Returning to Texas, Cruz reset his career and created a political launchpad

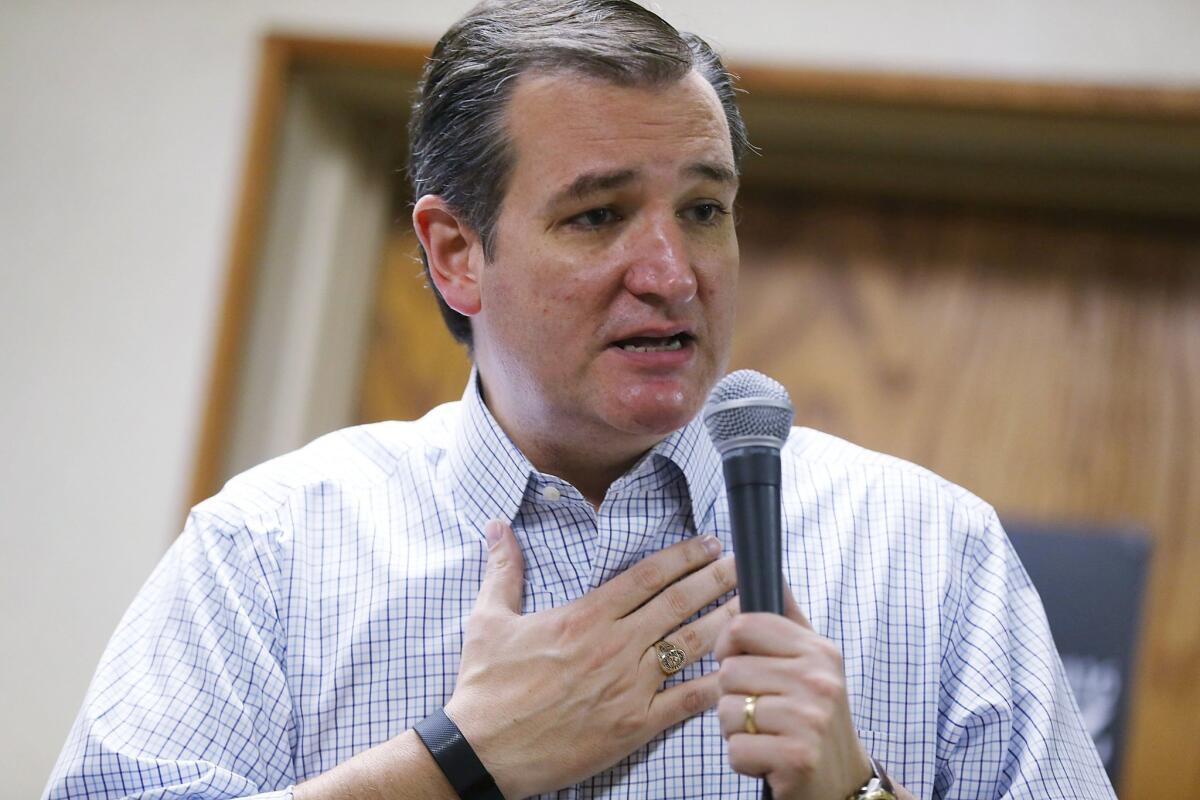

Republican presidential candidate Sen. Ted Cruz campaigns in Iowa.

Reporting from Washington — Ted Cruz was 31 and working in the George W. Bush administration, yet he felt his career had flat-lined. The Ivy Leaguer with the superstar pedigree and no shortage of confidence had figured he’d be a top presidential advisor by then, but by his own later admission, he had alienated too many colleagues.

That’s when Cruz got a call that would return him to Texas for a career reset. Over the next five years, he turned the relatively obscure position of state solicitor general into a political launchpad so powerful that today, at 46, he is a senator and has become Donald Trump’s main rival for the GOP presidential nomination.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

During his tenure as Texas’ chief appeals lawyer, from 2003 through 2008, Cruz demonstrated the qualities that have made him loved and loathed on the national stage. He showed how to distill complex legal issues in a way that attracted public attention -- and often won cases. He drew hard ideological lines that pushed the limits of conservatism and foreshadowed his own party’s turn to the right. He showed drive, creativity and entrepreneurial energy.

He also displayed an ego and talent for self-promotion that expanded the influence of his office even as it drew resentment from some colleagues and subordinates, who say he was petty and inflated his role as he lusted for the cameras.

Cruz appeared nine times before the U.S. Supreme Court, winning praise for his legal skills. Assessments of his interpersonal skills are more varied. Some who worked closely with him liked Cruz and considered him a mentor. Other former attorneys in his office offered harsher accounts, calling Cruz an arrogant and vindictive boss who never hid the belief that he was the smartest person in the room. Most were unwilling to speak on the record, citing fears of retribution.

Critics pointed to Cruz’s propensity for putting his cowboy boots on their desks, forcing them to stare at his heels instead of his face as they talked. He reserved a prime office for himself on the seventh floor, where his subordinates worked, but kept a primary office with fellow executives on the eighth, they said. They disputed his campaign claim of having “authored more than 80 Supreme Court briefs,” saying he left the unglamorous legal writing to others.

Cruz’s campaign spokesman, Rick Tyler, called questions about who authored briefs “a silly point,” noting that judicial opinions are also often drafted by clerks.

“Cruz was lead counsel so he was responsible for the briefs and he outlined the strategy and how they were written and edited and signed off on them,” Tyler said in an email.

In large private firms and government agencies, the top attorney typically leaves legal writing to subordinates, editing and managing, not drafting. Usually, however, such executives publicly frame their role as an overseer, rather than claiming authorship.

Tyler did not challenge the specifics of other criticisms aimed at Cruz, but attributed them to the “very high standards” he set for the office.

“That challenges everyone around him to rise to the occasion,” Tyler said. “Candidly, some people don’t like that. Some people prefer a 9-5 job.”

One point beyond dispute is the latitude Cruz had to shape the job. Cruz has said several times that his boss, the man who appointed him, then-state Atty. Gen. Greg Abbott, gave him an “amazing mandate” to look across the country to “defend conservative principles,” even in cases far from Texas.

The office had been created only a few years earlier, part of a trend in which state attorneys general sought to take more active roles in influencing the Supreme Court by creating specialized teams of appeals lawyers. Cruz’s office, however, was notable for its aggressive approach of mining appeals courts across the country in search of hot cases in which they could file so-called friend of the court briefs.

“We ended up year after year arguing some of the biggest cases in the country,” Cruz told the Texas Tribune during his 2012 Senate campaign. He made, he said, “a concerted effort to seek out and lead conservative fights.”

Unlike many state solicitors, who hold ambition in the legal world, Cruz was squarely focused on a career in politics.

“The state attorney general is usually the one seeking political office,” said Neal Devins, a professor at the College of William & Mary who has studied state attorneys general and state solicitors. “The theory of the creation of these [solicitors] offices is that you want to have really good lawyers with lawyers’ sensibility as opposed to politicians.”

James C. Ho, a friend of Cruz’s who followed him in the job, said, however, that the task was perfectly suited to the man.

“He has known what his beliefs are and his desire to further them in public service his entire life,” Ho said.

Cruz built a legal record that would touch almost every conservative hot button: defending the public display of the Ten Commandments and the words “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance, fighting to expand the death penalty to people who rape children, defending the state’s Republican-drawn congressional districts. In some cases, such as a gun control dispute from Washington, D.C., Texas had little or no direct interest.

Other issues in which the state did have direct interest pushed the envelope further, including his attempt to pull back a settlement the state had made with a group of mothers to improve the Medicaid program for children, and his opposition to releasing a man who, after a sentencing error, had served six years for stealing a calculator from a Wal-Mart store.

“You’ve conceded that this sentence is unlawful?” Justice Anthony M. Kennedy demanded when Cruz argued the case. “Well, then why are you here? Is there some rule that you can’t confess error in your state?” Ultimately, the man was released, although the justices sidestepped the sentencing issue.

In some other cases, Cruz suffered clear-cut losses -- including on Medicaid and the death penalty for rapists of children. But he was often in the thick of major debates.

Those who argued with and against him say he could show a surprising pragmatism, when it helped his case.

“I didn’t have the perception that he was on an ideological crusade,” said Erwin Chemerinsky, a liberal who is dean of the law school at UC Irvine. Chemerinsky took the other side on the Ten Commandments case, the one Supreme Court case in which Cruz took the second chair and watched Abbott deliver arguments.

Ernest A. Young, a Duke University law professor who taught in Texas during Cruz’s tenure and worked with him, said he was often categorical in his judgments, but not because he failed to understand the other side’s arguments.

“Some people don’t do nuance because they don’t understand the complexity of the way the world works,” he said. “Some people don’t take nuanced positions because they really just sincerely believe in a more categorical approach. And I think that’s Ted, in politics at least. But he does understand.”

Cruz’s most important case was also his most complex: a fight against Bush, his former boss, that involved the rights of foreign nationals, international treaties and the death penalty.

The Bush administration took the side of a Mexican citizen sentenced to death for two rapes and murders in Houston. The convict, Jose Medellin, argued that he deserved a new trial because he had not been given a chance to contact the Mexican Consulate after his arrest -- a right guaranteed by a treaty the U.S. had ratified during the Nixon administration.

After Mexico won a case against the U.S. in the World Court for violating the treaty in the cases of Medellin and dozens of other defendants, the Bush administration tried to order Texas to reopen his case. The state would not give in and the issue went to the Supreme Court.

“This is a very curious assertion of presidential power,” Cruz argued to the justices.

Texas won the case, 6-3, in a decision saying the treaty could not be enforced against domestic law. It was a huge legal victory but did not seem like an easy sell on a campaign trail, given its complexity. Abbott, when he ran for governor in 2014, chose not to highlight it.

Cruz framed it as a victory for U.S. sovereignty over the World Court.

Even amid such victories, however, Cruz left little doubt that he had other goals in mind. Midway through his tenure, he was featured in a front-page profile in the Austin American-Statesman, with a headline proclaiming “his star is rising.”

In it, Cruz suggested that there were ways other than legal briefs to influence the world.

“I’m a strong believer in judicial restraint,” he said. “If you want to change public policy, run for president.”

Staff writer David Savage contributed to this report.

Twitter: @noahbierman

ALSO

A Clinton-Castro ticket gets put to an early test in Iowa

Some Republican candidates spend big on ads, with little to show for it

Obama says his bet in 2016 election is on the candidate ‘who can project hope’

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.