This deaf football team was famous for losing — until something changed

Book Review

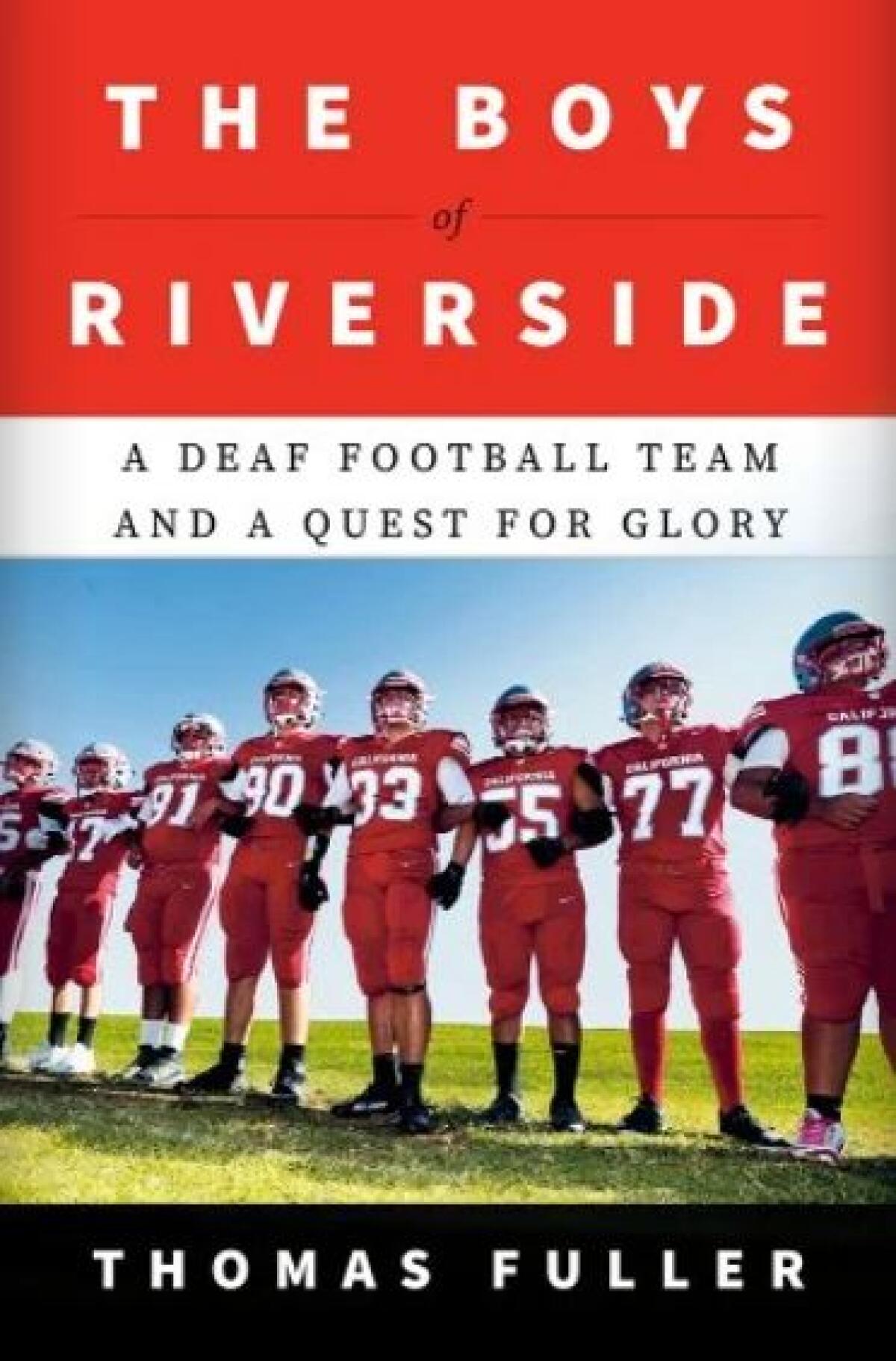

The Boys of Riverside: A Deaf Football Team and a Quest for Glory

By Thomas Fuller

Doubleday: 256 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

It’s an inspiring story to begin with: The football team of Riverside’s California School for the Deaf had slogged through 51 losing seasons, and in nearly a dozen of those they lost every game. But then came 2021, when everything turned around — and journalist Thomas Fuller learned of their story. It “pulled me in like metal to a magnet,” he writes in his new book, “The Boys of Riverside.” Fuller follows two winning seasons for the Cubs, recounted in narrative nonfiction at its finest, filled with drama, detail and action.

Late in the fall of 2021, the school wrote to Fuller — a reporter for the New York Times based in the Bay Area — to tout the team’s unexpected winning season: The Cubs were in the playoffs for the first time in history. The email was sent in hopes of garnering donations for new bleachers, but that wasn’t what interested Fuller. The larger story of the team was irresistible.

He took a leave of absence from the newspaper, moved to Riverside and embedded himself with the Cubs.

Radical! Risky! But really the only way to fully tell the story.

“The Boys of Riverside” is divided roughly into two parts — the 2021 season, which Fuller joined late that fall, and the 2022 season, which he observed every minute of and retells with enthusiasm.

Perhaps because Fuller came to the 2021 season so late, the first half of the book is less vivid than the second. We meet some of the players, but only in a cursory way. The book is front-loaded with background and history — necessary information that could have been doled out in smaller chunks throughout the book.

But be patient. The story opens up when the 2022 season begins, and it never slows down.

Nearly half of the Riverside school’s 51 students were on the football team. They played in an eight-man division rather than the more traditional 11-man, but “smaller … does not mean less athletic,” Fuller writes. And to be sure, these kids are tough: One player breaks his leg during a game and later shops Amazon for a brace so he can rejoin the team. Another breaks his ankle but finishes the game. A third does his best to play even though he is ill with walking pneumonia. “He looked like a ghost, his sunken eyes rimmed in black circles, his bony face more gaunt than usual,” Fuller writes. “He was not his jovial self. But he had greeted his family that morning with a mantra. ‘I’m playing! I’m playing! I’m playing!’”

So what made the 2021 team so special? Fuller tries to answer the question, but it’s not quantifiable. “Success in sports almost always involves more than just raw athletic talent,” he writes. “There is another crucial intangible; the mechanics and the mysteries of successful teamwork.”

The cohesiveness of the team stems partly from the players’ deafness. Being unable to hear doesn’t put them at a disadvantage; in many ways, Fuller comes to understand, being deaf is an advantage on the field. The players pay intense attention to their coach and to one another, relying on visual rather than verbal cues. (They are never penalized for being offside, for instance, because they don’t move until the ball does.) They aren’t distracted by cheering crowds, trash talk or announcers. And when they huddle or confer, they can hide their intentions from opposing teams, who presumably don’t know American Sign Language.

The Riverside players come from many countries and cultures (Mexican, Romanian, Ethiopian and Native, to name a few); economic backgrounds (one lives in a car parked in the Target lot); and experiences. Several of the players began their football careers at mainstream schools where they were relegated to minor positions on the team because communication was challenging. But at Riverside, they blossomed.

“In reporting the book, I came to see the Cubs as a flesh-and-blood realization of the American dream,” Fuller writes.

The action builds in the last third of the book when the Cubs make the playoffs again, and the last several chapters are game stories, told almost minute-by-minute. Fuller keeps the chapters short and dramatic, the pacing quick, the sentences tight. He does not hint at the outcome but lets the story unfold.

What is the best way for this book to end? If the Cubs lose, will the book lack meaning? If they win, will it be a feel-good cliché?

Fuller shakes off his slow beginning like a running back might shake off an attempted tackle and races into the end zone with gusto.

Laurie Hertzel teaches in the low-residency MFA program in narrative nonfiction at the University of Georgia.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.