Opinion: Why next week’s Biden-Trump faceoff is so novel — and what it means for future presidential debates

Next week’s debate between Joe Biden and Donald Trump will be novel for many reasons. It will be the first debate between a current and a former U.S. president. It will be the first featuring a convicted felon. It will be the first conducted before either major party has formally picked a nominee. But perhaps most importantly, it harks to an earlier time in presidential campaign politics when debates were neither typical nor expected, and when they occurred, they did so to serve specific needs of the candidates, rather than as a form of public service.

We’ve come to expect presidential debates in a pretty specific and consistent format — three faceoffs between the candidates (plus one between the vice presidential candidates) in September and October, with a pretty neutral and dispassionate moderator and a stone-quiet audience. There’s a fairly high threshold for third-party candidates to be included, and only one campaign — Ross Perot’s in 1992 — ever qualified. These were the rules set up by the nonpartisan Commission on Presidential Debates back in 1988, and both major parties have generally acceded to them. As a result, over nearly four decades, debates have become a valued tradition, seen as serving an important public function of informing voters and providing an example of civil discourse for democracies around the globe.

Frank Fahrenkopf, who helped found the Commission on Presidential Debates, has concerns about how Biden and Trump are sidestepping the process this election.

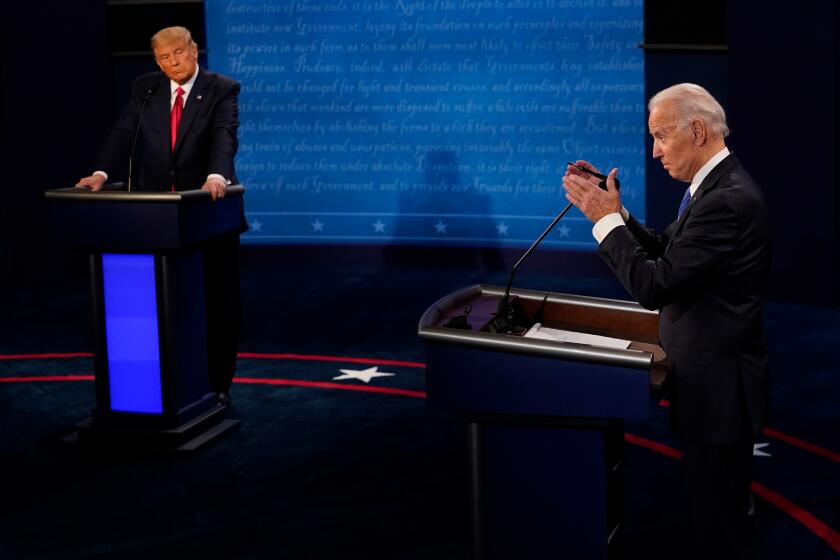

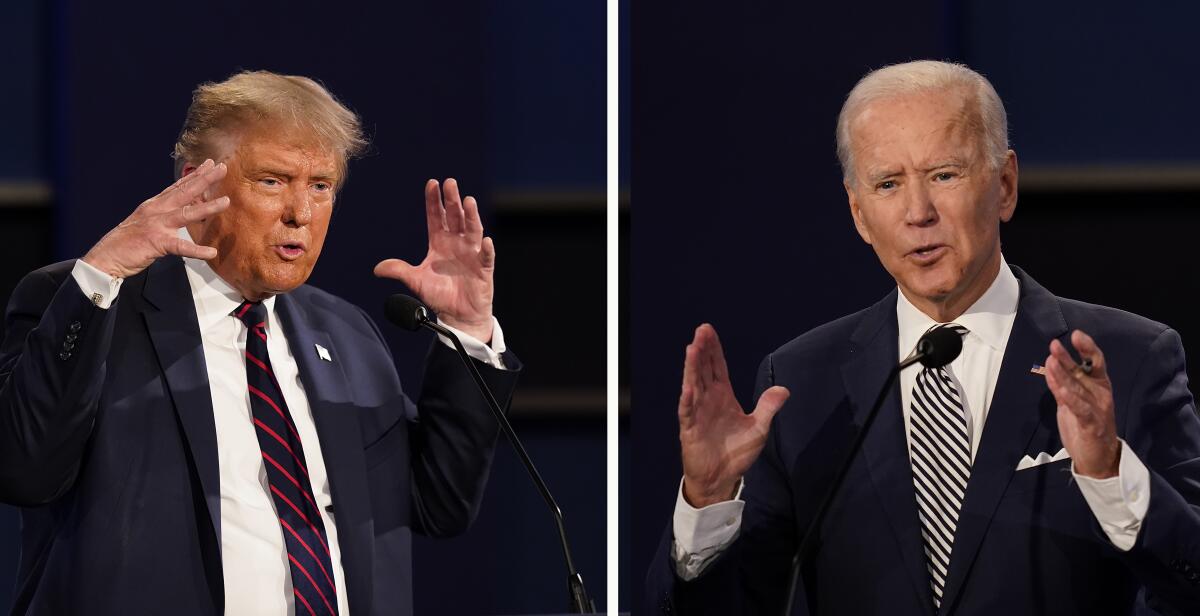

Yet the tradition frayed in 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic and some unhinged behavior by Trump — veteran moderator Chris Wallace rued that he had lost control of the first debate. And Trump and Republicans signaled pretty early in the 2024 cycle that they had no intention of adhering to the rules set out by the commission.

In its heyday, the Commission on Presidential Debates represented the institutionalization of a campaign tool, which is all well and good, but certainly not required. In other circumstances, debates are neither obligatory nor inevitable.

The reality is that any direct engagement between campaigns — whether a military battle or a candidate debate — carries risk. A candidate with a large lead has little reason to jeopardize it, which is why Trump didn’t appear at any of the Republican primary debates for this year’s election. Absent a commission-like institution, the only time a debate is likely to happen is when both sides view the risks as acceptable and the potential benefits worthwhile.

And this is a good way to think about past presidential debates. Dwight Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson could have held a televised debate in 1952 or 1956, but Eisenhower was well ahead in both contests and a bit awkward on camera. A debate presented only risks for him. Similarly, there was no real reason for Lyndon B. Johnson to debate Barry Goldwater in 1964 or for Richard Nixon to debate George McGovern in 1972; why jeopardize a lead?

The first televised presidential debate was between Nixon and John F. Kennedy in 1960, and it seemed like a good gamble for both campaigns. Both candidates were articulate, well-informed and sharp on their feet, and the election appeared to be a close one. Both had reason to believe that a debate could give them just the edge they needed to win the contest. The general belief that Nixon had looked bad on TV and that this might have cost him the election is probably at least part of the reason he had no interest in debating when he ran again in 1968.

The pre-Commission on Presidential Debates world is actually a lot like primary debates within parties, which are traditionally less formal. Sometimes news organizations set up those debates, inviting whichever candidates interested them. Sometimes they were created by just two or three candidates and excluded many others, such as when Ronald Reagan challenged George H.W. Bush to a one-on-one debate, ignoring other candidates, shortly before the 1980 New Hampshire primary. On occasion, we’ve even seen cross-party debates during primary season, as happened between Reagan and Robert F. Kennedy in 1967 or between Ron DeSantis and Gavin Newsom last year.

Column: Trump and Biden both think they can land a knockout in the debates. They can’t both be right

President Biden and Donald Trump both think they can win debates, and the 2024 election, by spotlighting each other’s flaws. They can’t both be right.

But regardless of what happens in next week’s debate, Biden proposed it for strategic campaign purposes. For one thing, by limiting the debate to just him and Trump, and by going around the commission, Biden may well have avoided Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s participation, which could have elevated the independent candidate’s stature and taken votes away from the president. Biden might well be hoping for a repeat of his State of the Union address in March, where he benefited from a strong performance following low expectations and effectively silenced some critics.

Biden’s team also insisted on no in-person audience and a neutral moderator who could shut off the microphone if a candidate goes over his allotted time. As Commission on Presidential Debates co-chair Frank J. Fahrenkopf Jr. has said, the president proposed terms highly favorable to him — perhaps more favorable than a commission-brokered debate would have been — and Trump rushed to accept those terms based on his belief that he could crush Biden one on one.

Presidents seeking reelection often under-perform in their first debate (think about Barack Obama in 2012 or George W. Bush in 2004, for example), at least in part because of overconfidence and having rarely faced direct questioning in the Oval Office. But both Biden and Trump are vulnerable to this in next week’s debate.

What’s important to remember is that presidential debates are no longer an automatic feature of the campaign environment. These candidates are debating because each of them sees this not as an obligation, but rather something that’s in their campaign’s own best interests. And they each recognize that this election could go either way.

Seth Masket is a professor of political science and director of the Center on American Politics at the University of Denver.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.