Sanders’ pledge illustrates how plans to curtail mass incarceration fall short

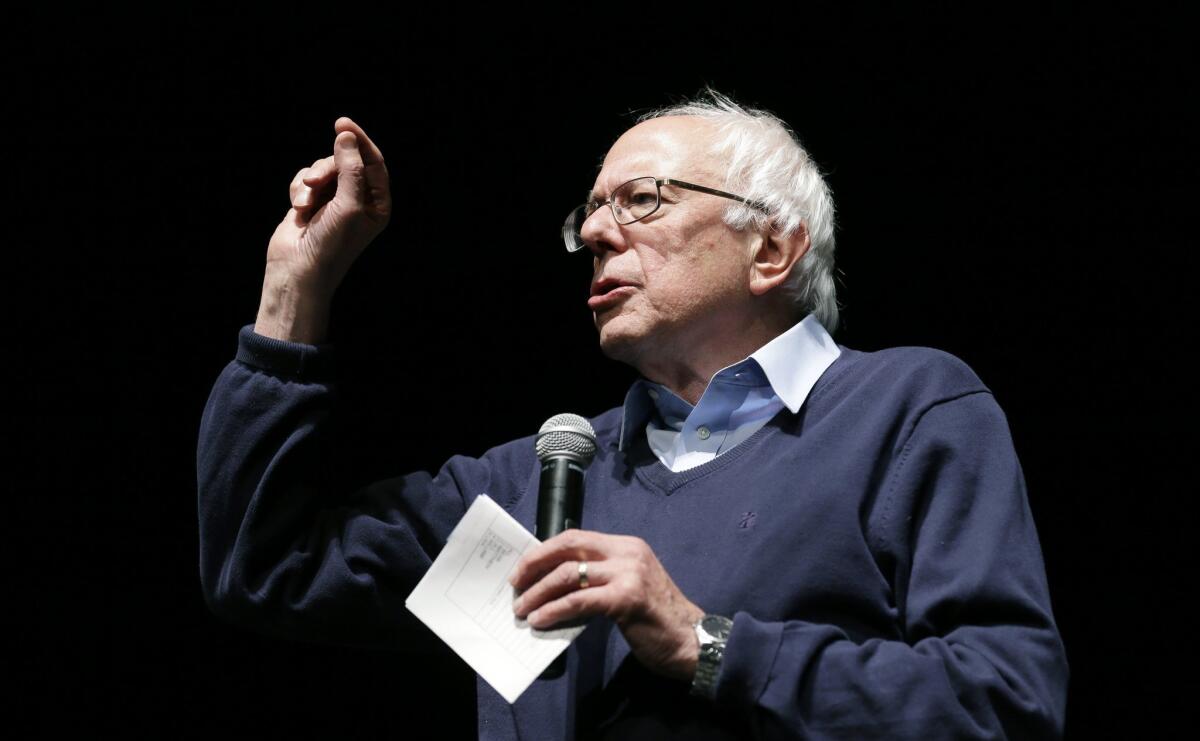

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) speaks in October in Davenport, Iowa. Sanders has pledged to dramatically reduce prison populations if elected.

Reporting from INDIANOLA, Iowa — After years of plunging crime rates, hugely expensive incarceration budgets and troubling racial disparities in criminal punishment, it has become fashionable on the presidential campaign trail to declare the United States’ uncommonly high rate of imprisonment unacceptable.

Just don’t press candidates to explain how to significantly change it.

Hillary Clinton began demanding an end to the “era of mass incarceration” almost from the day she launched her campaign. Sen. Bernie Sanders recently made a pledge that would include cutting the prison population by more than one-quarter within four years.

On the Republican side, Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky calls mass incarceration the Jim Crow of our time. Gov. Chris Christie of New Jersey says the country’s distinction of having more people locked up than any other nation is not what he has in mind when trumpeting American exceptionalism.

But ask what it would take to accomplish their goals, and all their campaigns struggle. The politically palatable prescriptions packed into bullet points in the candidates’ criminal justice plans don’t get the country even close.

Currently, the U.S. imprisons roughly 2.2 million people, according to the most recent figures from the government’s Bureau of Justice Statistics. The runner-up, China — a much larger country that places a far lower premium on freedom — is believed to imprison about 1.7 million, according to an international study.

TRAIL GUIDE: All the latest news on the 2016 presidential campaign >>

The proposals the candidates have embraced so far would make but a tiny dent in that population.

If the candidates are aware of this, they aren’t letting on.

Sanders has made the most specific promise, generating considerable excitement among liberal activists for a pledge he made earlier this month at Simpson College here.

“I don’t make a whole lot of promises,” Sanders said, “but here is one I will make to you: If elected president, by the time I end my first term, this country will not have more people in jail than any other country.”

The vow came as Sanders railed against what he characterized as a racially unjust prison-industrial complex that feeds on mass incarceration.

Scholars questioned whether Sanders was aware of just how big a promise he was making. Cutting the U.S. prison population by the more than half a million people needed to get down even to China’s number could only be accomplished by substantially softening penalties for violent criminals, they say.

Nothing in Sanders’ detailed prisons plan suggests he grasps the immensity of the task.

Sanders explained to the audience that his goal was embedded in his broader policy vision. Raising the minimum wage, eradicating youth unemployment and legalizing marijuana would substantially reduce the flow of Americans into the prison system, he said.

“If anyone thinks there is not a direct correlation between outrageously high youth unemployment and the fact that we have more people in jail than any other country on Earth, you would be mistaken,” he said. “We spend $80 billion a year locking people up. In my view, it makes a lot more sense for us to be investing in jobs and education rather than jails and incarceration.”

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

The experience of the last several decades makes clear that the relationship between crime rates and unemployment is, at minimum, more complicated than Sanders’ statement suggests. When unemployment soared during the deep recession that started in 2007, crime went down. Violent crime rose steadily from the late 1950s through the early 1990s, during good economic times and bad.

Moreover, Sanders’ emphasis on marijuana legalization fits a pattern he shares with several other candidates: a strikingly ambitious goal backed by a squishy plan.

“If we are going to make the really significant reductions that are necessary to move us out of the top spot in the world, we are going to need to move beyond proposals that just deal with low-level drug offenses,” said Ryan King, a fellow at the Urban Institute, a Washington think tank that champions shrinking the prison population.

Drug offenders make up only about one in six people in state prisons, which hold the lion’s share of people incarcerated in the U.S., according to data compiled by the institute. Few of those are low-level offenders locked up for simple possession.

To reduce the combined federal, state and local prison population by the amount Sanders’ pledge contemplates, King said, would require softening penalties for violent convicts, too.

“No candidates are talking about that,” he said.

Violent offenders convicted of such crimes as murder, rape and robbery accounted for 54% of the men in state prisons in 2013, according to statistics compiled by the Department of Justice. When the prison population surged between 1980 and 2009, for each new inmate who had committed a drug crime there were three new inmates who had committed a violent crime.

In a statement, Sanders’ campaign manager, Jeff Weaver, said that if elected, Sanders would establish a high-level commission to figure out how to reduce prison populations. A Sanders administration “will rely on both legislative and executive actions to reorient the criminal justice system,” Weaver said.

The campaign has laid out “just some elements of what those actions would be. We envision this commission would propose even more,” he said.

The numbers, however, are daunting. An online tool the Urban Institute created that charts how various policy moves would change the prison population suggests that even cutting the number of Americans jailed for drug offenses in half would shrink the state prison population by only 7% — and none of the candidates are suggesting specific changes that bold.

The report notes that mass incarceration would continue even if every single person in state prison for a drug offense were immediately released.

“There just is not an easy and politically palatable solution that reduces the prison population that much,” Patrick Egan, a professor of politics and public policy at New York University, said of the goal Sanders set for himself. “While Americans have become more supportive of criminal justice reform lately, they are still quite afraid of and quite aware of crime.”

Some advocates for reducing mass incarceration have proposed cutting sentences for violent criminals, which are longer on average in the U.S. than in many other developed countries. Few political figures have been willing to touch ideas like that.

“It’s hard for candidates to talk about what to do with violent offenders,” said Lauren-Brooke Eisen, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School. “It scares voters.”

But until candidates confront the issue of changing policy toward violent criminals, she said, they are just tinkering.

The Brennan Center last month rolled out a blueprint that White House contenders could use. It focuses on reversing parts of the federal crime bill signed by Bill Clinton in 1994 that fueled the prisons building boom with billions of dollars in federal funding.

The Center’s “Reverse Crime Bill” would send billions of dollars to states that substantially reduce their prison populations while keeping crime rates down.

“If you are really serious about reducing these numbers, you need to have bold proposals,” said Eisen.

So far, there have been no takers on the campaign trail.

For more on Campaign 2016, follow @evanhalper

ALSO

Rubio faces pressure from all sides over his views on immigration

Three contests in one: Your guide to the Iowa Republican caucuses

Why Iowa clings to the top of the campaign calendar, despite a spotty record of picking candidates

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.