How people of color carry the burden of untold stories

Book Review

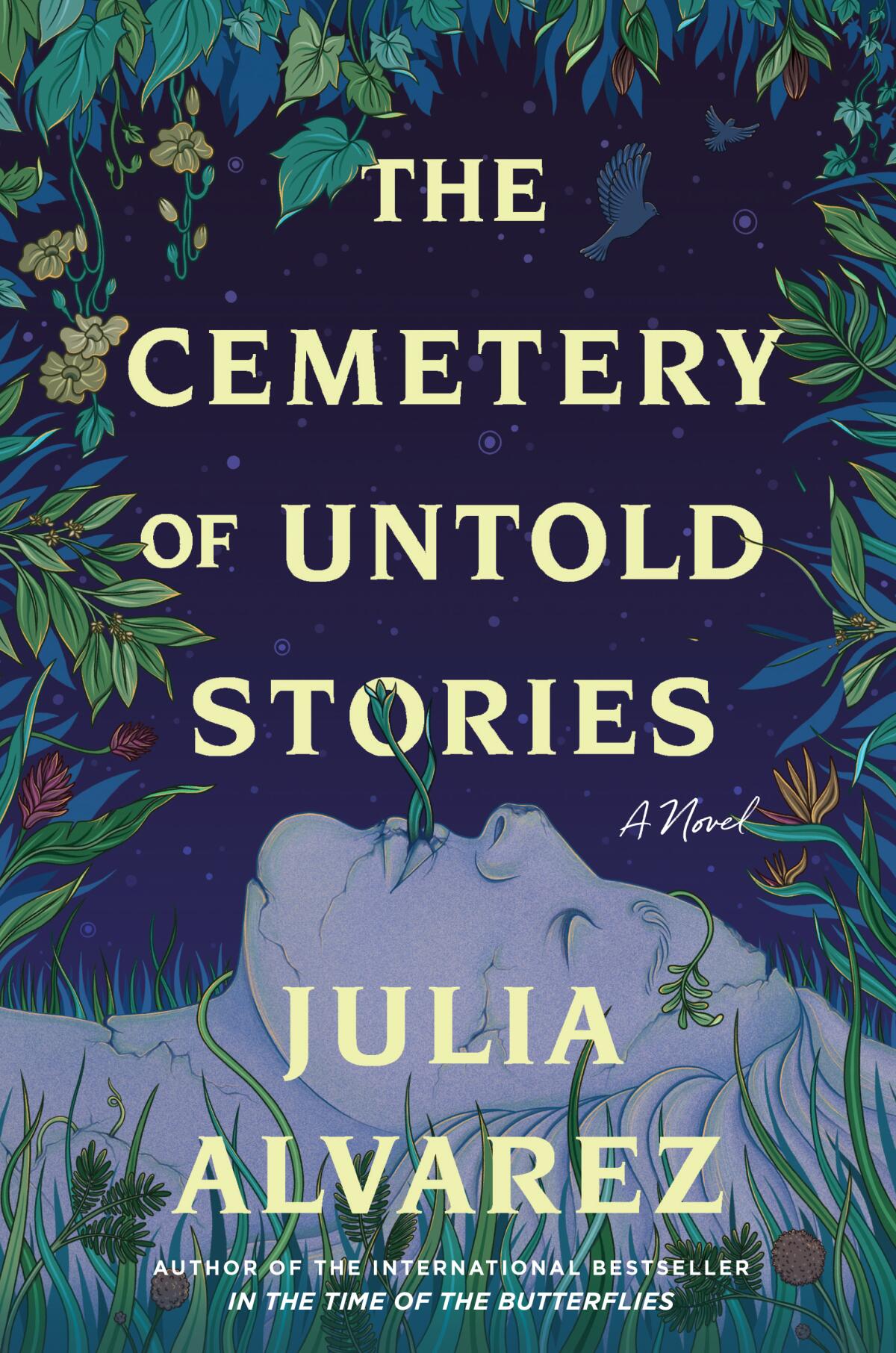

The Cemetery of Untold Stories

By Julia Alvarez

Algonquin Books: 256 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

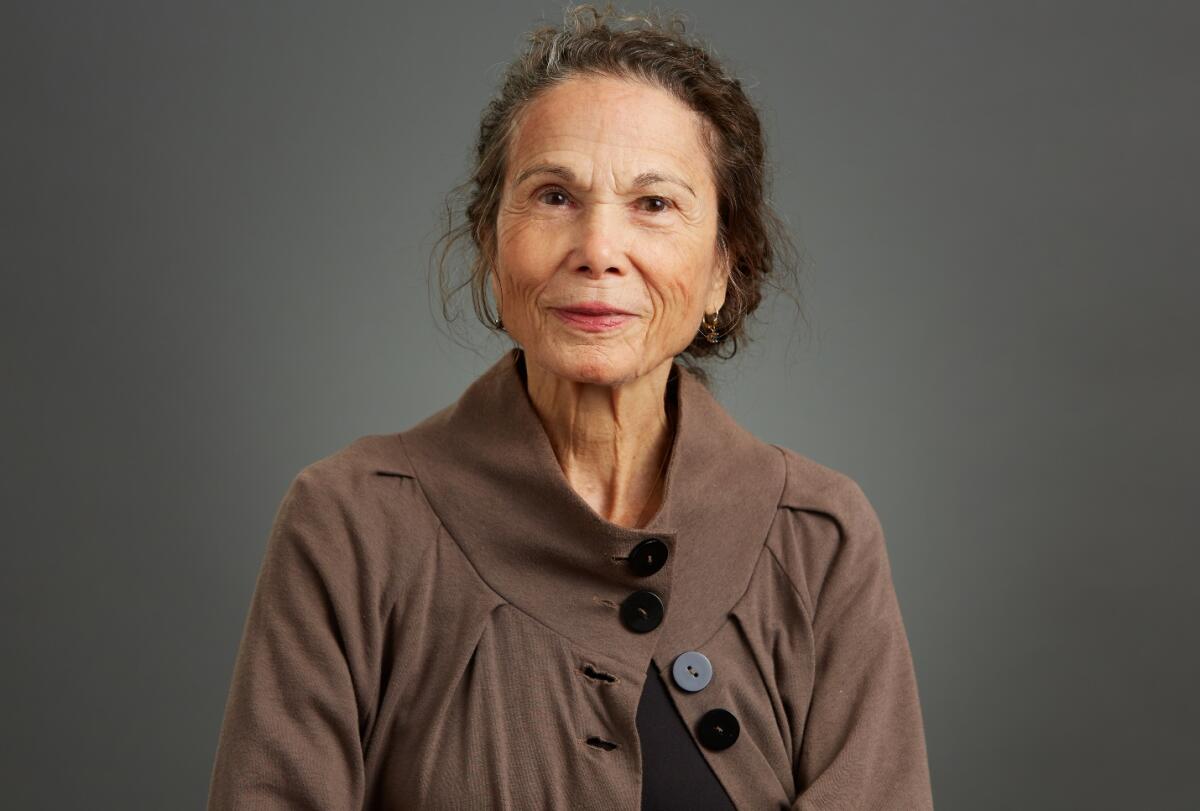

The publishing world has been largely unfriendly to writers of color, in spite of superficial efforts to make change. We know this from the last decade of studies, as well as too many anecdotes of oblivious exclusion, racism and stereotyping to count. Julia Alvarez’s warm and graceful latest title, “The Cemetery of Untold Stories,” her seventh adult work of fiction, circles around writers and stories that don’t make it to the books readers hold in their hands, however spectacular they may be.

In the novel’s clever frame narrative, Alma, a racially mixed Dominican American writer, doggedly tries to gain recognition for her fiction. Alma receives advice from a mentor, a woman who’s the same age as Alma but is a more successful, pioneering author. At a reading for the mentor’s book, a woman notes that it’s difficult to understand the dialogue in the book and asks whether she ever considers her audience. The mentor retorts that she doesn’t write for white people, taking a stand “before people were saying such things.” Despite a glorious career and an uncompromising attitude, the mentor still grieves that she hasn’t been able to tell all the stories she carries with her.

At the heart of Alvarez’s novel is an exploration of how authors’ untold stories accumulate and fester. The author Elizabeth McCracken astutely wrote in “The Hero of This Book” that “an unpublished book is an ungrounded wire.” In Alvarez’s opening pages, she uncovers an added burden of trying to publish the stories and histories of people of color, and the writerly despair of feeling those stories are lost forever upon death.

The mentor’s troubles multiply beyond an obsession with the story she can’t write to feeling that she’s being watched and chased by the feds, and distrusting the motives of those who court her because she is a literary celebrity. Alma doubts her mentor’s conspiratorial claims, as the mentor “seemed to treat her life like drafts of a novel. This plot isn’t working. Okay, no problem. Let’s take out the marriage and rearrange the sequence, see what happens. Some troubling confusion between art and life.”

Increasingly unhinged, the mentor insists Alma write down an untold story that has long possessed her. But when Alma refuses and tells the mentor it’s her job to write it, her mentor says bitterly, “I guess you haven’t heard the news that none of us is getting out of here alive.” But as her mentor’s star falls, Alma’s own successes build around her pen name, Scheherazade, after “One Thousand and One Nights.” Alma concludes that it was “that novel she could neither write nor put aside” that killed the mentor.

Death, the novel realizes, is a particularly powerful engine for storytelling. It catalyzes Alma, as she, too, ages and faces mortality. Like her lost friend, she retreats from the public eye, stops writing and publishing and grows increasingly aware of all she hasn’t been able to express. Here the novel takes a turn toward the magical, asking: Are buried stories truly dead?

When her father dies, Alma surprises her sisters by returning to the Dominican Republic to build the eponymous cemetery of untold stories on an inherited plot of land. She burns unfinished manuscripts before interring the ashes. Alma befriends an artist, Brava, who sculpts the graves’ markers. The only way visitors can enter this cemetery is by telling a story — not a mere accounting of facts — into a black box by the gate.

First to enter is Filomena, an unmarried, illiterate and humble caretaker. She gains access when she relates the gossipy story of what ruptured her relationship with her sister. But once Filomena enters the cemetery, she starts hearing unearthly voices that others can’t hear by the gravesides. These voices tell stories from Alma’s unfinished, burned manuscripts about Bienvenida Inocencia Ricardo, the forgotten, exiled first wife of Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, and Alma’s father, a doctor and dissident who fled the regime. We are whisked into the tales of love and betrayal within this frame; the voices make use of the oral tradition implied by Alma’s pseudonym and unspool a series of tales for Filomena, and for us.

Brava, the artist friend of Alma who sculpts statues and markers for the cemetery, offers a foil to Alma’s perspective that publishing is essential and that if a story is not written and published “it’ll die with its teller.” To support her counterclaim to that, Brava points to the tales Alma received from her mother and grandmother, which were “beloved on a cellular level, long before Alma ever wrote them down.”

A dream cloud of inset homespun oral tales forms, and these charming narratives whose connection is initially uncertain produce an impassioned telenovela about love, betrayal and the Dominican women who survive and find happiness despite patriarchy. The stories fuse and collapse on one another, until surprisingly, they leap out of their frame and enrich it.

Alvarez paints her characters with an unerring eye for their quirks of personality and deft humor. Her fine sense of the timeless emotional concerns faced by women trying to withstand male-dominated structures yield not only a riveting story, but also what feels like family portraits. History is not simply dusty facts, the novel suggests, in keeping with the ethos behind Alvarez’s earlier historiographic metafiction “In the Time of the Butterflies.” Rather, history lives on in the stories that intimates, and even strangers, share.

While the overall effect is mystical, the novel never loses its grip on realistic, down-to-earth detail. At one point Alma is described as having so many stories that her head “gets stuffed, like a nose when you have a bad cold.” An overabundance of stories, it’s suggested with this image, can be a kind of congestion, perhaps even painful, when they can’t be released into the world.

But if the book starts with a shrewd awareness of contemporary debates about diversity in publishing and an understanding of the toll that unexpressed stories take on writers, the frame morphs these debates into a bigger conversation about death and what lives on past us. In the richness of Alvarez’s book, stories may die, but they can also be resurrected and passed along again. “The Cemetery of Untold Stories” proves to be an imaginative celebration of living, oral traditions, and our capacity even outside the gates of publishing, to bring our stories of the past into the future.

Anita Felicelli is a novelist and critic who served on the board of the National Book Critics Circle from 2021-2024.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.