Opinion: Sheryl Swoopes is right: Black people can’t be racist

WNBA legend Sheryl Swoopes has come under an avalanche of criticism for saying that Black people can’t be racist. Last month Swoopes questioned the ability of University of Iowa women’s basketball player Caitlin Clark, who is white, to break the Division I scoring record. Her remarks, some of which she has walked back and apologized for, caused a fuss on social media, where some users accused her of racism. Swoopes responded to the accusations in part by commenting that Black people can’t be racist, causing even more backlash. But Swoopes is right. Black people can’t be racist, at least not according to the most useful definition of racism, given by a group of mainly white legislators in 1968.

This group was formed in 1968 after urban Black communities throughout the 1960s erupted in racial unrest, primarily over a pattern of police abuse and killing of young Black men. An uprising in Harlem occurred in the summer of 1964 over the police shooting death of 15-year-old James Powell. Watts went aflame in the summer of 1965 after 21-year-old Marquette Frye was beaten by police. Two years later came the “Long, Hot Summer of 1967,” which saw racial uprisings in more than 150 cities, including Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Minneapolis and Detroit.

Caitlin Clark becomes the all-time leading scorer in college basketball, breaking Pete Maravich’s record in Iowa’s win over Ohio State.

In the early morning of July 23, 1967, Detroit police raided an unlicensed, after-hours club in a mostly Black part of the city. The people inside were celebrating the return of local Black veterans from the Vietnam War. All of the patrons were arrested, and simmering racial tensions in Detroit exploded into a full-scale, bloody battle between police and Detroit’s Black community. The rioting lasted five days and resulted in 43 deaths, 33 of which were Black people, most of whom were shot and killed by police officers, but also by members of the National Guard, store owners, security guards and a U.S. Army paratrooper.

President Lyndon B. Johnson had had enough. While the Detroit uprising was still underway, he impaneled the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, also known as the Kerner Commission, to investigate this civil unrest. Johnson charged the commission to determine “What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?”

The 11-member commission, with Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner serving as its chairman, had two Black members, Edward Brooke, then a U.S. senator from Massachusetts, and Roy Wilkins, the head of the NAACP. The group returned findings that did not please Johnson, or many others. Instead of finding that outside agitators or troublemakers instigated these uprisings, the commission squarely pinned the blame on white racism. “White racism is essentially responsible for the explosive mixture which has been accumulating in our cities since the end of World War II,” the commission said. But the Kerner Commission did not stop there. It went on to offer a clear and extremely useful definition of racism. Racism was not simple hatred or prejudice based on skin color. Racism occurred when power was added to prejudice — the power to affect someone’s life physically, economically, educationally, politically or otherwise.

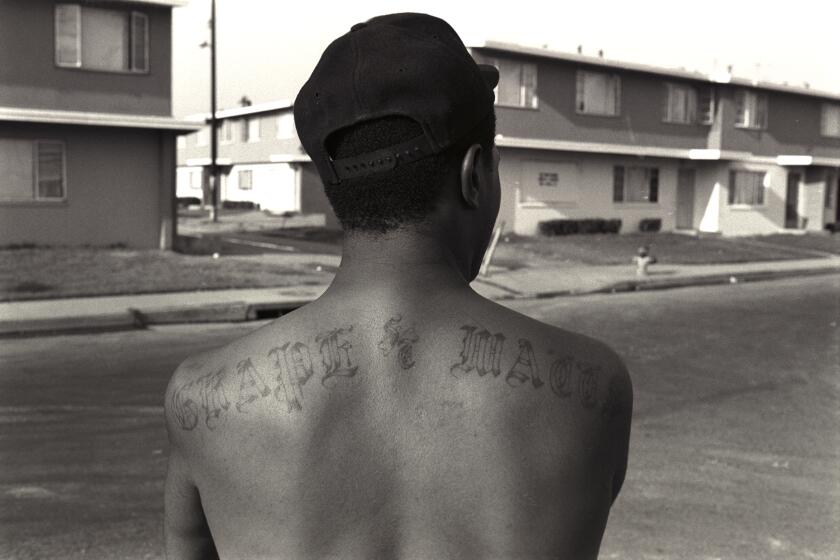

Days before the 1992 L.A. uprising, Crips and Bloods took a stand for peace.

Black or white, anyone can be prejudiced. I might not like you because of your skin color, and that makes me prejudiced. But it doesn’t automatically make me racist unless I also have the power to impact your life because of my prejudice. There are few, if any, areas of American life where Blacks hold such power. Thus, Sheryl Swoopes was correct. Blacks can’t be racist — but that doesn’t mean they can’t be prejudiced. They can.

This definition of racism opens the door to an intelligent and important conversation about the power gap between Blacks and whites. One that makes a distinction between racism and prejudice. Police brutality, overwhelmingly white-on-Black violence, is an example of racism enacted physically. Redlining, where Blacks cannot buy homes or receive loans in certain areas, is a form of economic racism. Preventing the teaching of Black history is a form of educational racism. Making it harder for Black people to vote is a form of political racism. A Black woman disparaging the abilities and career choices of a white female basketball player may be prejudiced, but it does not rise to the level of racism as defined by the Kerner Commission.

If we don’t talk about race in this country, all we will do is fight over it, often with deadly consequences. Today, there are too many examples of racism where violence, collective punishment and genocide pass as alternatives to dialogues.

And, if we are going to talk about race, a common starting point is necessary, and a decent definition of racism is as good as any. By saying Blacks can’t be racist, Sheryl Swoopes opened up a lane to the basket for a difficult, yet essential, conversation, and a path to restorative rather than retributive justice.

Clyde W. Ford’s latest book is “Of Blood and Sweat: Black Lives and the Making of White Power and Wealth.” He is a contributing writer to Opinion.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.