They say terrible things about Nancy Pelosi. Her response: Just win, Democrats

Reporting from Coral Gables, Fla. — The crowd outside campaign headquarters was boiling, the angry mood matching south Florida’s tropical heat, as Nancy Pelosi arrived to a shower of obscenities and crude insults in English and Spanish.

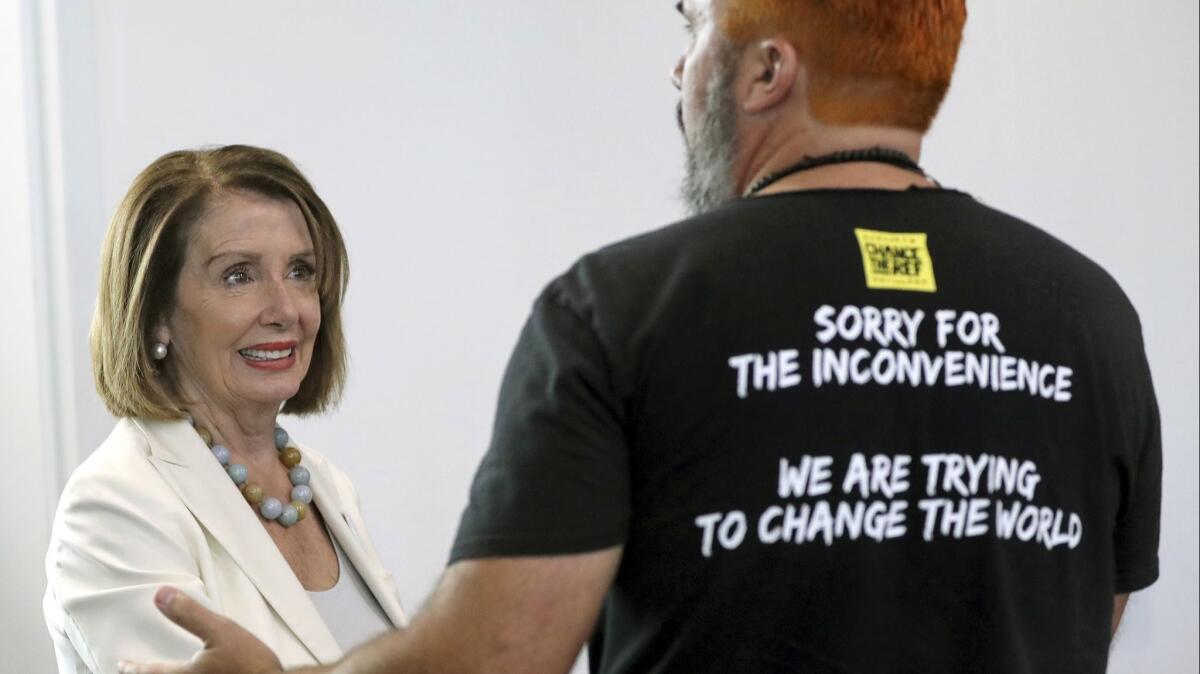

With the doors locked and police standing guard, the Democratic congressional leader delivered her exhortation to dozens of volunteers — Make those phone calls, walk those precincts, the future of America’s at stake this midterm election! — as crisp and unruffled as her white pantsuit.

Pelosi doesn’t care about the invective hurled her way, in whatever language. She doesn’t care that her face has appeared, menacing and twisted, in thousands of Republican attack ads. She doesn’t care that life is a full-time residency in travel hell — a blur of meals on the run, flight delays, a different hotel each night.

She cares about one thing, distilled in the advice Pelosi gives Democrats with any qualms about distancing themselves for political sake from the national party or its lightning-rod leader.

“Do whatever you have to do,” she tells them. “Just win, baby.”

Blue wave in Orange County relies on two ex-Republicans turned Democrats »

No one, apart from President Trump, may be more responsible if Democrats seize control of the House on Nov. 6, or fall short, than the 16-term representative from San Francisco, who has raised nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars since she was elected her party’s leader in the chamber in 2002.

Now well into her eighth decade in politics — as “Little Nancy” she helped track voters for her father, a New Deal congressman and former Baltimore mayor — Pelosi is in many ways a perfect avatar for these deeply riven times.

She is a heroine, greeted with the kind of gushing adoration reserved for spiritual leaders and sports champions. She is a villain, cursed for obstructing the president’s will and embodying the caricature of Democrats as a bunch of effete left-wing nut cases.

She is unshakable in her self-confidence — “a master legislator and a dazzling fundraiser,” Pelosi calls herself — convinced that Republicans attack her only because she has been so very effective.

She also shoulders a sizable chip over every slight, real or imagined, she ascribes to gender or resentment over the power and prominence she enjoys in what remains, in many ways, a man’s world. (“I don’t think of them as anti-women,” Pelosi said of NBC News, expressing puzzlement the network keeps a running tally questioning whether she has the votes to be elected speaker if Democrats win the House.)

She is tireless. During a two-day campaign swing last week she was up at dawn and starred at a healthcare forum in Lawrence, Mass., a Harvard seminar, a meeting with gun control advocates, the get-out-the-vote rally in Coral Gables and a cocktail reception for south Florida Democrats. Grazing, she snatched a slice of prosciutto before delivering her remarks to several dozen patrons before a high-rise view of the Atlantic.

There were fundraisers for breakfast, lunch and dinner and, in between, a steady stream of phone calls and text messages with staffers, congressional colleagues and political donors.

On a good day, she makes it to bed around midnight, after rewarding herself with dark chocolate, a sudsy bath and the New York Times crossword puzzle.

Don’t agonize, organize!

— House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi’s midterm election mantra

Even as Pelosi signals an end point to her historic leadership run, she shows no signs of slowing down. If anything, she’s traveling at a more frenzied pace — 25 cities in the first 18 days of October — all to thwart a chief executive she views as not only reckless and dangerous but, frankly, mind-boggling.

“Trump, president of the United States,” she said, her voice dropping a register as if weighted by the words. “Oh, my God.”

::

Pelosi, 78, is not a particularly gifted or dazzling campaigner.

Her stump speech is serviceable, a mix of hyperbole and grandiose reference here and there to Lincoln, Shelley, De Tocqueville, Thomas Paine or John F. Kennedy’s “ask not” inaugural address, which, she notes, she attended as a teenager.

She lands on a slogan — this election it’s “Don’t agonize, organize!” — and repeats it with jackhammer persistence: in a “Dear Colleague” letter to fellow Democrats, to healthcare providers in Massachusetts, with the shake of a fist to campaign workers in Florida.

Pelosi’s power lies in her presence as a breaker of glass ceilings, the first and only woman to serve as speaker of the House, the third-most-powerful position in the U.S. government.

Mothers greet her as an inspiration to their daughters. Young women crowded in like groupies at the Democratic outpost in Coral Gables, clamoring for selfies, which Pelosi obliged with a pose and camera-ready smile. At a Miami Beach fundraiser, a 20-something accented her brown cocktail dress with a rainbow Nancy Pelosi wristband — a gift, she said, a friend snagged from a San Francisco gay pride parade.

The Democratic leader is ever gracious. But below the surface she seems far less taken with adulation or much else besides the nuts and bolts of winning congressional campaigns and passing legislation.

In Coral Springs, near the site of February’s mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, Pelosi sat attentively through a heart-wrenching session with about a dozen students and parents, the air thick with sorrow and grief. When a fire engine roared past the City Hall conference room, siren screaming, several visibly tensed.

But Pelosi remained placid, growing animated only after talk turned to get-out-the-vote efforts and political organizing around the newly energized gun control movement. “You are a blessing,” she told the survivor-activists. “We will get this done.”

With half a dozen TV cameras and a clutch of reporters looking on, she vowed to push for universal background checks for gun purchases, part of a multipronged agenda if Democrats take control of the House.

Other items she routinely ticks off include lowering prescription drug prices, creating middle-class jobs through a massive infrastructure-rebuilding program, reforming the campaign finance system to boost the influence of small donors, and protecting “Dreamers,” the young people brought illegally to the United States as children. (Impeaching Trump, she says, is a nonstarter without Republican support, which seems highly improbable.)

All that remains a wish list, of course, unless Democrats also take control of the Senate, a considerably longer shot than winning a House majority. Even then, Trump has shown little inclination to act on any of those initiatives, much less sign legislation passed by the opposition party.

But the equation can shift drastically, Pelosi said, depending on who wields the House gavel.

As speaker she was no mere token. Under President George W. Bush, Pelosi was instrumental in passing the 2008 bailout that saved the economy from collapse. In 2010, working with President Obama and a Democratic Senate, she pushed through the Affordable Care Act, greatly expanding the availability of healthcare after decades of failed Democratic efforts.

Once a burden on the party, the law is now a centerpiece of Democratic campaigns, embraced by voters after Republicans repeatedly tried and failed to repeal the law they deride as “Obamacare.” As she travels the country, Pelosi is enjoying something of a belated victory lap, nodding and clapping along in agreement as speakers extol her achievement.

She is unabashed and unapologetic. “Self-promotion is a terrible thing,” she told a group of students at Harvard’s Institute of Politics, “but sometimes somebody has to do it.”

::

When Pelosi arrives in a new city, she’ll flip on the television set. Not to watch any particular program — her main viewing pleasure is sports, and any will do — but to monitor political advertising. It’s a quick way to assay the campaign landscape, and if those ads feature some wicked representation of herself, she’s not at all bothered.

Growing up in a political family (like her father, an older brother served as Baltimore mayor) Pelosi grew accustomed to the tooth-and-claw nature of campaigns. “Throw a punch, take a punch,” her father used to say.

Pelosi offers her own variation. “I’m in the arena,” she said over coffee between campaign stops as she invoked Theodore Roosevelt’s famous maxim. “This is what this is about. People are going to throw punches. Don’t be surprised.”

Her unflappable response, several intimates said, is the same in private. None could recall Pelosi ever losing her composure, however nasty or personal the attacks on her looks, her intelligence or her capabilities.

“It goes against her political DNA,” said former lawmaker John Burton, himself an institution in San Francisco politics, who has known Pelosi for decades. “She’s focused on getting things done, and it doesn’t allow her to stand in a corner and wring her hands and go” — here his pitch turned to a whiny falsetto, as if giving voice to the mockery — “‘Oh, did you hear the terrible things Republicans say about me. I can’t do this anymore!’”

At Harvard, on a small stage before about 200 students and guests, Pelosi appeared most in her element as she delivered a tutorial on the legislative process and life lessons for anyone considering a career in public office. “Know your why, know your what, know your how,” she advised. “That’s how you can get something done.”

Even before that friendly audience, Pelosi couldn’t avoid a question from a young man asking, implicitly, whether senior lawmakers such as herself weren’t preventing new ideas and fresh leaders from emerging in Washington. Her response, that a group of legislators in their 30s were going around the country listening to millennials share their concerns, landed with a nearly audible thud.

Quietly, though, Pelosi has been grooming potential successors — among them Reps. Adam B. Schiff of Burbank, Ben Ray Lujan of New Mexico and Cheri Bustos of Illinois — while publicly describing herself as a transitional figure, or a bridge to a new generation of Democrats.

Will California flip the House? The key races to watch »

The argument for fresh blood is nothing Pelosi hasn’t heard before.

When she ran for House Democratic leader the first time, at age 62, she faced Harold Ford Jr., then a 32-year-old Tennessee congressman who sought to leverage the old-vs.-new argument in a bid to stop Pelosi’s ascension. She won easily.

The jibes aimed at her supposed flakiness began the first time she ran for office, in 1987. Overnight, Pelosi went from relative anonymity to a figure taunted on billboards across San Francisco asking voters if they wanted “a legislator or a dilettante?”

Pelosi long ago laid that question to rest, along with any doubt she can both throw and take a punch, whatever direction it comes.

So long as Democrats win back the majority, she doesn’t care.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.