Column: Here’s how antiabortion absolutists plan to drag California back to the 19th century

In his entertaining 2019 book, “How to Become a Federal Criminal,” the criminal defense attorney Mike Chase offers dozens of examples of inane or outdated laws that somehow have remained in force over the decades, at least technically.

For instance, did you know that unless you are an actor playing a postal worker, it is a federal crime to dress up as a mail carrier? Or to paint your vehicle to look like a postal truck? It’s also a federal crime to reuse a postage stamp. Or clog a toilet in a national forest.

And the problem of so-called zombie laws isn’t just a federal one. States also have outdated laws. Rarely do their dumb prohibitions rise from the dead to wreak havoc on our lives.

But it’s happening now with a vengeance.

And we have our current ultraconservative, ultrareligious U.S. Supreme Court majority to thank for this dispiriting state of affairs.

In 2022, the new-but-definitely-not-improved Supreme Court overturned nearly 50 years of reproductive rights in its disastrous 2022 Dobbs ruling, enabling the resuscitation of laws and court decisions that would strip Americans of all kinds of reproductive rights, including possibly, as we’ve recently seen, the right to conceive children outside the uterus.

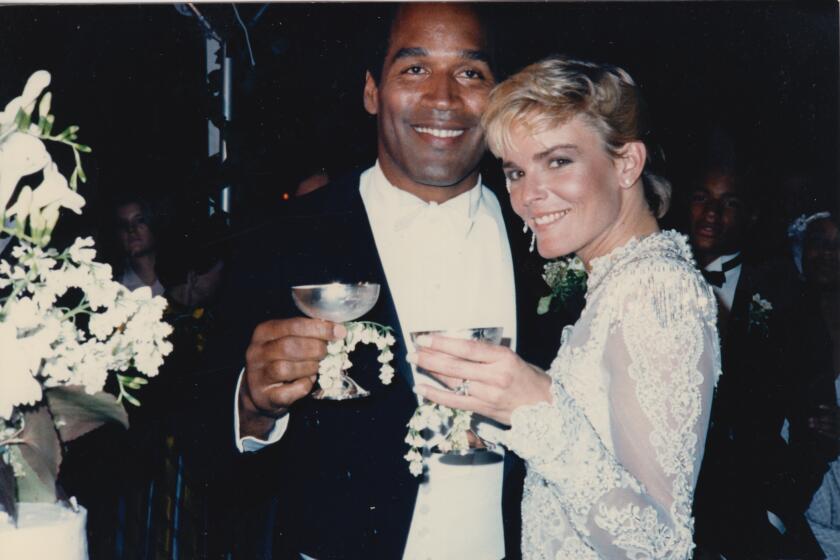

Her death proved that domestic violence can happen to anyone, and showed how little protection the police and society provided against O.J. Simpson’s abuse.

As never before, women in this country are being traumatized by retrograde forces determined to impose their specific religious views on everyone else. The goal, as always, is to force women to bear children they don’t wish to have by elevating the rights of embryos and fetuses above those of living, breathing adult human beings.

Exhibit A, of course, is the 19th century, long-dormant Arizona antiabortion law, which was revived recently by that state’s Supreme Court. The law, which outlaws abortion even in the case of rape or incest, was enacted in 1864. It became moot in 1973, but now, the federal right to abortion, as they say, is no longer operative.

Earlier this month, the Republican-dominated Arizona House refused to even consider the question of whether to overturn the state’s antiquated law, prompting cries of “Shame!” from Democrats on the floor. Last week, however, two Republicans joined Democrats in the Arizona Senate to vote to bring the proposed repeal to a vote; the House is still blocking it.

“Radical legislators protected a Civil War-era total abortion ban that jails doctors, strips women of our bodily autonomy and puts our lives at risk,” said Arizona’s Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs.

Hypocrisy alone explains South Carolina Rep. Nancy Mace’s disingenuous performance in support of the former president.

Which brings us to the Comstock Act, an 1873 federal law that banned anything related to contraception or abortion (or pornography or even love letters that described sex acts) from being transported through the U.S. mails. It came as no surprise to me that Mike Chase begins his compendium of silly federal laws with a mention of this law.

Currently, the Supreme Court is considering whether the Food and Drug Administration overstepped its authority by allowing abortion medications to be sent through the mail. The drug at issue, mifepristone, is part of a two-drug regimen that is not only extremely safe but accounts for more than half of all abortions in America.

The man who inspired the law, Anthony Comstock, was born in 1844. He was a crusading Christian moralist of the fire-and-brimstone variety who fought on the Union side during the Civil War. After the war, he moved to New York City and was appalled by what he saw: prostitution, pornography, advertisements for contraception and abortifacients, which he believed promoted lust and lewdness.

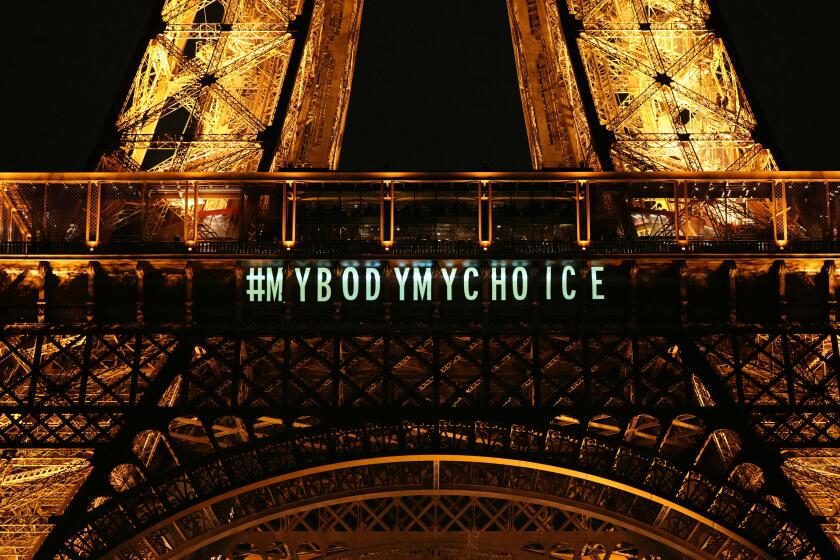

Fearing that a future government could do what the U.S. Supreme Court did — reverse the right to abortion — France champions women’s rights.

He founded the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, which functioned as a kind of morality police. The society, which finally bit the dust in 1950, opposed Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger’s efforts to promote birth control, and also, not incidentally, successfully fought to ban James Joyce’s masterpiece “Ulysses,” which it considered obscene.

So how are abortion foes trying to breathe new life into the Comstock Act today?

In 2021, in the midst of the pandemic, the FDA loosened restrictions on abortion medications and declared that they could be sent to patients by mail, instead of requiring them to obtain them in person. The agency’s mifepristone approval and its delivery mechanism, said a group of physicians who oppose abortion, went beyond the FDA’s authority. The Supreme Court is not reviewing the claim that the mailed drugs violate the Comstock Act, but the law is hovering in the background.

Even if the Supreme Court rejects the argument that the FDA should not have loosened its restrictions on mifepristone, which would wreak havoc on drug companies, it’s quite possible that a new administration hostile to abortion rights could find a way to enforce the Comstock Act anyway.

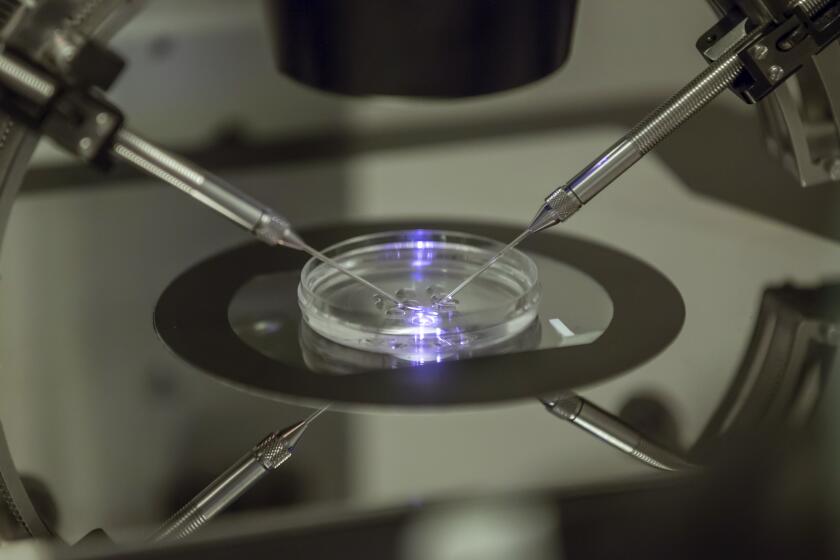

Fetal personhood laws and IVF don’t mix. Advanced fertility treatments can’t be squared with the notion that embryos are people.

“That could effectively make abortion impossible to access even in places like Minnesota, which has affirmatively protected a woman’s right to choose by passing reproductive freedom laws,” wrote Democratic U.S. Sen. Tina Smith of Minnesota recently in the New York Times. California could be vulnerable as well.

If a president were willing to reanimate the Comstock Act, some have speculated, it could be used not just to outlaw abortion, but to ban birth control, condoms and even sex toys in the mail. Do not for one moment believe that is not the goal of some of the fiercest antiabortion advocates.

What is the opposite of back to the future?

Forward to the past?

Seems to be where we are heading these days.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.