicated effectively to those who would benefit from it.

As he said during the campaign, Biden became frustrated with coverage of the race that seemed devoid of substance, based more on documenting an unending series of controversial public statements from Trump that “sucked all the oxygen” that should have been devoted to issues.

Asked about comparisons between his and Trump’s freewheeling rhetorical style and economic message, Biden seemed cautious to avoid directly criticizing the president-elect.

“I think there’s a difference between authenticity and …,” he said before pausing to choose his words carefully. “I don’t think I’ve ever said anything that I didn’t believe. Now maybe I shouldn’t have said it. But I believed it.”

What he more clearly disputes is the notion that Trump was any more successful than Clinton in offering both empathy and hope to economically distressed Americans.

“I don’t think he understands working-class or middle-class people,” Biden said. “He at least acknowledged the pain. But he played to the prejudice. He played to the fear. He played to the desperation. There was nothing positive that I ascertained when he spoke to these folks that was uplifting.”

::

The party’s defeat leaves the Democrats without a clear leader. But Biden says he’s not going anywhere, which he means literally and figuratively. Like Obama, he is planning to live in Washington, at least part time, after moving out of the vice president’s residence on Jan. 20.

The presence of both the former president and the former vice president in the capital will be historically unusual. But Biden’s decision to remain nearby is, like many he’s made in his political career, largely driven by family. His wife, for one, will continue teaching at a community college in Virginia.

Still, the decision to live even part time in the nation’s capital will give him proximity to the unfolding Trump administration and the decision-makers and media figures interacting with it.

And it will allow him to continue stoking the political fires — he seems to revel in the notion that he might be fit enough to challenge Trump in four years, when he would be 77 and Trump 74, although he has not publicly committed to any plans.

Others close to him are less reticent. “Biden’s going to be the country’s conscience,” said Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, the former chair of the Democratic National Committee who forged a close relationship with him.

Biden will be freer to speak out about Trump administration actions than Obama, Wasserman Schultz said. “And he’s certainly not shy.”

For more White House coverage, follow @mikememoli on Twitter.

ALSO

American voters wanted change in 2016, but will they get the change they wanted?

Joe Biden makes the case for Hillary Clinton to working-class voters: ‘She gets it’

Biden’s ‘bittersweet’ speech packs some punches at Trump

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.