California on verge of unprecedented clout in Congress, but McCarthy and Pelosi barely speak

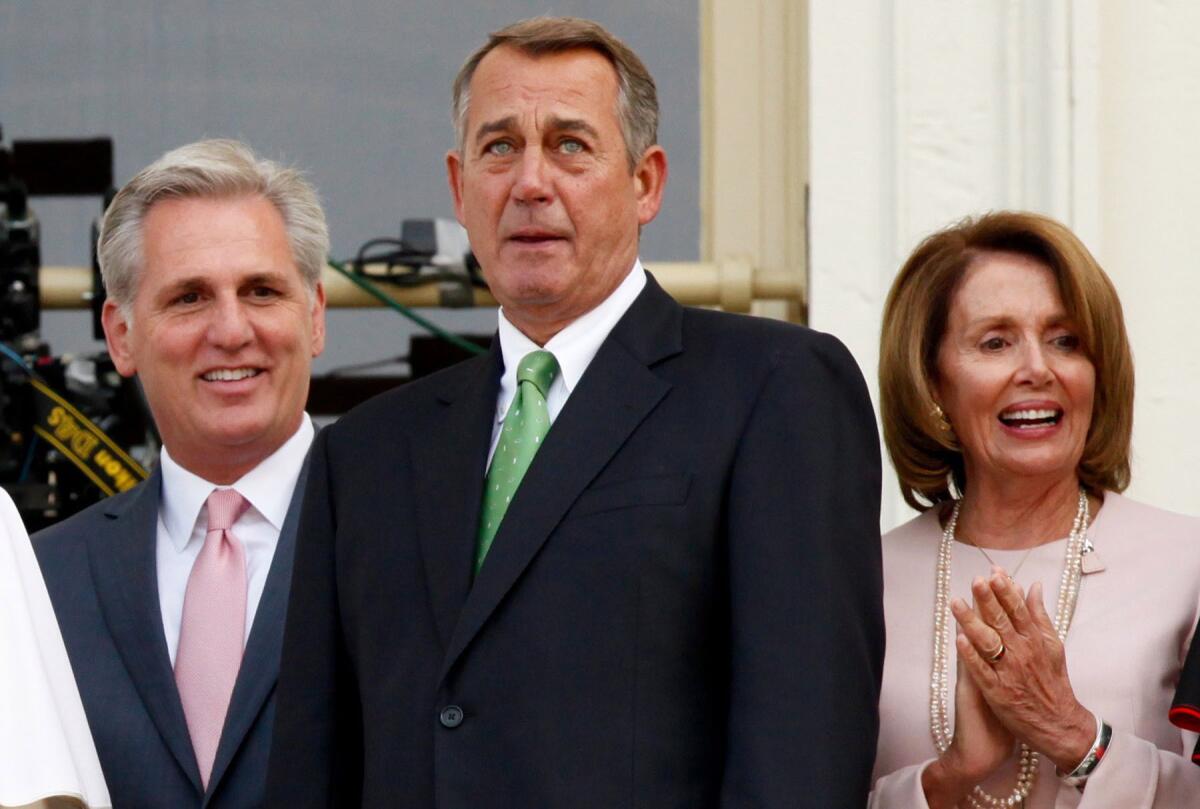

Speaker of the House John Boehner is flanked by House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy and House Democratic Leader Rep. Nancy Pelosi the balcony of the US Capitol building during an event with Pope Francis.

Reporting from Washington — When Kevin McCarthy spoke at a California Republican convention a few years ago, he regaled the crowd with stories about his tense relationship with Nancy Pelosi: The Democratic leader, he said, greeted him with a sneering “he-llo Kevin” every time she saw him, the way Jerry Seinfeld used to greet his nemesis, Newman.

He clearly had the sentiment right, but might have exaggerated how often the two speak.

McCarthy and Pelosi are about to make history. If McCarthy becomes speaker of the House, as is widely expected, his ascent would mark the first time in history that both the speaker and minority leader of the chamber have hailed from the same state.

Several colleagues said they can’t recall ever seeing the two together.

In another era, holding the top positions on both sides of the political aisle might have brought a state billions of dollars in highway projects, research centers or military bases. But in a country where all politics is increasingly national – not local – and polarized by party, few on Capitol Hill expect special returns for California from a McCarthy-Pelosi duo.

The lack of a relationship between the two epitomizes the deep partisan divisions that have paralyzed Congress’ ability to pass major legislation, or even keep the government open.

“There hasn’t been a time since the Civil War when this place has been so partisan,” said Rep. Brad Sherman, a Democrat from Sherman Oaks. “There’s never been a time where ideology outweighed geography by a greater ratio.”

Both party leaders have flaunted their lack of personal ties.

Pelosi acted as if she barely knew McCarthy during a news conference last year, when McCarthy was in line to become the No. 2-ranking Republican behind Speaker John A. Boehner of Ohio.

“I, myself, work with Speaker Boehner,” she told reporters, adding that she wasn’t sure if she’d ever been in a closed-door meeting with McCarthy, who by then was No. 3 in the House GOP leadership.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Politics newsletter >>

On McCarthy’s side, aides are happy to let it be known that he and Pelosi seldom talk. As he runs for speaker, any hint of a relationship with the liberal from San Francisco could poison his reputation among conservatives.

“There is no relationship,” said an aide to McCarthy.

The divide reflects their constituencies. The distance in miles (about 250) only begins to describe the gap between Pelosi’s home in San Francisco and McCarthy’s in Bakersfield. In climate, culture and politics, the two cities could easily be parts of different states.

California’s 53-member congressional delegation – the largest in the country – often behaves as if that were the case.

California lawmakers share statewide concerns, including a four-year drought that has dried crops and prompted water restrictions, but they rarely collaborate on legislation, or even have lunch together. The 14 Republicans get sandwiches once a week, either in McCarthy’s office or the members’ private dining room. The state’s 39 Democrats dine on Wednesdays down the hall from the dining room, choosing salad or fried chicken from a buffet.

It was considered noteworthy when Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-San Jose) organized a bipartisan wine-and-cheese gathering in June, on a Capitol balcony.

“I always was envious to hear that other delegations would meet together on a bipartisan basis, weekly,” said former Rep. Henry A. Waxman, a Beverly Hills Democrat who retired last year. “Only on rare occasions did we have bipartisan meetings.”

As in so many other fields, California has set the trend in partisanship. The state’s congressional delegation was already holding separate meetings before Waxman first came to Congress in 1975, he recalled. Now, that sort of sharp political split has spread.

Even today, there are exceptions. The two senators from New Hampshire, Democrat Jeanne Shaheen and Republican Kelly Ayotte, for example, have pushed to increase home heating assistance for the poor, prevent local military cutbacks and protect the fishing industry. In a closely divided state, both see a benefit in appearing cooperative.

McCarthy and Pelosi, by contrast, not only come from heavily partisan districts, their roles as national leaders of their parties involve vigorous defense of their ideologies.

In addition, the two often find themselves on opposite sides of state concerns.

McCarthy views the drought through the eyes of his district’s farmers and has pushed to roll back environmental regulations to get more water for crops. Pelosi sees environmental protection as a top priority.

Though some believe McCarthy would like to see an immigration overhaul, he has avoided appearing sympathetic, given the opposition among House Republicans.

The two could also hardly be more different on a personal level.

“If you were to contrast Bakersfield from San Francisco, you get a pretty good contrast between Kevin McCarthy and Nancy Pelosi,” said Dan Lungren, the Republican former congressman and state attorney general.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

Pelosi is a sophisticate, reared on her city’s progressive politics, who comes from a longtime Baltimore political family. She is known for having an iron grip on her caucus that allowed her to push liberal legislation when she was speaker and maximize her party’s leverage when she lost her majority.

McCarthy is known for a sharp understanding of electoral politics, but he and other party leaders have been unable to corral the GOP’s rebellious factions, who have resisted attempts to compromise with Democrats.

To partisans in the state, their ideological differences matter more than the state’s shared issues.

“The fact is, she’s someone who represents the liberal left,” said Rep. Dana Rohrabacher, a Republican from Costa Mesa. “She might as well come from New York City or Massachusetts.”

Rohrabacher said even if his colleagues had better personal relationships, little would change. He didn’t think much of Lofgren’s wine-and-cheese party.

“It certainly made us feel better about ourselves,” he said, “but didn’t move any policy along toward enactment.”

McCarthy’s move into the speaker’s office, however, may finally force him and Pelosi to form a relationship, and soon.

Because House Republicans have had such a hard time agreeing on political strategy in recent years, Boehner repeatedly needed Democratic votes to pass crucial bills. Democrats expect McCarthy will similarly need them.

Pelosi’s spokesman, Drew Hammill, said she hoped to create a dialogue with McCarthy because “working with Democrats will remain the only sustainable path to moving our country through the Republican calendar of chaos that lies before Congress this fall.”

John Lawrence, a former chief of staff to Pelosi and longtime congressional aide, said the onus would be on McCarthy, because he needs Pelosi more than she needs him. A warm personal connection probably won’t matter, he said, but the two will need to understand each other before the next crisis.

“Congressional relations aren’t about liking people,” he said. “Congressional relationships are about trust. It’s very hard to form trust in the midst of a battle.”

Staff Writers Evan Halper and Michael A. Memoli contributed to this report.

For more on California’s representatives in Washington, follow @NoahBierman

ALSO

Planned Parenthood chief takes on Republican critics in emotional hearing

Water, 2015, California: The no-good, very bad year -- now, ‘pray for rain’

L.A. County adds $50 million to funds for fighting homelessness

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.